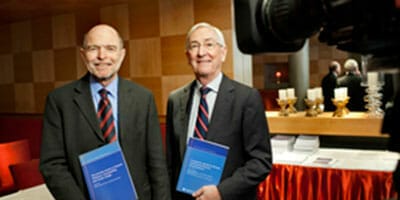

The findings from the first review of the Finnish pension system, commissioned by the Finnish Centre for Pensions, were handed down by Nicholas Barr from the London School of Economics and Keith Ambachtsheer from the Rotman International Centre for Pension Management last month.

Although Helsinki in January is far from a party Ambachtsheer and Barr reached celebrity status in presenting the findings, with their photos on the front page of the newspaper and more than 250 people showing up for a workshop.

The purpose of the evaluation was to get a forward-looking external view of the Finnish pension system from an international perspective, and to specifically get recommendations on improvement.

According to Ambachtsheer and Barr the Finnish pension system is comprehensive and robust. However, the population structure and an increasingly global economy call for further development of the system. Retirement needs to be postponed, and pension asset investments need to seek higher returns.

The first recommendation relates directly to efficiency and cost, and Ambachtsheer is of the opinion that larger pension providers, or stronger co-operation between providers, would facilitate a drop in administrative and investment costs.

Value creation

The system costs about €1.1 billion a year to operate, (with total benefit administration of about €440 million) which is roughly €107 per member and is significantly higher than the average €60 per member of an international peer group assessed by CEM Benchmarking.

However it is worth pointing out that the pension administration costs cover both pension pillar one, the universal old age pension, and pillar two, employment based pensions. This is unusual compared to other countries.

Nevertheless, Ambachtsheer says that a value creation/cost reduction target of €400 million a year is not out of the question.

Further he says if €150 billion in Finnish pension assets were moved into long-horizon return-seeking investment strategies there is a potential €1.5 billion a year incremental return potential.

These two actions combined are equivalent to a potential 1 per cent gain in Finland’s GDP, the report says.

About a third of the system’s assets are invested in Finland, and Ambachtsheer says the system, and its beneficiaries, would benefit from being more global.

One way to do this is to be more cooperative with other funds around the world and syndicate investments.

“They need to think about Finland’s funds as part of a cooperative of international funds that invest all over the world,” he says.

Interestingly the Finnish pension organisations outsource a significantly smaller proportion of asset management than their international peers – around 35 per cent, compared with an average 88 per cent in the CEM database.

The report also found that the Finnish pension organisations currently spend less money on the internal investment oversight function than their international peers, and also have lower levels of compensation of senior pension executives.

What makes a sustainable system?

More broadly Ambachtsheer believes there are three tenets to a sustainable pension system.

The first is that you need as many instruments as there are goals. So for example affordability and payment certainty are two goals and so need two instruments.

Secondly, is what he calls the John Nash principle. (Nash is the Nobel Prize winning mathematician who was the subject of the movie “A Beautiful Mind”. He specialises in game theory). Ambachtsheer says that a situation has to be win/win all of the time, even in the bad times, which means if situation changes the solutions need to be dynamic.

And the third aspect is borrowed from Einstein, keep things as simple as possible but no simpler.

With regards to the pension industry, Ambachtsheer says there is a tendency to add a layer of complexity to solve the problems.