In the Chinese language, the word “crisis” is composed of two characters — 危机 (weiji): where危 (wei) means crisis or danger, 机(ji) means opportunity.

Crisis to be sure, China is in a deep one. As of early February 2020, there were approximately 60,000 known and confirmed Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (NCP) cases and over 1,300 deaths worldwide. At least 28 countries and territories have been affected with no sure sign of peaking. The virus rampaging across China is already more damaging than SARS which killed 349 people in the country.

Can this crisis be turned into opportunity?

Today, much of mainland China remains shut down as authorities try to limit the spread of the virus that started to emerge in early December. The outbreak started in Hubei Province’s Wuhan, a city of 11 million people and a major transportation hub. What made things worse is that it happened just when the country’s most important holiday — the Lunar New Year — was about to start with hundreds millions of people travelling across the country, forming part of the world’s largest annual migration projected to represent 2.5 billion people migrating across many regions from January 10 through February 9.

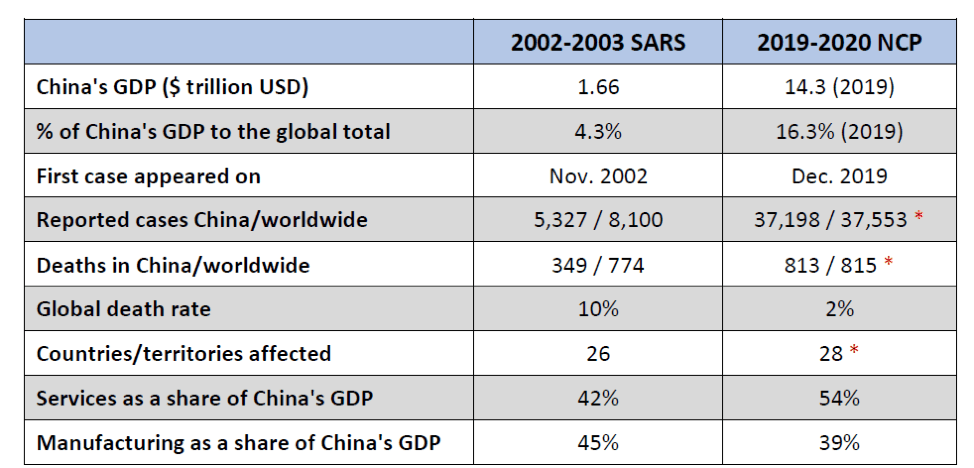

China is also more integrated into the global economy than in 2003 when SARS broke out. Back then, China’s GDP was only 4.3 per cent of the global economy, while by 2019 that number had increased to 16.3 per cent. During the SARS period, lockdown measures were not taken by any city in China (including the epicenter in Beijing). This time, well over half of the country is locked down for weeks. Businesses started to slowly reopen on February 10, but the government is advising further postponement for a week or more and most schools will not open before March.

The services sector saw its biggest impact in over a decade. While the Lunar New Year is traditionally peak season for restaurants, retailers, online e-commerce, entertainment and tour agencies, lockdowns have abruptly brought these businesses to a standstill ever since leading Chinese CDC expert Zhong Nanshan announced the contagious nature of the virus on January 21.

By then the virus had been spreading throughout the country with roughly 5 million people leaving Wuhan for the holiday season.

Oxford Economics forecasts that the US alone will experience a loss of 1.6 million visitors from mainland China this year, translating into 4 million hotel room nights.

* Data as of Feb. 11, 2020. Source: WHO, Chinese CDC, IMF, National Bureau of Statistics, Huang Zhong.

When SARS broke out in 2003, China had entered the WTO just a year prior and the economy was able to recover back to double-digit growth. When the coronavirus broke out, China had just signed the Phase One Trade Deal with the US and the economy had already experienced its slowest pace of growth in three decades to 6.1 per cent in 2019.

The Shanghai Stock Exchange was finally able to resume trading on February 3 after the Lunar New Year and the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index lost 7.72 per cent, the biggest drop since 2015. Some economists have predicted a full half percentage drop of GDP growth from 2019. A few even project a 1.5 per cent drop to 4.6 per cent for all of 2020. Some have accepted the proposition that a 0 per cent growth rate might be the reality for the first quarter of this year.

Because of China’s increased integration with the global economy, the ripple effects from China are much wider than during the SARS outbreak, particularly to Asian countries that benefit from China’s insatiable demand for materials largely coming from the upgraded lifestyles of the growing Chinese middle-class population, the largest in the world.

The crisis is far from over. In fact, the peak of this crisis has yet to show itself.

But it’s never too early to start reckoning as to what went wrong.

For its part, China needs to seriously look at its governance practices, and issues repeatedly criticised by the West.

When ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, 34, passed away in the midnight of February 6 after “futile efforts at resuscitation,” it sparked an outcry on Chinese social media about the Communist Party’s attempt to censor information on the epidemic.

He was one of the eight whistleblowers “reprimanded” by police for “spreading false rumors and misinformation” — information that turned out to be largely true — a month before Zhong Nanshan officially recognised the novel coronavirus’ vicious nature of person-to-person transmission.

Li was hailed as a hero on Chinese social media for his bravery in speaking up. But internet censors wasted little time trying to tamp down the buzz. The deletion of commemorative and criticising posts has further fueled anger over censorship behind the Great Firewall which most “netizens” have already gotten used to. But now such censorship attracts enormous pushback across the country. “What else can you do other than delete our posts?” one post asked.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria are a set of standards used by responsible investors to screen a company’s operations, but most people don’t realise that a sophisticated ESG model can also be applied to evaluate the sustainability of governments.

Responding to environmental and social demands from the public is any government’s intrinsic responsibility.

China has made a lot of great, ongoing efforts to tackle its environmental issues such as smog, polluted water and the carbon-intensive energy sector. It’s becoming the largest green bond market and the world’s leader in new energy vehicles and related technologies. It is also determined to eliminate absolute poverty by the end of 2020, effectively having lifted over 800 million people from humanitarian crises within 40 years. [See the forthcoming book on Modern China available April 2020.]

Governance has been used by investors to understand that a company uses transparent methods and that stockholders are given an opportunity to vote on important issues. They may also want assurances that corporate strategies in management structure, employee relations, consumer protection, board diversity and human rights are sustainable even under extreme external and internal crises.

Should the Chinese government and its ruling party have applied some basic sustainable investment principles, it would have taken a very different approach towards critical stakeholders such as Dr. Li and potentially avoided some of the negative consequences.

After all, sustainability is “development that satisfies the needs of the present without compromising the capacity of future generations, guaranteeing the balance between economic growth, care for the environment and social well-being.” (From the seminal Brundtland Report)

Time and again, China has proven itself capable of pulling off large scale initiatives for the betterment of the country’s economic, social and environmental conditions.

By learning ESG strategies from successful investors, the country can truly become a world model for achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs).

Learnings from this crisis are also bi-directional: China should learn to be more transparent and give its current governance strategies a deep and honest review, while the rest of the world should learn from China and its ability and speed to mobilise, learn, adapt, innovate and build.

The Chinese government, an authoritarian regime, was able to build the 1,000-bed Huoshenshan Hospital within seven days, and the 1,500-bed Leishenshan Hospital within 10 days, something that the West arguably never imagined could happen. Once the government decided to act, its response and response capabilities have shown what China can do.

The central government quickly mobilised the entire country to host patients from Hubei province whose healthcare system was already overburdened and is on the brink of total collapse. Using a strategy called “one province — one city”, the country is quickly sending thousands of confirmed patients from 16 cities other than Wuhan to their “helping provinces”. For example, Jiangsu is taking in patients from Huangshi City; Guangdong and Zhejiang province taking patients from Jingmen City.

This large scale, cross-territory mobilisation and cooperation is exactly what the world needs to solve large, complex, imminent and consequential threats such as climate change.

While the crisis is still ongoing, entrepreneurs in China have already been thinking about how to integrate IoT, automation, and AI into traditional “low-tech” manufacturing processes.

For example, a mask manufacture in Suzhou has already started experimenting full-automation for its N95 mask product line to replace labor intensive processes such as manually gluing mask straps. The product line only needs one worker instead of five. This conversion only took five days to happen, instead of five months.

The Huoshenshan Hospital is another example of how China is pioneering advanced AI and robotic technologies to try to be “contactless” between infected patients and health caretakers to reduce the risk of exposures to the deadly virus.

In between, you have innovations such as Kentucky Fried Chicken and Alibaba’s Hema food delivery service trying to add App features for contactless delivery, allowing couriers to leave orders in convenient places for customers to pick them up, without requiring interaction.

Businesses across the country are also learning to “home office” or “cloud work”, which few have tried before even though internet connections are almost ubiquitous. Government offices are also quickly moving many of their bureaucratic, mundane and often unnecessary face-to-face procedures online, which also improves efficiency and transparency.

Masks are a relatively low-tech product, but these new production techniques already demonstrate further possibilities for applying more advanced automation and IoT technologies to be “smart,” flexible and economically useful. While other countries are still monitoring the situation, practical innovations are already happening and scaling up at “China Speed” to become real opportunities that the rest of the world can benefit from.

Climate change, poverty alleviation, zero hunger, air and water pollution, biodiversity, sustainable cities and communities are all environmental and social sustainability imperatives which require massive global coordination and grassroots innovation. Transparency and better governance are prerequisites not just for individual corporations, but also to every responsible country and their governments and ruling parties.

China must learn from its past and current epidemic crises and other social crises such as SARS and the Hong Kong protests.

Transparency, sharing and cooperation are the only ways to solve pressing global crises that may very well threaten every country and person on this planet.

China and the rest of the world are much more integrated than they were 17 years ago, and they will only bind more tightly going forward. In a decade, China will be the world’s largest economy. It will inevitably assume more leadership roles on global affairs.

Will China seize the opportunity it has in hand to become the country most able to solve global sustainability challenges?

Cary Krosinsky and Huang Zhong are from the Sustainable Finance Institute.

Krosinsky was also on the New York State Common Decarbonization Advisory Panel