The funded status of corporate DB pension plans has experienced unprecedented volatility in the 21stcentury. This paper examines the sources of funded status volatility seen over the past two decades and discusses how plan sponsors of DB pension plans have adapted. Numerous pension de-risking techniques are available for plan sponsors to use depending on their risk exposure and risk tolerance. It should be noted that risk management, by definition, can be a risky business and we will cover the pros and cons of several popular de-risking mechanisms.

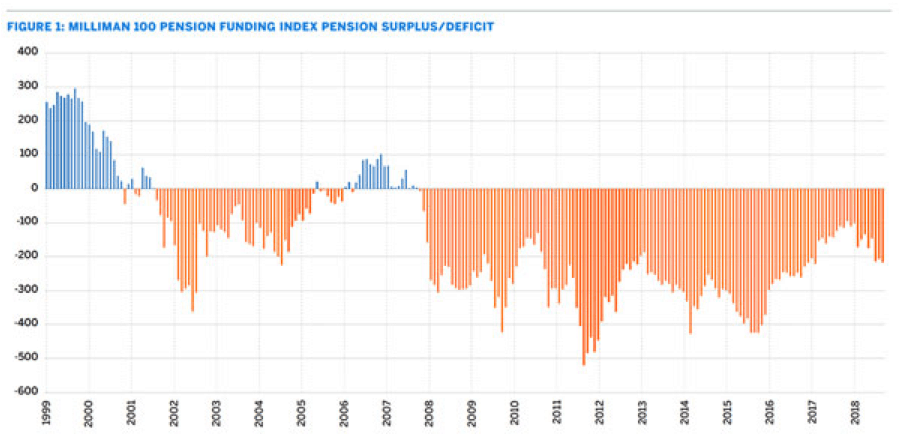

The accompanying surplus/deficit chart tells the story. It shows the history of the Milliman 100 Monthly Pension Funding Index (PFI), which measures the aggregate funded status of the 100 largest U.S. corporate DB pension plans.

The chart shows four distinct periods of surplus and deficit. When Milliman established the PFI in 1999, DB plans were generally in surplus positions and this observed surplus continued through the end of 2001. However, the Milliman 100 pension plans recorded a funded status deficit of $16 billion by early 2002, in the wake of the dot-com crash and the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The chart shows four distinct periods of surplus and deficit. When Milliman established the PFI in 1999, DB plans were generally in surplus positions and this observed surplus continued through the end of 2001. However, the Milliman 100 pension plans recorded a funded status deficit of $16 billion by early 2002, in the wake of the dot-com crash and the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

The ensuing period of deficit lasted until 2006, with the funded status deficit reaching $36 billion. An all too brief economic and funded-status recovery followed with the funded status surplus reaching $3 billion in 2008. This period of surplus was short-lived, as the Milliman 100 plans began their second distinct period of deficit positions in 2008, during the time of the worldwide global financial crisis, with the funded status deficit starting out at $7 billion. Those deficits have continued through the recession and beyond, exceeding a decade. This leads us to the current funded status deficit of $212 billion as of June 2019.

Taking a deeper dive into the liability and asset components of the balance sheet will give further insight into the funded status volatility. First, we can examine the benchmark corporate bond interest rates used to value the pension liabilities of the Milliman 100 plans. Fourteen out of the last 20 years have resulted in net decreases for the year in corporate bond interest rates. Over the past 20 years, our highest year-end discount rate of 7.70 per cent was observed at the end of 1999 while our lowest year-end discount rate stood at 3.53 per cent at the end of 2017.

Discount rates

Discount rates dropped for six consecutive years from year 2000 to 2005 inclusive. The discount rate for the Milliman 100 plans at the end of 2005 was 5.45 per cent. The next three years saw rises in discount rates, followed by years 2009 through 2012, when discount rates further plummeted, reaching 3.96 per cent by the end of 2012. Since 2012 we’ve had four further years of discount rate drops interspersed with three years of discount rate increases. In 2019 thus far, discount rates for the Milliman 100 plans have dropped 74 basis points to 3.45 per cent as of June 30, 2019.

To provide some perspective on discount rate movements and their resulting liability gains or losses, a pension plans’ duration is often calculated. The duration of liability calculation is specific to a particular plan’s expected benefit payments and the plan’s discount rate. As of June 2019, the discount rate for the Milliman 100 plans was 3.45 per cent. Under that discount rate environment, plans with short durations had a measure of roughly 12 while plans with long durations had a measure of roughly 20.

These duration measurements essentially tell us that for a swing of 100 basis points in discount rates, pension liabilities can be expected to change anywhere from 12 per cent to 20 per cent. With discount rates falling over 400 basis points over the past two decades, pension liabilities have increased over 60 per cent at a minimum, with some even doubling in present value.

With pension discount rates as measured by high-quality corporate bond interest rates having been below 5 per cent for essentially the last eight years, one wonders whether this is the new norm. While it’s not clear whether pension liabilities will ever experience consistent reductions again attributable to rising discount rates, we do have some hope coming from the other side of the balance sheet.

Asset returns

In 11 of the past 20 years, asset returns of the Milliman 100 plans have beaten return expectations. Also, in the past 20 years, the Milliman 100 plans have had only five years where negative returns were experienced. The two worst return years occurred in 2002 following the dot-com crash, where assets lost 11.5 per cent of their value, and in 2008 during the global financial crisis, where assets lost 21.2 per cent. Generally, in periods directly following those of crisis, asset returns have roared back making up for past losses.

Over the last decade, six of the last 10 years have seen the asset returns of the Milliman 100 plans exceeding their return expectations. The average annual asset return for the Milliman 100 plans over the last 10 years has been about 7.9 per cent. But this annual return hasn’t been enough to keep pace with rising liabilities during the same period due to dropping discount rates. Looking at the funded status deficit period from 2008 to 2019, cumulative asset returns have been about 82.5 per cent. However, discount rates have fallen by 335 basis points over that same period, more than offsetting investment gains as the funded status deficit worsened by $205 billion.

De-risking

How have DB pension plan sponsors survived during these times of funded status volatility? Aside from meeting minimum funding requirements and at times contributing beyond minimum requirements to put a dent in unfunded liabilities and/or build reserves, plan sponsors have been keeping a keen eye on pension risk management. Numerous pension de-risking solutions have come into play over the past 20 years and continue to be executed to help plan sponsors keep a handle on balance sheet exposures. As with any proposed solution, new risks may exist and risk reduction methods are no different. They have associated costs and some are more preferable to others, depending on a plan sponsor’s funding situation and overall risk tolerance.

The first step in a de-risking program is to understand the plan’s risk exposure. This is a matter of systematically working through the different categories of risk, which could include discount rates, investment return, participant longevity, and pension administration, to name a few. In each case, the plan sponsor needs to analyse how its plan’s specific exposure to risk impacts the balance sheet, pension expense, and cash contributions.

A second step involves determining the plan sponsor’s risk tolerance. Plan sponsors need to prioritise the risks they wish to mitigate. The appropriate de-risking solution will ultimately depend on the plan sponsor’s risk tolerance. This includes how much they are willing to pay for the risk reduction solution versus tolerating the risk internally, essentially leaving it unhedged.

A third step involves bringing a pension plan’s risk exposure to within an acceptable tolerance level as defined by the plan sponsor. Risk exposure needs to be examined on an individual company basis. On many companies’ balance sheets, the pension plan does not show up as a first-order-of-magnitude line item; thus, there may be less motivation to pursue certain de-risking strategies relative to another organization whose pension risk exposure is more dominant.

What strategy?

De-risking strategies encompass a wide spectrum of options, each having different focal points and costs. Over the past two decades, plan sponsors have executed a wide range of techniques, which have involved liability reductions, asset allocation optimization and return maximization, combined liability and asset tracking, plan size reductions, pension risk transfers, and plan terminations.

Plan liabilities can often be effectively controlled through changes to the plan design. After reviewing pay and service definitions, the plan formula, plan subsidies via optional forms of payment, and the overall benefit accrual pattern, actuaries can make recommendations to meet the sponsor’s de-risking objectives. Hybrid plans such as cash balance plans have replaced many of the traditional final average pay plans that have existed in the private sector. Variable annuity (VA) plans provide different nuances of cost sharing and benefit guarantees. Other employers dealt with rising liabilities by closing their plans to new entrants, with some going a step further by freezing accruals.

Cut equity

Plan sponsors have changed asset allocation over the past two decades, moving away from equities and more into fixed income. That’s a key signal toward investment risk reduction and overall plan de-risking. At the end of 2005, the Milliman 100 plans had asset allocations to equities of 62 per cent and fixed income allocations of 29 per cent. The most recent Milliman Pension Funding Study for corporate plans shows allocations to equities and fixed income at 31 per cent and 49 per cent, respectively. With the change in investment allocation has come an associated drop in return expectations for the Milliman 100 plans. Return expectations were as high as 9.4 per cent back in the year 2000 and have steadily decreased since then, coming down to 6.6 per cent in 2018.

LDI

Asset management strategies have also been developed to better track a pension plan’s liabilities, allowing the plan sponsor to protect and maintain a plan’s funded status. Liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies are the most well-known in this genre. LDI strategies are designed to significantly reduce the volatility of both a plan’s funded status and its contribution requirements, with the goal being to match the duration of the plan’s liabilities with that of the asset portfolio, which is generally composed of fixed income instruments.

Once fully implemented, a plan sponsor can be agnostic to changes in interest rates and investment returns as the value of the plan’s assets and liabilities would move in similar directions by design. LDI strategies may differentiate themselves by the use of derivatives. One such example may involve the use of interest rate swaps to perhaps increase the degree of interest rate risk protection. In practice it is impossible to achieve a perfect match between assets and liabilities.

Thus, it’s unlikely that plans will commit 100 per cent of their assets to an LDI strategy, especially those plans with ongoing accruals that require an equity allocation to keep pace with liability growth. Many plans have used funded status triggers to signal further asset allocation shifts into fixed income toward achieving LDI, a practice known as dynamic LDI.

Lump sum

For those plan sponsors with little to no pension risk tolerance or the relatively small subset of plans whose pension risk footprint is so large that the company is willing to pay almost any price to eliminate it, risk transfer strategies are at the heart of the solution. Two popular risk transfer strategies are lump sum windows and annuity purchases, the latter also known as pension buyouts.

While a lump sum can exist as a permanent plan design feature, many sponsors have executed lump sum windows over the past decade and there seems to be no end in sight. Recent guidance from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has opened up the possibility of lump sum offers to retired participants in addition to the usual candidates of terminated vested participants.

Offering a lump sum window or amending a plan to offer lump sums permanently are both designed to relieve the plan sponsor of future liability risk. While lump sum strategies transfer risk from the plan sponsor to the participant, annuity purchase strategies transfer risk from the plan sponsor to a third party.

Annuity purchases involve the transfer of pension assets and liabilities to an insurance company that is deemed by the plan’s fiduciaries to have a very low probability of default. Transferring liabilities to an insurance company can come at a significant cost relative to funding the plan on an ongoing basis. A plan sponsor typically uses a buy-out strategy to secure participant benefits when plan termination is on the horizon. A plan termination is essentially the ultimate third-party risk transfer strategy, and corporate plans have seen a number of plan exits over the past 20 years, more prevalent in some sectors than others.

De-risking the risk

Risk management deals with probabilities, not certainties. Therefore, it is important to understand that pension risk management strategies have their own implied risks associated with them. Sometimes, the risk can be explicit in the form of an increased cost. Other times, the risk may not reveal itself until further down the road from implementing a given strategy.

For example, lump sum window strategies can have several risks associated with them. They may include participant anti-selection, opportunity costs of plan assets leaving the plan, market interest rate movements that could affect the calculation and valuation of future lump sums, settlement accounting charges added to pension expense, and a drop in funded status and an associated increase in short-term required contributions. Other risks include an insufficient participant election rate making the cost of administering and executing the window high relative to the risk reduction achieved.

Annuity purchases also have several detractors in addition to their relatively higher cost compared with other pension de-risking strategies. Retired participant buyouts can actually add to a plan’s funded status volatility because the remaining plan liabilities will be longer duration and thus more sensitive to interest rate changes. Furthermore, for a plan seeking to fully terminate, a plan that has had a retiree buyout may sometimes not get as favorable a pricing quote from an insurance company because the remaining participant liabilities are more complex and riskier to handle.

Another item to consider is whether an organization would be better off in the long run maintaining a fully funded pension plan that is generating income and showing a surplus on their balance sheet instead of going through the expense of a voluntary plan termination. Moreover, changes in plan design can impact an organization’s ability to attract and retain the quality employees it needs to remain competitive.

For those plan sponsors who are considering paring down their DB plans and intend to offer replacement benefits through a DC plan, it is important to give thought to the kinds of replacement plans that are available in addition to risk-sharing levels between employer and employee. Moving to a DC plan that offers the same benefit replacement level as a DB plan will generally increase costs for a plan sponsor. Conversely, moving to a DB plan that offers a lower benefit replacement level may result in employee dissatisfaction and defection.

Risks also exist with respect to plans that already have pension surpluses. The following comments are also relevant in the event of an interest rate spike for a plan that is near fully funded status. A corporate plan’s overfunding does not get returned to the plan sponsor, unless the plan is terminated, and even then, there is the cost of risk transfer in the form of plan termination and in most situations, a hefty 50 per cent excise tax on remaining surplus assets. Thus, while it is prudent to fully fund a plan, the risk of overfunding does exist and plan sponsors must carefully plan out dynamic LDI strategies when their ultimate funded status goals are reached.

In summary, while plan sponsors have dealt with more than their fair share of pension volatility over the past two decades, there have certainly been many options available to help smooth the journey. While it is prudent for plan sponsors to monitor pension risk, it is important to exercise care in the strategy that is chosen and in the timing of implementation. Every pension de-risking strategy has its own pluses and minuses and most have associated embedded costs, whether implicit or explicit. Risk management strategies must be customised for organisations depending on risk tolerance and risk budget requirements. It’s not a one-size-fits-all approach and that’s what makes it both challenging and rewarding for pension actuaries as they work together with plan sponsors to help them achieve their plan objectives through design and prudent management.

Zorast Wadia is a principal and consulting actuary with the New York office of Milliman.