The geopolitical stresses already present in the global economy have been further fractured by the current crisis, especially the relationship between the US and China. What can we learn from history and what it all means for institutional investors?

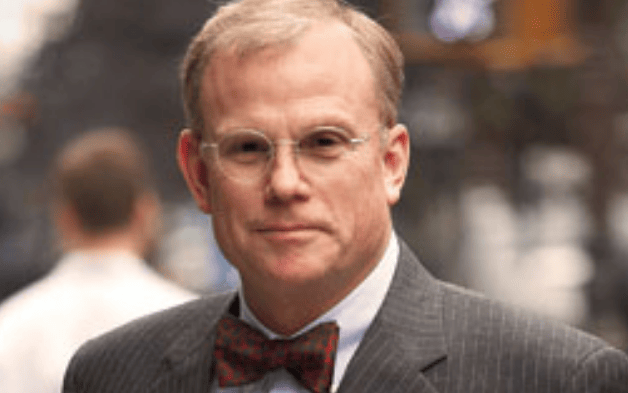

Stephen Kotkin

Professor in History and International Affairs, Princeton University (United States)

Professor Kotkin received his PhD from the University of California, Berkeley in 1988, and has been a professor at Princeton since 1989. He is also a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

At Princeton Professor Kotkin teaches courses in geopolitics, modern authoritarianism, global history, and Soviet Eurasia, and has won all of the university’s teaching awards. He has served as the vice dean of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, and chaired the editorial committee of Princeton University Press. Outside Princeton, he writes essays and reviews for Foreign Affairs, the Wall Street Journal, and the Times Literary Supplement, among other publications, and was the regular book reviewer for the New York Times Sunday Business section for many years. He serves as an invited consultant to defence ministries and intelligence agencies in multiple countries. His latest book is Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941 (Penguin, 2017). His previous book was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Colin Tate has been an investment industry media publisher and conference producer since 1996. In his media career, Tate has launched and overseen dozens of print and electronic publications. He is the chief executive and major shareholder of Conexus Financial, which was formed in 2005, and is headquartered in Sydney, Australia. The company stages more than 20 conferences and events each year – in London, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Amsterdam, Beijing, Sydney and Melbourne – and publishes five media brands, including the global website and strategy newsletter for global institutional investors conexust1f.flywheelstaging.com. One of the company’s signature events is the bi-annual Fiduciary Investors Symposium. Conexus Financial’s events aim to place the responsibilities of investors in wider societal, and political contexts, as well as promote the long-term stability of markets and sustainable retirement incomes. Tate served for seven years on the board of Australia’s most high profile homeless charity, The Wayside Chapel; and he has underwritten the welfare of 60,000 people in 28 villages throughout Uganda via The Hunger Project.

Key takeaways

- The pandemic has not changed geopolitical risk in any significant fashion because five megatrends that pre-date the virus have stalled and there remains no resolution in sight:

- Islamism in power has hit a brick wall

- Communist China is unable to move forward with political liberalisation

- The Reagan-Thatcher synthesis has run out of steam

- The EU is stuck

- Globalisation is still undermined by a lack of global governance

- The stagnation of these megatrends is worrying but the US-China relationship is the one item that could blow up the world.

- The US-China geopolitical risk is enormous and unpriceable and could impact all other trends.

- The US-China clash is not a misunderstanding, it is a fundamental clash of values. The clash is real and the clash is permanent. Assuming we cannot eliminate these differences, can we at least manage them? Deterrents need to be deployed to dissuade bad behaviour, but so does diplomacy and incentives for positive collaboration.

- It is wrong to question whether we will enter into a new Cold War – we entered one a long time ago. Although a Cold War is better than a hot war.

- China fears Hong Kong as an alternative model of freedom, politics and law. Asia will not work economically if it doesn’t work politically and geopolitically.

- The US has corrective mechanisms – such as elections – however any election correction will not be as extreme as some expect. Don’t just watch Trump vs Biden, watch the Senate. For many people Biden is the political vaccine that the US needs, but he is disorganised and has lost the election more times than anyone.

- The Putin regime has also hit a brick wall. His menace is eroding in terms of his capabilities, not necessarily in terms of his behaviour.

- Chinese society is breathtaking in its dynamism and entrepreneurialism. All credit to their rise. Let us find a way to manage that. The challenge in not the Chinese regime, the challenge is China itself.

- Global progress can and must be founded on domestic solidarity.

Unanswered questions and answers

Q: How do you foresee the crisis in Hong Kong playing out? How will the western countries respond? Do you expect significant financial market turbulence driven by the politics at this financial hub?

A: Stephen Kotkin: Hong Kong’s unique role as a financial center was already feeling strong competition from newer financial centers on the mainland, such as Shanghai. So the relative decline of Hong Kong’s supreme importance was happening independent of politics. But Hong Kong still has advantages and is still very valuable to any regime in Beijing, even if the latter dismisses Hong Kong’s value.

More broadly, Hong Kong is a remarkable achievement and needs to be preserved for the benefit of China as well as the world. Hong Kong deserves far more credit than it usually gets for the mainland miracle. People often say to me Russia should have gone down the Deng Xiaoping path instead of the Gorbachev path; I say, well, Russia had no Hong Kong. Other countries should pressure Beijing to lighten or repeal its security law, not pressure Hong Kong by repealing the special status it has been granted by foreigners. Beijing signed a treaty on Hong Kong and is violating that treaty. Punish the violator.

Q: Arrogance and insecurity is how you describe China. Is the US really any different? Asked by Stewart Brentnall, TCorp (Australia)

A: Stephen Kotkin: Yes, the same fatal combination of supreme arrogance and profound insecurity has been evident sometimes in US behavior internationally. It is a characteristic of superpowers that have any domestic legitimacy weaknesses or whose elites are worried about relative decline abroad. A key difference is that the U.S. has greater legitimacy for its system as well as crucial corrective mechanisms at home. Abroad, US alliances are voluntary and allies can influence US behavior in significant ways. Citizens and partners can temper US behavior. So despite some similarities, it is different in significant ways.

Q: What is the realistic path for Europe? What about the US / European relationship? Asked by Joel Whidden, Bridgewater Associates (United States)

A: Stephen Kotkin: One possible realistic path for Europe is to introduce a Northern Euro. This would be a voluntary currency that some countries could join if they wanted to and if they met certain criteria. Everyone else would be left inside the existing euro. The latter countries could choose to remain or exit. Exits in those circumstances would not be fatal to the larger idea of a Union. It would instead be a way for countries to reintroduce their national currencies, for greater flexibility and legitimacy, without undermining their ability to participate in other institutions of Europe. The current euro has to go, but in a way that does not throw the baby out with the bathwater for those countries’ publics that want to remain in a Union of some sort.

Another pathway would be greater humility on European powers versus national powers. The European leaders who want to create a political federation have no chance to achieve their aims. This is not a realistic path forward. But even now, without a federation, the European court powers override nearly everything domestically. This is not the case with most federal systems by the way, let alone for systems that are not federations and have no chance of becoming one. A rebalancing of prerogatives is not a way to undermine the Union but to strengthen it. This is a controversial point for those who consider themselves “pro-Euroepan”.

The Transatlantic alliance of shared values and institutions – what we call the West – should be sustained. The “China threat”, however real it is in terms of threats to freedom and rule of law, is not sufficient to hold the Western community together. There must be a positive vision, too. The shared values and institutions need articulate and resolute defenders. It is tragic how in the U.S. conservatives insist Western Civilization should be taught at universities but they detest the European Union, while liberals in the U.S. oppose Western Civilization courses yet celebrate the EU.

The security relationship remains out of balance by fault of both sides: the US for inhibiting for a long time a European desire to become more self-reliant in defense, and the Europeans for not maintaining the necessary level of capabilities or finances for collective defense with the US. This can be fixed but has not been because of the seeming binary quality of the choice: either invest everything in NATO, or invest everything in a common European security instead. And we get neither.

Where things get much harder is translating the Transatlantic partnership to a greater global partnership of ‘Western’ countries that share institutional and value commitments to democracy and the rule of law. Here, Japan fit into the West (institutionally). Australia fit. But much of Asia will be uncomfortable with that category. South Korea, Taiwan, India, and others are all crucial partners, but not Transatlantic, obviously. Even if the ‘West’ stretches beyond the West geographically now, we need to invent a new basis of solidarity of shared values and institutions without the original geographic term. Here, our marketers could help out!

Q: You are an expert on Russia, Stalin and Stalinism. In your discussion of megatrends, you don’t mention Putin, Stalin’s successor. Can you comment on Putin’s effect on the world, particularly his continuing intervention in western elections, military interventions in Syria, Ukraine and others?

A: Stephen Kotkin: If I am correct that the main megatrends in the world are mostly culs-de-sac, stagnant without obvious paths forward, Russia, too, falls into that category. The Putin trajectory, which did so much to rescue the Russian state from the 1990s ongoing collapse, performed that rescue with the kind of methods that undermined that rescue over the long term. As a result, Russia’s state is again eroding, and the Putin regime is a prime culprit. The primary victims of the Russian regime are Russians, though. They lack sufficient diversification in the economy, investment in human capital (on the contrary they are hemorrhaging human capital), investment in infrastructure, or good governance (governance is deteriorating). The regime is muddling through, but without a way to move the country forward.

As for Russia’s behaviour abroad, it can indeed be nasty. But we exaggerate their influence. Syria is a civil war and a ruined country. Russia has little to no strategic gain from Syria. Russia’s interference in US elections backfired horribly on their reputation, and achieved little to nothing of practical value (and did not affect the election outcome). We need to differentiate between tactical gain – which is what happens on cable television – and strategic gain, which is what happens when your country gets stronger: more investment in human capital, infrastructure, good governance. Russia’s adventurism abroad has delivered next to no strategic gains. This is important to keep in mind as we assess how to counteract such behaviour.

Poll results

Who do you think will (not who do you want to) win the election in the United States this November?