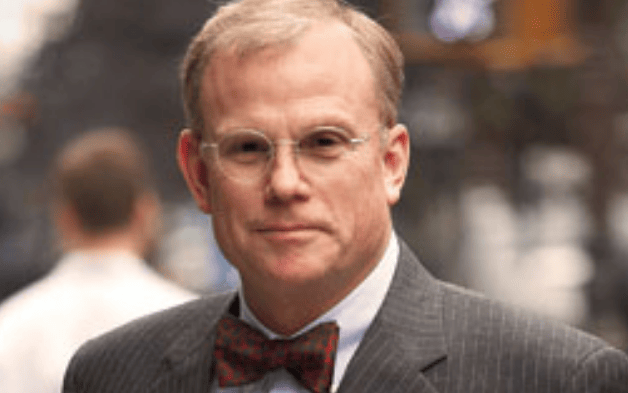

The COVID-19 pandemic is the second global economic crisis that Ash Williams has endured as the executive director and chief investment officer of the $200 billion Florida State Board of Administration. Williams re-joined SBA in his current role in October 2008, in what might be called challenging timing. But there is something unique about this crisis that is keeping Williams up at night and which hovers over his view of the portfolio’s direction.

“There is a disconnect between financial markets and the real economy which beggars the question: Is there embedded misery in the economy that has not yet played out in financial markets?” he asks.

Williams says that the GFC was a completely different experience from the pandemic because it was an economic crisis that evolved from excesses in certain sectors and systematic misalignment between buyers and sellers. In this current crisis the financial markets bounced back, but in the underlying real economy the “recovery is not there”.

In terms of managing the SBA portfolio through the pandemic, Williams says the most important step was to make sure at the onset of the pandemic the fund had ample liquidity.

“Our fundamental obligation is to meet benefits in a timely way,” he says.

The amount of capital required to meet those obligations was calculated and set aside, as well as the money needed for any potential capital calls, and rebalancing. Only then was liquidity considered for opportunistic investments.

“The first thing we did was to position ourselves for liquidity. The difference between being a predator and prey is liquidity,” he says in a Fiduciary Investors Series podcast interview.

In terms of making the most of the opportunities, Williams saw the disruption in markets as an opportunity to invest more in active management.

“When you look at the way we deployed the rebalanced assets and bought back into equities markets one of the judgements we took was to put a higher exposure into active management,” he said. “There were whole sectors like hospitality and transportation which have been depressed and devastated and there’s no way to know when that would end. So why have a routine exposure to those sectors, why not have an active manager make some judgments on that?”

SBA also made some allocations to distressed credit opportunities and some private equity speciality funds.

“In real estate we did a kind of joint venture between real estate and strategic investments. Early on in the pandemic we saw isolated seizures in security markets, and one of the first things that came under stress was publicly traded REITs, they had a lot of leverage and had problems meeting their obligations. This was an early source of stress and created a period of disconnect between prices of trading REITs and what the underlying assets were worth. With an existing REIT partner we helped form a new vehicle to take advantage of the short term dislocations in the REIT space,” Williams says.

Since then he is keeping a close eye on the significant real estate portfolio and sold a few assets.

“Retail and office have question marks over them and we’ll see how that plays out,” he says. “One of the biggest unknowables is what happens to office real estate. Look at NYC as an example there’s been closure of office buildings and an exodus of people. If you’re in a city it’s usually for the vibrant culturally elements, but when everything is closed all you’re left with is living in a small space at a high price and it’s not as fulfilling. It’s also led to hot markets in second home and resort areas in the US. How many people come back to a conventional daily presence in an office, it’s too early to say. We do believe the creative processes of humankind are stimulated by people being together, more than a video conference can support. Probably offices will come back but it remains to be seen as to how and what that looks like.”

Elsewhere some parts of the portfolio that are actively managed have benefited, such as the overweight to tech and venture in private equity, and certain parts of the RE book have benefited from healthcare exposures.

For the most part the portfolio hasn’t changed a great deal on the liquid market side. In fixed income there has been a slight move towards enhanced core or core plus.

“We are trying to gain a bit more return by way of credit. Extending duration doesn’t seem terribly appealing in this environment,” he says.

Enterprise risk management

SBA has around 200 people in the team and they started operating remotely in early March. The fund has a head start on testing systems endurance and every year gets to test remote working due to hurricane season. It has good business continuity plans in place and this played out in a seamless move to working from home.

In terms of risk management Williams says the most important development in recent years has been a move from a focus on portfolio risk to an enterprise risk basis.

Williams says risk tolerance, the quantitative measure of investment risks, budgeting for them and having an understanding of aggregate risk is of vital importance. But what that doesn’t reflect is risks that have nothing to do with the portfolio but everything to do with the enterprise, and they are equally important in protecting outcomes and achieving objectives.

“A cyber breach could cause reputational damage well beyond the investment loss,” he says by way of example. “The biggest risk that we face and all public pension funds face, is not portfolio risk; it’s political risk. If you look at the history of pension fund failures around the world more often than not the cause is not a shortfall in investment return, it has been a failure of funding.”

SBA has a nine member investment advisory council where members are required to have institutional fiduciary experience. This complements the board of three trustees which are all state-wide elected officials and who don’t necessarily have institutional investment experience.

SBA already manages a significant amount of assets inhouse, which has been a big contributor to its low costs, and Williams says there will be more assets managed in house.

“We have superior results and very low costs and a big part of that is the ability to manage money inhouse. We have an understanding what is realistic for us to do inhouse, we would never compete with Canadian funds who are equipped to do direct private equity by example. But we can do passive, factor investing and maybe a bit of co-investment,” he says. “A penny saved is just as good as a penny earned. You need human capital and talent to do it prudently, we have that.”

About the Fiduciary Investors Series

Through conversations with investors and academics, the Fiduciary Investors Podcast Series, is a forward-looking examination of the changing dynamics in the global economy, what a sustainable recovery looks like and how investors are positioning their portfolios.

The much loved events, the Fiduciary Investors Symposiums, act as an advocate for fiduciary capitalism and the power of asset owners to change the nature of the investment industry including addressing principal/agent and fee problems, stabilising financial markets, and directing capital for the betterment of society and the environment. Like the event series, the podcast series, tackles the challenged long-term investors face in an environment of disruption, and asks investors to think differently about how they make decisions and allocate capital.