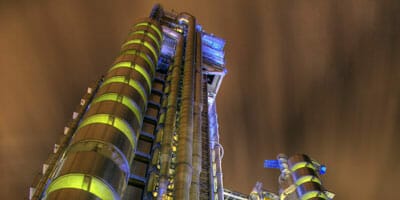

It’s difficult to ignore the clamour around infrastructure investment, the asset class of the moment. Lloyds TSB and the London Pensions Fund Authority recently joined founder members of the Pensions Infrastructure Platform, PIP, a government initiative to encourage pension funds to invest more in infrastructure. The Universities Superannuation Pension Scheme, USS, just increased its allocation to infrastructure debt with a second deal in less than six months providing long-term inflation-linked financing to a UK water company. A survey from Prequin finds that 78 per cent of UK schemes plan more infrastructure investment over the next 12 months and local authority schemes are about to be given greater freedom to invest in infrastructure at a time banks, stalwart lenders to the sector, are restrained from lending long-term by new capital requirements.

Infrastructure makes perfect sense for UK schemes struggling to manage growing liabilities and in search of new long-term, inflation-linked income on account of poor bond yields. UK schemes have lagged behind their counterparts in Canada, Australia and Europe. Foreign funds are now stoking local enthusiasm as they continue to buy prime UK assets: Canada’s £160-billion ($242-billion) Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec is close to buying a stake in the $3-billion London Array wind park off the coast of Kent in southeast England. Classic asset classes aren’t behaving properly and infrastructure is a tangible, uncorrelated investment offering capital appreciation. It may tick all the boxes but I can’t help thinking that UK pension funds aren’t going to ride to the rescue of the cash-strapped government that wants institutional investors to do the job it no longer can.

Long term, but not too long

Greenfield infrastructure is a bridge too far for most schemes. On one hand the UK’s large mature defined-contribution schemes need a cash yield from day one to meet their monthly pension obligations, which is difficult with greenfield. On the other, the flagship, job-creating type of infrastructure the UK government really wants pension funds to finance, like the proposed new rail service, High Speed 2, which will link the UK’s major cities, are just too risky.

It is eighteen years since the Queen opened the Channel Tunnel between the UK and France, but operating company Eurotunnel is only recently profitable. The project ended up costing nearly twice what it was supposed to and left a trail of bust investors in its wake. When London bid for the 2012 Olympics in 2003, the price tag was $6 billion; by 2007 that had jumped to $10.6 billion. In China it takes two years to build a railway but in the UK complicated planning laws mean it could take 20. In short, running infrastructure assets is the easy bit. The idea of contractors and project sponsors shouldering construction risk doesn’t assuage UK schemes just yet. The real risk comes in the construction phase and few have the appetite or experience to venture here.

The minefield of public opinion

Even if UK pension funds get to the post financing the construction of new infrastructure, they’ll be very choosy which assets to pick. Post-Fukushima, few UK funds will want the political hot potato of nuclear power, a no-go without government and power-price guarantees anyway. “The government needs to convince pension funds nuclear is an investible asset class,” says Marcus Ayre, head of infrastructure at First State. Hospitals, where services are being reorganised and pruned because of financial constraints, carry a health warning. Trustees may even find toll-road projects too political, unpopular in the UK because drivers believe they already pay for the roads through other taxes. Nor is equity investment into schools or prisons proving particularly attractive just yet. For sure, the bigger schemes are venturing into new areas, like the $16.6-billion Greater Manchester Pension Fund (GMPF), shifting away from pure real-estate investment to a broader infrastructure play focused on community assets, investing in social housing and the refurbishment of Manchester’s St Peter’s Square. But smaller schemes lack the size or resources to invest directly in projects that demand management similar time and oversight.

Governments and greenfield

Would government guarantees de-risk greenfield assets enough to make them less speculative? Duncan Hale, head of infrastructure research at Towers Watson, doubts it: “Guarantees aren’t a magic bullet for trustees progressing up the knowledge curve,” he says. Besides, the government is unlikely to offer guarantees anyway. How can it persuade taxpayers to subsidise infrastructure but not get the benefit from any winnings at a time when the chances of taxpayers receiving any of the $98.2 billion they pumped into Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds look more remote than ever?

It leaves most funds constrained to brownfield investment, but the market is already crowded here, with full prices paid for the safest assets with the most stable cash flows. Fixed income, investment-grade infrastructure may be the cheapest and safest way to buy into the infrastructure story, but it offers returns that may not be enough to meet schemes’ underlying liabilities. The UK’s utilities, looking for debt and equity investment, are a better bet. They’re not greenfield, they have stable cash flows and are backed by a regulatory regime that lends financial certainty to investors. Will schemes move up the risk curve with equity stakes? Some will, but most won’t because they only want low leverage and stable cash flows. It’s one of the reasons why the PIP came about in the first place – to get away from these kinds of private equity structures.

At only $1.5 billion, the PIP hasn’t had that many takers and that kind of money doesn’t go far anyway. Most UK schemes are too small to invest meaningfully in infrastructure and it’s an asset that only suits those with long-term liabilities – schemes planning a buyout won’t venture into infrastructure. The idea of savers in the community also being investors in the community is compelling, as is investing in something that you can touch, that you use everyday. UK pension funds have been involved in infrastructure investment for years but until more get properly comfy with the risk, the asset class can’t really take off.