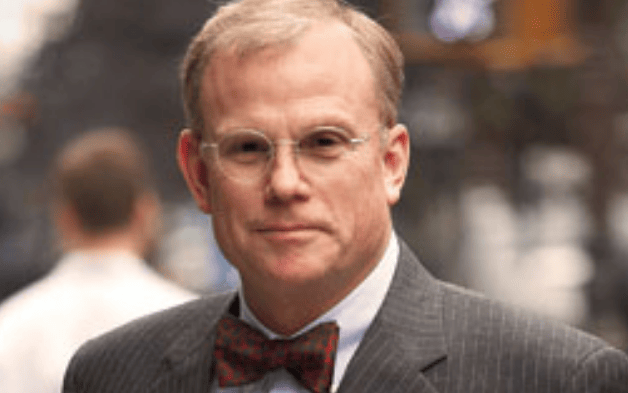

Unemployment is a policy choice, according to Professor Bill Mitchell, the father of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). He says there is no reason that unemployment should be at the current levels.

This is after the jobless rate in the US spiked to 14.7 per cent in April, after hovering around 3.5 per cent for much of the previous year. For context, the highest unemployment rate during the global financial crisis was 10 per cent in October, 2009. In Australia, the Reserve Bank said it expects unemployment to be at 10 per cent until next year.

“That’s a policy failure,” says Mitchell in an interview, who is Australian. “There are plenty of things that can be done.”

Mitchell, who is Chair in Economics and director of the centre of full employment and equity at the University of Newcastle and a visiting professor at Maastricht University, says government stimulus packages around the world are about half as much as what is currently required. He says that the fear of debt should not drive policy.

One of the core beliefs of MMT economists is that the fiscal position should be a floating position, and not the ongoing focus of attention.

“We need to ask what the purpose of fiscal policy is,” he says. “It’s not ever to achieve a particular number, that type of statement is meaningless because its context free. Fiscal policy is to make sure that total spending is sufficient to provide enough demand for the productive resources to be employed and we can enjoy material prosperity in a sustainable way.”

He adds that if non-government spending falls or collapses, like what is happening now, then the government deficit needs to float upwards. “There’s nothing to it,” he says. “The fiscal deficit shouldn’t be the focus of our attention, it should just float.”

Mitchell does, however, acknowledge that this crisis sparked by the pandemic is different to the past because of the supply shock.

“Typically a recession needs demand stimulus to support growth, but in this crisis there is a peculiarity because the lockdown is causing the unemployment and output contraction,” he said. “Generalised fiscal stimulus could be dangerous because it will hit a supply chain bottleneck quite quickly. Governments have to be cautious about how to stimulate the jobs and output recovery. We need the productive system to respond so we don’t get inflation.”

The bottom line, according to Mitchell, is that governments need to be smart and creative about the solutions, and that there are many ways to put the unemployed back to work, and also avoid supply chain issues.

“They need to think through the problem and not create secondary problems as a consequence of not dealing with the initial problem properly,” he says.

Instead of a wage subsidy, and keeping people idle in unemployment, he says the government could cover employee wages and put them to work in other areas such as infrastructure rebuilding.

“I would have preferred the government to cover wages fully, which is fair wage distribution and everyone gets protected for the time being,” he says. “In this country we have had bushfire devastation that means we need infrastructure rebuilt.”

Mitchell says the government could then tell people who can’t work in hospitality, for example, that they will pay them to do that work.

“Most workers would agree as part of a national emergency,” he says. “Similarly most of our food harvest is done by backpackers, which is low skilled work. We’ve closed our borders so that is causing a supply chain problem. Already we are starting to see food prices rise, and farmers digging food into the ground because they can’t harvest or sell it.”

Importantly, history has proven that if people are unemployed for more than a year it is very difficult to get back into work.

“This is one of the reasons governments should do everything they can do to stop the recession,” Mitchell says. “The longer a recession goes on, those workers become very distant to the labour force, their skills start to atrophy including their social skills and their networks shrink. And as the economy starts to grow again the pool of unemployed is so large that the economy has to grow really fast to absorb the short term unemployed, the long term unemployed and new workforce entrants.”

Avoid mainstream economists

When it comes to fiscal deficits, Mitchell advocates that investors should avoid listening to mainstream economists who believe that we will see a massive spike in bond yields and an acceleration of inflation, which would “predicate moves away from long positions in government bonds”.

“During the GFC, traditional economists got investment banks to move to real assets because of predicted inflation, and they lost investment opportunities in government debt,” he says. “None of that happened. They tried to get people to short government bonds thinking they’ll be a price collapse. None of that will happen. There won’t be a massive spike in bond yields in sovereign debt anywhere except in some of the most disadvantaged countries.”

“We need to get away from that narrative that this debt will be a future burden and will require taxes, and bond prices will fall,” he adds.

Instead, Mitchell says the fiscal stimulus should be thought of in the context of rebuilding the economy and creating real opportunities in the future. He points to investment in virtual communication and technology infrastructure, environmental solutions and personal care services.

“This will be the worst economic downturn that we can ever imagine, worse than the Great Depression,” he warns. “The difference is we won’t have a massive financial collapse because central banks are bailing everything out.”

“Central banks are buying all the government debt,” he says,. “Japan paved the way to show the monetary and treasury components of the government sector should operate that way. You don’t have a collapse if you do that, and keep interest rates low and maintain low unemployment. Ultimately at the end of this current stimulus period, the Reserve Bank will hold all the state and federal debt. The right pocket of the government is paying the left pocket. It’s a non-issue.”

MMT, which Mitchell has been advocating for more than 25 years, is new ideology about what governments can do with economic policy.

“MMT is about lifting the veil, it’s a discussion about what it is that governments can do. That is what democracy is about,” he says, arguing that it has been in the best interests of the top end of town to keep the average person in the dark about economics.

“One of the contributions of our work is that once you understand the capacities of the currency issuer are real not financial then the policy space opens up considerably,” he says. “We are not saying that deficits don’t matter, but that the policy space is much wider and there is more flexibility in what governments can do than what we think they can do. There is no reason for unemployment to rise right now, it’s a policy choice. We could redirect all that labour to do functional things.”