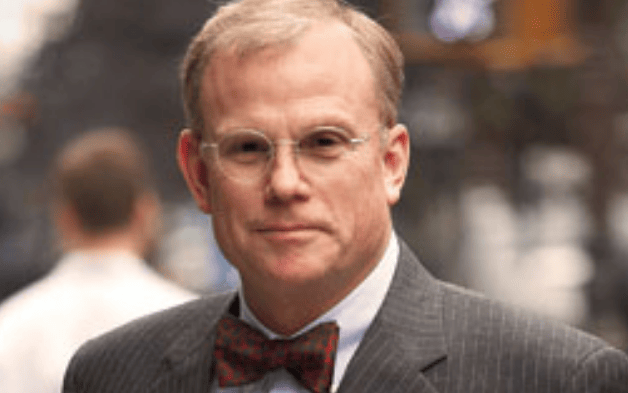

Professor Stephen Kotkin stops to consider the rollercoaster ride in politics, leadership and policy making that we have seen globally over the past few months. Who will win? What does the future look like? And how will the global economy restructure for survival?

China is winning, American leadership is a deadly shambles. Then, China’s early failures, lies, and finger pointing have provoked a fierce global backlash, while America’s governors and laboratories inspire hope. Autocracies are the winners, democracies the losers. However, democracies are using their advantages, and autocracies have flopped. Singapore showcased its superior governance model; Singapore inflicted upon itself a second wave outbreak (by ignoring its essential migrant labor force). Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders flamed out at the ballot box; but the programs Corbyn and Sanders ran on are now being enacted, including modern monetary theory. Markets are crashing. Markets are sound and recovering. Russia won the oil tussle with Saudi Arabia; actually, Riyadh administered a hiding on Moscow; no, everyone lost the oil pique. The global lockdown shows we can and we must fight climate change. The global lockdown shows the impossible costs of fighting climate change. “There can be no return to normal because normal was the problem in the first place,” the graffiti in Hong Kong says. Worldwide people pine for a return to normalcy. Globalisation is over. Globalisation is anything but over.

Whiplash anyone?

Early on in a potentially epoch-defining crisis is not the time to render definitive judgments.

Most experts agree that the coronavirus will precipitate sweeping changes. They just disagree irreconcilably on what those changes will be. Sages mostly seem convinced that the world following the pandemic will accelerate in the very direction they have been warning about or advocating for since before the pandemic.

One matter on which there is a deceptive consensus: this is a war. We will know if our coronavirus responses are an actual war – as opposed to the politicians’ and pundits’ go-to metaphor – if income is decisively redistributed, but in the opposite direction of the past four decades. Of course, the more consequential issue will be whether we see dramatic moves to address inequality of opportunity.

Historically, we have inflated our way out of these situations. But business forecasters cannot confidently predict whether the economic consequences are going to be high interest rates and inflation, from a lack of savings and lingering supply chain disruptions against a need to reinvest massively; or low interest rates and deflation, from a glut of savings and cautious consumers amid a quickly reopened economy. Both are plausible – as is an unforeseen new abnormal.

Back in 1921, the American Frank Knight (1885-1972), a founder of the celebrated Chicago School of Economics and a teacher of multiple Nobel Laureates (Milton Freidman, George Stigler, James Buchanan), published his PhD dissertation on the entrepreneur, Risk, Uncertainty, Profit. He argued that risk entailed unknown outcomes, but that intelligent bets could be placed based upon probability distributions derived from similar situations in the past. All investing was a form of applied history. Uncertainty, however, was different. It involved not just an unknown but also an unmeasurable possible future. Knight’s distinction between risk and uncertainty opened up divergent paths to profit. Uncertainty enabled profits that even perfect competition could not eliminate. To put the matter another way: risk can be priced well or badly, but there is a form of risk that cannot be priced.

The game of seeing around the blind corner has always been a seductive one. Otherwise smart people will even pay the players of it. What is coming? Food insecurity. More failed states. An authoritarian wave. Socialism. Commodity price shocks. China’s takeover of the world. The Asian Century. The unravelling of the EU. Few players see positive developments around the corner. Who is going to pay money for good news?

Well, there is good news aplenty. Trust is now and forever will be the most valuable attribute in business, society, and politics. Trust takes some time to build, and only moments to squander. But even when lost it can be recaptured. And when we can draw upon it, trust delivers.

Democracy is feckless and frustrating, to be sure, and yet dispersed power and authority make possible exceptional initiative and entrepreneurship: the leadership of local officials, the diligence of sceptical journalists, the nimbleness of the private sector, the sense of vocation among professional and service personnel. Yes, coherence and central coordination are desperately wanting, even in better times, let alone in a catastrophe. Still, not needing policemen on every corner or censorship of the public sphere is genuine strength.

Finally, what can seem like folly is often the ancient dilemma of the tradeoff. Just in time efficiency is the greatest cost saving measure of all time, until it becomes crushingly expensive. Resilience is prohibitively expensive, until it delivers priceless salvation.

Remembering lessons is somehow always harder than forgetting them. And yet, learning is possible, as we see all around us. You just have to look.

Professor Stephen Kotkin will speak at the Fiduciary Investors Digital Symposium to be held online June 23-24. The event is only open to asset owners.