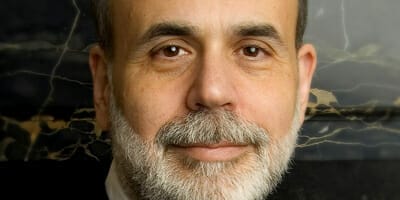

Former Governor of the US Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, says there are no foreseeable shocks to the financial system. In any case, he says, the system itself is so much more robust than it was before the crisis, that it could weather the storm. The only possible cause for concern is geopolitical risk.

Risk taking is a necessary part of the creation of new products and industries, and as long as there is risk-taking there will be various types of upset, says former US Federal Reserve chairman, Ben Bernanke.

The trick is, he says, is it so make sure that the system is sufficiently strong that if there is upset the system remains stable.

“Sub-prime mortgages were a very small asset class, but the reason the effect was so bad was because the system was so fragile and vulnerable, it was not sufficiently resilient,” he says, adding the policy decisions that followed the crisis, such as increasing bank capital, was aimed at increasing resilience.

“The garden variety crises can be tackled by fiscal and monetary tools if the financial system is robust,” he says.

“The financial system is more stable now and oversight is better. There is not much to indicate there’s major risk to the system. Growth is slow but the system is still growing and recovering. The one thing I’d put aside is geopolitical risks – which are the biggest risks. But wherever risk comes from the system is stronger so the chance of it de-stabilising is lower.”

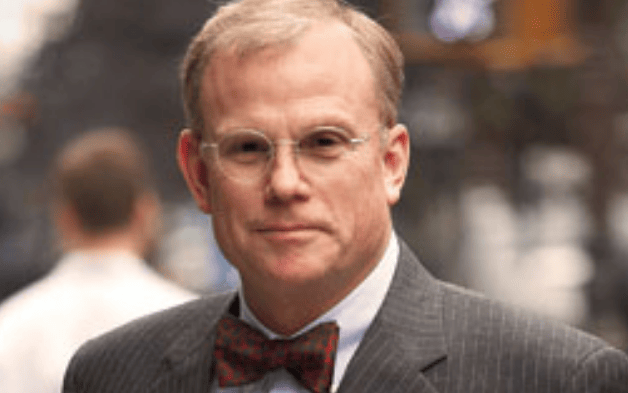

Geopolitical specialist, professor of history at Princeton University, Stephen Kotkin, says geopolitical risk, which is ubiquitous, is always triggered unexpectedly, then developments seem utterly obvious post-facto.

“Climate events or cyberattacks might seem the most obvious, but geopolitical risk is fundamentally about incompetence and mismanagement by statesmen. Russia’s pariah status, combined with its formidable spoiler state capabilities, poses one such grand opportunity for mutual miscalculation. China’s continuing advance inside the US-dominated international system poses another. In both instances it can be developments concerning small states – the Baltics or Taiwan – that set off the big catastrophes,” he says.

“We might soon learn about the question of China’s resiliency – or lack thereof – in the aftermath of a crash, which would touch all aspects of the international financial system. The unresolved impossibility of the European Union continuing in its current form may be the least of our worries.”

Bernanke who was a contemporary of Kotkin’s at Princeton, holding various faculty roles from 1985 until 2005, including as the Class of 1926 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, and the chair of the economics department, says China needs to transition to an economy driven by domestic demand.

He says slowing economic growth in China is inevitable and desirable.

“China can’t grow on the export-heavy industry and construction of the past. It needs to liberalise and the necessary transition means inevitable lower growth.”

But he also sees risks including Chinese banks “expanded credit”, and some “not very good loans”, which could create problems for the system.

Bernanke, who was speaking at the World Business Forum, said that he was “glad to say there is considerable evidence that the economy is in recovery.”

Unemployment in the US peaked at 10 per cent and is now 5.4 per cent and falling.

“Consumers in the US are in good shape. Confidence is back to normal levels, they have paid down debt and are getting their balance sheets in good shape. Consumers are more optimistic than they have been for some time. There has been a period of growth, people feel better and it’s self-fulfilling.”

While Bernanke defends the policy choices, and quantitative easing, he admits it would have been preferable to have both fiscal and monetary tools in action.

“I want to be very clear, it would have been much better if we had a better monetary and fiscal mix so we could have had recovery with high interest rates. But generally fiscal policy in the US is very contractionary so the Fed had to support the recovery and fight off the headwinds of fiscal contractions.”

But the last word is with Kotkin.

“We cannot predict the future, of course, but we can be sure that the world as we know it will not last. It never has.”

Stephen Koktin, whose recent book Stalin, vol. 1: Paradoxes of Power was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography or autobiography, will speak on geopolitical risks at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium, Chicago Booth School of Business from October 18-20.