There have been occasions over the last few decades when a new concept, investment approach or asset class has suddenly attracted interest and, within a matter of months it seems, everyone is talking about it. A fuse is lit and, in no time at all, the fire catches. So it is with impact investment – it is the 2018 topic of the year. All of a sudden, every investment conference on the block is advertising at least one session on impact investment, with mainstream managers and niche boutiques all vying for attention.

Impact investment is not the same as ESG. Nor is it responsible investment. It is also not philanthropy. Rather, it is an approach in which the investor still receives a financial return but the investments are intentionally chosen to generate a positive social or environmental impact, which is quantified and measured.

The nature of impact investments generates a natural alignment of interest with local authorities. In the UK, local authorities are familiar with many of the social and environmental challenges these investments are looking to address. Indeed, if a local authority can attract private capital to invest in residential property to house the homeless, then that should have a direct impact on the budget that authority requires to address homelessness in its county or borough.

Within the UK’s Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS), there is likely to be member interest in this type of investment, given that staff have had to deal with residents’ social and environmental issues over many decades. In addition, as a pension scheme, the LGPS can afford to take a long-term view with its investments, thus allowing its fund managers time to maximise both the financial return and the impact. Some social and environmental issues take many years to address.

Given the natural alignment of interests, it is somewhat surprising that, to date, LGPS allocations to impact investment have been relatively modest. Pensions for Purpose, a collaborative not-for-profit platform that aims to raise awareness of impact investment, lists several case studieson its website, and many of these include descriptions of the journeys by LGPS funds such as West Yorkshire, Berkshire, Merseyside, Greater Manchester and the Environment Agency in establishing an impactful investment approach. This journey typically begins with a discussion on ESG, then progresses to a debate around responsible investment, including, for example, the ‘divestment versus engagement’ debate. Eventually, impact investment is on the agenda.

The Pensions for Purpose case studies show that, for some LGPS funds, the desire is to focus on environmental impact; for others, addressing social need is more important. Some may take a global approach, while others specifically try to address a need in the county or borough in which the fund is based. There is no right or wrong answer, provided the financial risk/return characteristics on the underlying investments remain suitable for the pension fund’s strategic investment goals.

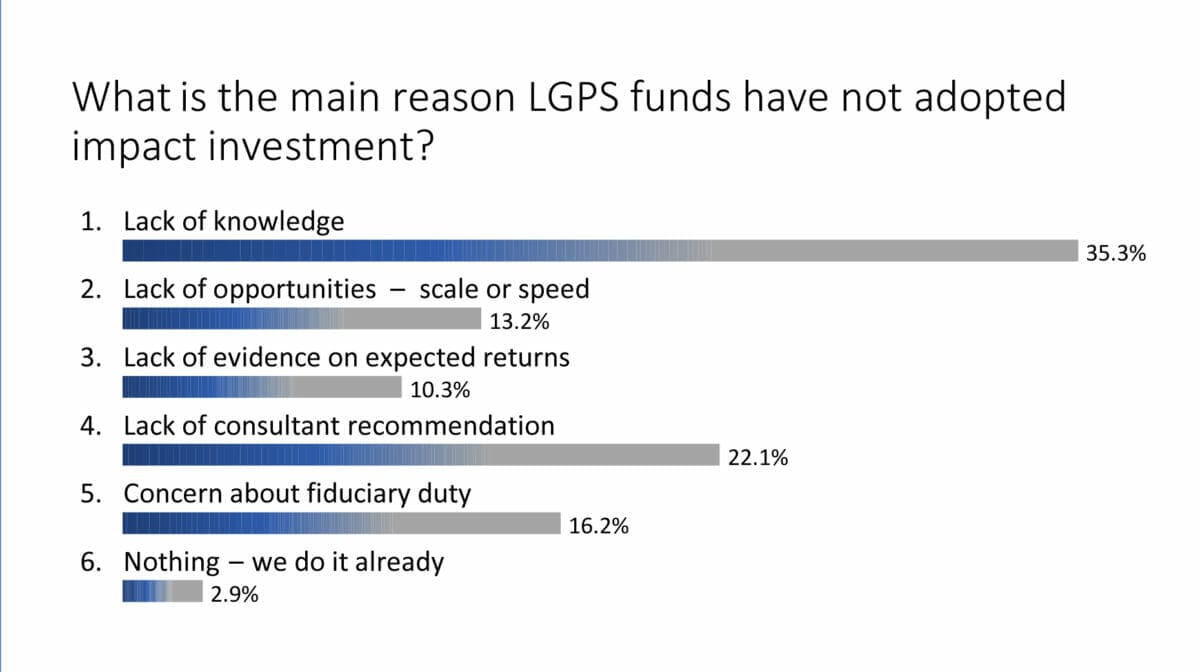

So why haven’t more LGPS funds dipped a toe in the water? This question was put to a group of delegates at a recent LAPF Strategic Investment Forum. The responses are shown in the following chart.

Source: LAPF Strategic Investment Forum

The overwhelming response was, quite simply, that it boiled down to a lack of knowledge about these investments. When analysing responses by delegate type, it became clear this was an especially common stumbling block for investment committee members; just over half of this group said they had not adopted impact investment because they lacked the knowledge to make an informed decision.

It is this stumbling block that Pensions for Purpose is looking to address. The platform has two types of members: influencers and affiliates. Influencers pay an annual fee that allows them to post impact investment-related content on the platform. Influencers include fund managers, lawyers and – soon, it’s hoped – consultants. Affiliates, on the other hand, can join for free; they include asset owners such as pension funds, foundations and charities, along with independent advisers, researchers and journalists.

The Pensions for Purpose content consists of thought-leadership pieces, blogs, case studies, press-related articles and information about impact investment events. No investment products are promoted, so it succeeds in being a genuine information platform. Most of the content on the website is publicly available but some material) is only accessible to affiliate members, at the influencer’s request.

Brunel Pension Partnership’s profile on the Pensions for Purpose website, states: “As an affiliate of Pensions for Purpose, Brunel is able to participate actively in thought-leadership discussions and enhance the general understanding of impact investment within our community and in the wider investment community. In addition, through discussion with other affiliates, including asset owners, government bodies, independent advisers and journalists, we are able to deepen our knowledge of this important topic for Brunel.”

It comes as no surprise, then, that LGPS representatives form a large portion of the affiliate membership of Pensions for Purpose. The group has a noticeable desire to learn more, evidenced by a growing number of invitations for Pensions for Purpose representatives to speak about impact investment at LGPS workshops, conferences, discussion groups and training sessions.

Pooling impact

Yet if interest in impact investment is starting at the grassroots level, what are the implications of pooling LGPS assets? Is making impact investment one step further removed from the underlying beneficiaries of the pension fund likely to help or hinder the level of impactful investment?

As always, there are pros and cons. One advantage of pooling is that it allows the member funds to join forces and invest in a more diversified impact approach. A disadvantage of investing in a fund that will directly tackle assisted living in a given borough, for example, is that the financial characteristics of that investment could potentially result in quite high specific risk (in order words, it would be exposed to property market valuations in that specific area). Yet if the member funds of a pool joined forces and invested in an opportunity that tackled, for example, disability living in the Midlands as a whole, the return profile would be much more diversified, despite the capital still being deployed in each of the member funds’ own counties.

A second advantage of pooling is that it allows specialist resources to be allocated for due diligence of funds or investments. This is a new type of investment for a pension fund, so due diligence and close monitoring are important. Yet this can be a drain on limited resources for an individual authority. Already, pools such as Brunel are developing expertise in impact investment and this is likely to spread to other pools as interest in the approach increases.

The growth of impact investing does, however, levy its own demands on pools. Pool officers are likely to be faced with the challenge of how to scale up their impact investments as their popularity increases. Several underlying investments in an impact sub-fund are likely to be in private-market funds, offered on a smaller scale than pools might be used to having elsewhere in their investments.

There are several ways to address this. First, managers in the listed space are developing their impact expertise. This will allow the pools to offer sub-funds with a mix of public and private markets, and with a spread of different impact goals. One of the concerns about this, raised by private-market managers that have been offering impact investment for decades, is that such an approach dilutes the impact. Listed managers tend to be investing with impact rather than for impact. In other words, the companies in which they are investing are still, ultimately, looking to maximise the return on shareholder capital; the positive impact being achieved is not always the primary driver for them. Unlisted managers, on the other hand, tend to be much more focused on maximising the impact from their investments and many have this embedded into their mission and values.

Second, the unlisted managers are becoming increasingly creative when considering scale. For example, can an impact process that worked in one sector now work in another? Can a regional approach be expanded into a national approach?

Ultimately, capacity constraints will probably be solvable, although it will be harder for a pool than for an individual LGPS, simply because of the larger sums of money involved.

Where to begin?

The best starting place for any pension fund considering an impactful investment strategy should be getting the trustees to re-articulate their investor beliefs. This is no mean feat and may involve soliciting member views. It is important to note that member views may well be influenced by the age profile of the pension fund. A recent survey by Barclays found that 43 per cent of investors under the age of 40 had made an impact investment, compared with just 3 per cent of those aged over 60. A pension fund with a younger age profile could get a very different response on impact investment than a pension fund of largely retired members.

Once member views are known, the trustees should be ready to discuss questions such as:

- How do we align short- and long-term goals for the fund?

- How can we best achieve a sustainable pension fund for future members?

- Do we want to become more impactful in our investments?

- How do we plan to measure the impact of our responsible/impact investment?

- Are we more concerned about environmental issues, social issues or economic issues?

- Do we want to try to solve domestic issues or global challenges?

These are not easy questions to answer but defining investor beliefs at the outset will lead to a far more straightforward exercise when it’s time to articulate a strategy for impact investment, embark on a relevant and tailored training program and direct funds towards investments that are appropriate for the strategic goals of the pension scheme.

Karen Shackleton is director of Pensions for Purpose.