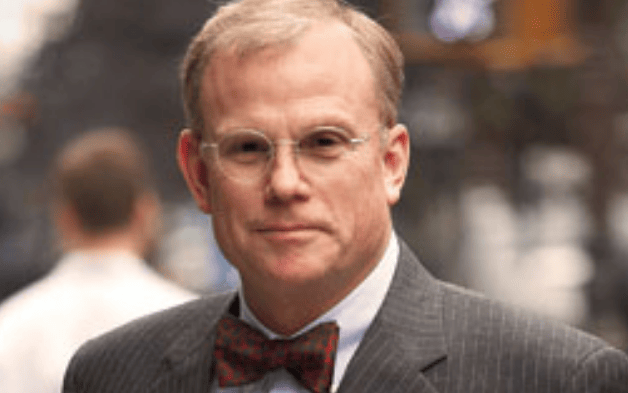

Technology has affected our ability to judge what is true and what is false. Words and images can be manipulated. Navigating through fake news, AI and algorithms to find the truth is one of the biggest challenges facing investors today, professor Stephen Kotkin has argued.

Kotkin, professor of history and international affairs at Princeton University, urged caution when describing the extent to which truth has been disrupted in today’s new epoch driven by technological innovation. It’s nothing near the extent of the falsehoods under Stalin and Hitler, he said. He also pointed out that fraud was not new, only the methods had changed. There are now apps that change our apparent gender or alter our faces to make us look younger, something he likened to old-fashioned Hollywood’s special effects.

Speaking at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at the University of Oxford, Kotkin traced today’s disruption of truth back to policy change in the US in the 1980s. he said the repeal in 1987 of the Fairness Doctrine, which had required the media to balance arguments with different voices, laid a foundation for today’s “tribal” divisions and belief that, “If it’s good for me, then it’s true. If it’s not good for me then it’s fake news.”

He said technology was also to blame, such as the rise of addictive algorithms that lead us down prescribed paths; an initial internet search invariably leads us to another, more extreme, site that will ensure our attention remains focused.

“The business model of social media is based around [the idea that] the more extreme things are, the more you will stay [tuned] to watch it,” he explained.

Investors have even more reasons to be worried. The financial data they rely on, from government policy announcements around interest rates to their own company information, is all at risk of being falsified. Financial markets will react just as quickly to fake news as to the real thing. An AI-generated market-moving speech from a politician will be impossible to differentiate from the real thing, he said.

“Imagine if this information is delivered in real time, falsely,” he said. “This is the world we are about to enter, it’s moments away.”

He asked delegates, “Who is protecting your data?”

Ways to fight it

Kotkin did offer some encouragement that the problem might not be as bad as it seemed – at least in democracies. He pointed out that although false stories spread more than true stories, false stories also diffuse more quickly. He noted that Twitter users who spread falsehoods had fewer followers and argued that the “fake stuff is shallow; it is spread more, but not as wide or as deep”.

There were also solutions to hand, he said, and listed values, technology, private capital and imagination as important counters. Fact-checking helps, although he noted that the people who consume fake news don’t look at fact-checking sites.

Stronger branding does not work as a stamp of authenticity, since it is easy to simulate brands; however, companies and organisations can use their weight as advertisers on the big platforms to effect change. When American consumer goods giant Procter & Gamble slashed its digital advertising budget, it didn’t hurt sales, he said. Investors can also engage with internet firms to get them to take their responsibilities more seriously.

But the real cure to killing off fake news begins in schools and at home, Kotkin said, with the teaching of the lesson that truth is many-sided and not universal.

“The only way to combat this is by teaching tolerance; we need it like oxygen,” he said.

Technology is the problem, but it is also the solution – primarily Blockchain or distributed ledger technology. Blockchain’s ability to store data so that it can’t be changed or altered, in a chain visible to all, is a guarantee that data is genuine.

“This way, everyone has the same record of a transaction,” Kotkin explained.

The established internet giants publishing fake news and damaging the ability to know what is true and false were fighting to preserve the status quo by snuffing out any innovation that threatened them, Kotkin said. This manifested as “buying companies, buying ideas and putting them to bed,” he explained. But he argued that an “inflection point” would come that would allow the new technologies that help solve the problem to come to the fore. He likened it to a point in the hydrocarbon sector when the cost of investment would lead to an implosion and consign fossil fuels to the past.

“This is a model of how change could happen,” he said. “When will people start fleeing from the internet? They will go somewhere else when there is somewhere else to go.”