South Africa’s 1.6 trillion rand ($131 billion) Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) has just bailed out struggling state-owned electricity monopoly Eskom with an emergency 5 billion rand ($0.4 billion) bridging loan, at the government’s behest. This has confirmed fears among South Africa’s vocal trade unions, which have worried for a while that Africa’s largest pension fund might be used to prop up ailing state-owned companies beset by poor management and performance.

Unions are also enraged that their representatives on the GEPF’s board weren’t consulted on the decision, which was executed by GEPF’s asset manager, the Public Investment Corporation (PIC).

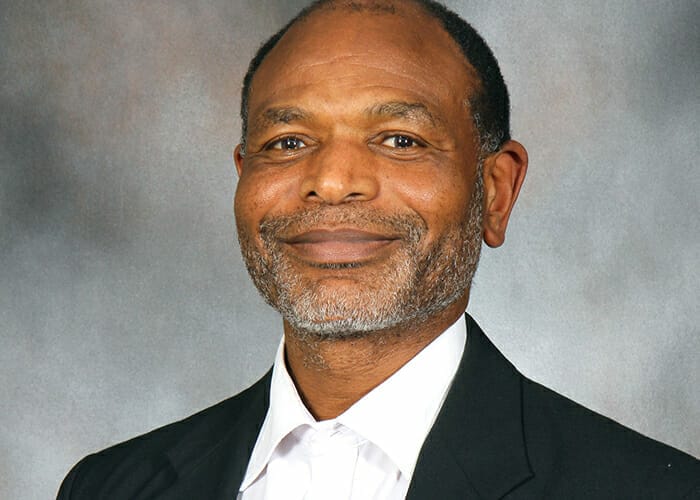

“The government did it without any consultation,” says Zwelinzima Vavi, head of the South African Federation of Trade Unions (SAFTU), whose 700,000 members include many of GEPF’s 1.7 million active members and beneficiaries. The GEPF board comprises 16 members, seven of whom are employee representatives, appointed by their respective labour unions.

Vavi says the Eskom loan is indicative of a conflict of interest within the PIC. New South African Deputy Finance Minister Sfiso Buthelezi was appointed last year to the role, which carries with it the position of PIC board chair. Vavi says Buthelezi lacks the governance track record and rigour that PIC leadership requires. Unions are now calling for an independent chair, to stop politics from keeping a grip on decision-making at the PIC.

Loan breaks GEPF’s mandate

South Africa’s biggest banks had refused to lend any more to Eskom, following allegations of corruption and poor corporate governance. The bridging loan, which ensured the company could pay February’s salaries and supplier fees, adds to the GEPF’s already large exposure to the company via a 90 billion rand ($7.5 billion) allocation to Eskom debt. The additional lending broke the GEPF’s mandate, which bars it from investing in non-investment grade assets. Eskom’s credit rating is junk status.

“We are not averse to the pension fund investing in state-owned enterprises as a matter of principle,” Vavi says. “What we are opposed to is the fact that the government has burnt all its bridges with banks and has turned around and used the PIC as a cash cow to bail out Eskom. Borrowing money from workers’ pensions in this way is a hell of a risk.”

The Eskom loan calls into question the strength of GEPF’s own governance structures at a time when the pension fund is increasingly using its influence to improve governance in investee companies.

Eskom recently put in place a new board to try to turn its fortunes around but it was the financing banks, rather than the GEPF, that pushed effectively for better governance at the utility, says Peter Draper, managing director of Tutwa Consulting.

“It is the banks that drew a line in the sand by not financing anything until governance improves,” Draper says.

GEPF principal executive officer Abel Sithole insists that “ESG is a very important consideration for the fund and is encapsulated in our investment beliefs and policies”. Sithole stresses the crucial role ESG plays in promoting the long-term value of the fund’s investments. ESG considerations are now applied across the portfolio and the fund has embarked on a process to better understand the critical ESG risks to which its holdings are exposed, and how best to mitigate them.

The price of poor governance

Beefing up corporate governance among investee companies, in which the PIC is frequently the largest single shareholder, is essential if the GEPF is to safeguard its 50 per cent of assets under management allocated to South African equity, a weighting that accounts for 13 per cent of the capitalisation of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

The pension fund’s vulnerability to poor governance was revealed at the end of last year. When furniture company Steinhoff International Holdings’ share price collapsed after it revealed accounting irregularities, the GEPF lost 0.6 per cent of the value of its entire portfolio.

GEPF owned 10 per cent of the company, a holding that made up about 1 per cent of the fund. At the time, GEPF said that, as a defined benefit fund, its members were not affected by movements in the value of individual investments.

GEPF and the PIC have now asked for board representation at Steinhoff, and are insisting on the appointment of at least two independent non-executive directors, expressing “discomfort” with the lack of board independence and a conflict of interest.

Scrutiny of GEPF’s private portfolio presents an even bigger challenge for Sithole’s ESG team and GEPF’s trustees. Unlisted equity investments total about 46 billion rand ($3 billion), the GEPF’s most recent annual report states.

Tied to corporate South Africa

The GEPF’s fortunes are intrinsically tied to corporate South Africa because its ability to diversify outside the country is limited. The pension fund’s foreign investment is capped at 4 per cent in bonds, and 5 per cent in equity, in allocations currently divided between wider African investment and developed markets. That leaves 90 per cent of the portfolio invested in South Africa, including the 50 per cent allocation to stocks, a 31 per cent allocation to domestic bonds and a 5 per cent allocation to domestic property.

“This has served the GEPF very well so far; we regularly assess our asset allocation and it is not being changed,” Sithole says.

The GEPF returned 4.3 per cent for the year ending March 2017, outperforming its strategic benchmark of 3.7 per cent. GEPF completed an asset liability study during its last actuarial valuation at the beginning of 2017.

The PIC manages all of the fund’s fixed income assets in-house and it has a socially responsible fund, Isibaya, for developmental and infrastructure investment. About three-quarters of its allocation to South African listed equities is run in-house, on a low tracking error basis. The remainder is allocated to South African private-sector managers with a range of different styles.