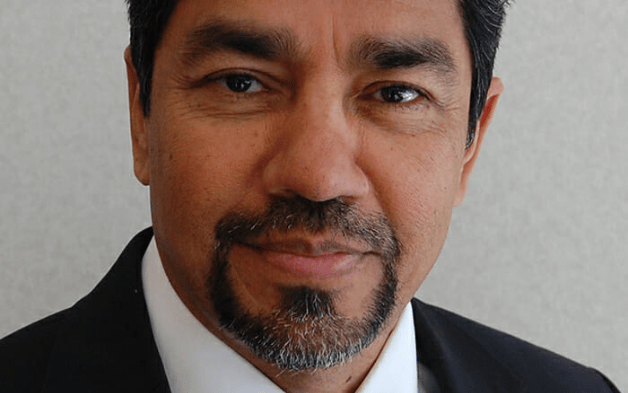

Farouki Majeed is worried about the future. His concerns are centred around the implications of the enormous federal debt in the US and borrowing from the future; the global competitiveness of the US economy in particular when it comes to its competitiveness with China; inflation; and the potential erosion of the value of the US dollar. He talks to Amanda White about what it means for his portfolio allocations.

“The economy is picking up,” says Farouki Majeed, chief investment officer of the Ohio School Employees Retirement System, citing travellers passing through the domestic US Transportation Security Administration returning to pre-pandemic numbers as an indicator.

“I expect the economy and markets to continue to head upwards for a while – even though they are at lofty levels – because they are supported by all this stimulus,” he says. “It’s a strange world.”

But like many CIOs around the world Majeed thinks the near-term outlook is pretty good, but he has many concerns about the medium to long term outlook for markets and the economy.

“The near term looks good. A year ago, I was looking at charts like the 1930s and looking at how long it takes to get back to normal, which historically has been a long time,” he explains. “We were worrying ourselves to death about how it might pan out. Who would have thought a year would change so much? We have had 21 per cent return so far this fiscal year. There is one more quarter to go and we are hoping to hold on to that.”

Majeed’s concerns in the medium to long term are centred around the growing debt burden and the implications of that on markets and on returns.

“There is huge stimulus in the US and it is all being borrowed from the future. The latest round of stimulus probably went a little too far. The new administration is trying to incorporate some of their other agendas into the COVID relief which is fine in the short term, but it’s a lot of money.”

Majeed points out the $27 trillion debt bill in the US has pushed the debt-to-GDP ratio to 130 per cent, up from 91 per cent a decade ago and 55 per cent 20 years ago. At the time of the market crash in 1929 the debt to GDP ratio was 16 per cent.

“We have that federal debt to GDP and have never seen such erratic prices at that level. That will be a drag on future economic growth,” he says.

Beyond the debt situation his lists of concerns go on, including the global competitiveness of the US economy in particular when it comes to its competitiveness with China, inflation, and the potential erosion of the value of the US dollar.

As an investor, Majeed’s job is to figure out how these concerns and opportunities can be reflected in the asset allocation, and he has taken an approach that is not rigid in the allocations by trying to fill asset class pots but looking at the overall portfolio and what is missing.

“We have not made any strategic decisions to say X per cent in inflation hedges or other hedges for these scenarios. But what we are trying to do is incorporate aspects in the portfolio we are not currently doing. Some funds have put allocations to [for example] gold in their strategic asset allocation in the last year. We have not done that, but we are reflecting that in our portfolio in small ways via strategies. It’s putting our toes in the water so we can ramp up those allocations as we need.”

Commodities and gold are two examples of this, where investments are not part of the SAA but they are in the portfolio and allocations can be increased as appropriate.

“Commodities will have a fairly big demand and leg up in the coming quarter. We don’t have a strategic allocation to commodities but I want to have a way to ramp it up.”

Defensive allocations

The other big question for the portfolio is the bond allocation.

“Owning US government bonds is a dead-end kind of game at this point,” Majeed says. “That is a concern so we are looking for alternative ways of hedging equities in the portfolio while trying to generate more income return.”

The fund now has up to 5 per cent in a private credit allocation that it didn’t have a few years ago. It followed the same path by dipping its toes and investing in private credit strategies and then graduating that into a new asset class.

“I haven’t quite figured out is what is a good substitute for a fixed income allocation. If we underweight fixed income I want to make sure we are doing it judiciously and incorporating other assets to fill that role such as TIPS, gold, ILBs,” he says. “For so long bonds have filled that defensive role and had decent returns. We have had a period of 30 plus years with a secular decline in interest rates and the 10-year treasury has gone from 15 per cent to 1.5 per cent. There are some that are saying the 10-year could be at 2 per cent by the end of the year. How rapidly it goes up depends on how inflation pans out. If the US Fed is forced to begin some kind of tightening regime, that would be a consternation in the markets.”

Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell has said tightening will not begin until 2024 but Majeed is pondering whether he will be forced to act given all the stimulus and global growth picking up.

“If the economy is at 6 per cent over the next quarters the Fed might be forced to act” he says. “If that happens then it’s a potential risk to the market. The bond markets are already indicating they really don’t believe the Fed and it might happen sooner. We have to wait and see.”

At the end of 2019, Ohio SERS had been reducing its equities allocation with a view that markets were quite high, so it had some cash going into the crisis. This enabled it to deploy assets into some opportunistic investments including “a lot in credit”.

“Many companies were being squeezed and needed credit to get by. We invested quite a bit in credit strategies and high yield and this helped our return in this period.”

But while many investors would be pleased with the 21 per cent return so far this year, this adds to Majeed’s concerns.

“It means that forward returns will be quite dismal I think because we are borrowing from the future. Valuations are high. Equities and credit valuations, high yield, all are pretty high. Even real assets in certain areas are high.

“Valuations are very rich and likely to stay like that in the near term, because [of] all the liquidity and stimulus pumped into the economy. That is going to go somewhere, and I think it is going to elevate commodities and bring in some inflation.”

Majeed does concede there are opportunities in some real assets that have been quite badly impacted by COVID and could be some opportunities in the re-alignment in real estate for example.

He is looking to increase the fund’s infrastructure allocation which is currently around 3 per cent of the total fund from a standing start five years ago.

Hedge funds have been reduced to a zero-target allocation drawn down from 15 per cent when Majeed joined the organisation eight years ago. He does use hedge funds where there is confidence in the strategy, but they sit within other asset class allocations.

“I really think having a target allocation to hedge funds is ill-advised, we use hedge funds as an active management strategy within other asset classes depending on the underlying investments,” he says.

Some of that hedge fund allocation has gone into private credit and real assets.

“One of the goals was to improve income return. That is going to be crucial in coming years. If we have stable income return that will be a protection in this kind of market,” he says.

The fund is not looking to deploy any explicit hedges, but instead trying to incorporate implicit hedges within asset allocation and portfolio construction.

“We are exploring and thinking about it.”

Forward looking returns and the next crisis

With returns for the next 10 years destined to be well below those of the past 10 years, pension funds in the US may be forced to focus on matching liabilities rather than return targets.

“I think with the the 10-year yield is at 1 or 1.5 per cent what will happen is that matching liabilities as a conversation will feature more with boards, versus that of the return target of 7.5 per cent, ,” he says. “5 per cent above is a tough target. Our board has been trying to grapple with this issue and we have a conversation on pension fund sustainability on a pretty regular basis. Our hands are tied in the sense there is very little you can do. The solution is on the benefit side but cutting benefits is not a popular thing. Risk is also increasing. And we could potentially have people drawing benefits for longer periods. I wouldn’t want to be a CIO five or 10 years from now. It’s a tough equation.”

Majeed says while equities have returned excess of 10 per cent over 10 years for the fund, over the next 10 years he is expecting more like 5 to 6 per cent, with bonds likely to be 1 to 2 per cent.

“I have been in this business for 30 plus years. In the last 10 to 12 years we have had two major crises, who would have thought? In a way we are setting ourselves up for another – because of the debt and the stimulus. I don’t know what form it takes but you can see a lot of speculation. Look at Bitcoin, people are reaching out for these types of things. It will correct itself via some sort of crisis.”

As people around the world emerge from lockdown and communities get vaccinated there is talk of some return to normalcy. But Majeed’s view is that normal will be different to the past.

Some of the areas where change might be pervasive and impact the state of normal is how consumer behaviour might have been impacted and will play out in certain types of asset classes. Or the housing boom, or the impact of the COVID crisis on the young population and their sentiments and behaviours going forward.

“There is quite a bit of uncertainty I think. There will be some realignment and readjustment. Smart investors will have to catch on to them and hopefully we can do some of that.”