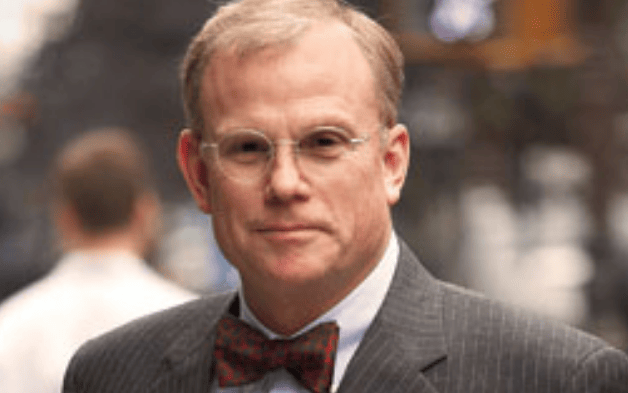

China and America’s relationship is the biggest geopolitical risk on the global landscape, said Stephen Kotkin, speaking at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Stanford University. The John P Birkelund ’52 Professor in History and International Affairs at Princeton University, and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, told delegates conflict could arise over Taiwan.

He discounted geopolitical risk on the Korean peninsula. Although it is dangerous and potentially catastrophic for the region, it doesn’t pose a systemic risk, he said. Nor, in Kotkin’s estimation, do Russia, instability in the Middle East, or Iran, which has a small army and uses proxies and militias to fight its wars.

He said the “Trump chaos” that has manifest in a denunciation of allies and breaking of key global agreements, looks very different from Obama’s policies. However, scratch beneath the surface and US President Donald Trump’s policies are not that dissimilar, he argued, because the administration is grappling with the same problems as Obama’s: the US is trying to reduce its foreign commitments, demand more of its allies, and find more common ground with its adversaries as America’s power in the world declines.

“Obama tried to do all these things, the style was different, but the substance is similar,” he said.

Kotkin drew on the Iranian and North Korean nuclear challenges to illustrate his point. Trump has rubbished Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran but has sought to cut his own nuclear deal with North Korea. Trump’s decision has enraged European allies but has been supported by other allies in the Middle East, such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, he said.

Kotkin said China’s growing military muscle was illustrated by its stake in many ports around the world. He said these ports had a “dual purpose” of commercial and military gain. China is laying down infrastructure to imitate US military bases around the world and drive a commercial story, he said. China’s activity in the South China Sea, where it has built naval bases on coral reefs amounts to a “huge military presence” in a region that used to be dominated by the US.

The professor said the clash between China’s growing power and the overstretched, declining power of the US would come to the fore in Taiwan. For decades, China’s claim over Taiwan, and Taiwan’s de facto independence, have been countered by preserving the status quo.

“We’ve been with the Taiwan problem for a long time, but it’s never blown up,” Kotkin said.

Taiwan now depends on China economically, yet economic integration has not bought political integration. Instead, the Taiwanese identifying as Taiwanese are in the majority, with opinion on the island now moving away from political integration with mainland china.

Beijing is applying pressure on Taiwan, Kotkin said, noting the increased military exercises around the island. That leaves the US with a problem because, in the event of a dispute, if the US fails to protect Taiwan it would threaten the US alliance in Asia.

“This is your systemic geopolitical risk,” Kotkin said. “This is what you should pay attention to.”

He said the current trade war was the opening phase of this wider potential conflict, which could eventually lead to portfolios getting “incinerated”.

He said one solution was to maintain the status quo, which could be possible if Taiwan made no move toward formal independence and the US didn’t encourage it to do so. He said diplomatic negotiation was also possible, with confident diplomats and without local politics driving the agenda. But he added that a war could unfold that would poison the water and air, destroy energy plants and create domestic chaos.

Kotkin said the trade war was part of a larger strategy by the US to destabilise the Chinese regime, which he said the Trump administration believed was unstable and vulnerable.

“Authoritarian regimes are brittle,” he said, noting that despite breath-taking economic innovation, the Chinese regime was afraid of its own people and didn’t act confidently.