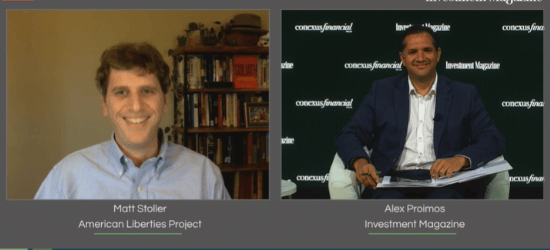

Concentrated power by monopolistic companies is a systemic problem in the US economy, according to Matt Stoller, director of research at the American Liberties Project, but investors have little power to change it.

Speaking at the Investment Magazine, Fiduciary Investors Symposium, he said these companies – such as Google, Facebook and Amazon – are producing stellar returns for investors, but they are not being matched with actual wealth creation.

“When financial returns are not being matched with wealth creation you have a serious accounting problem in society writ large,” he said. “What these firms are doing to get a 20 to 30 per cent annual return is just capturing market power, they are not creating wealth.”

This mismatch between what the financial systems indicate is happening in society and what is actually happening is dangerous, he said.

“We have a low interest rate environment and a lack of places to invest. It is really hard to start new firms which has implications for investments. If there is not new stuff, factories, innovative content and products then ultimately there won’t be places to invest money.”

Stoller believes that social corporate responsibility is a distraction in general. And while some corporate leaders were responding to employee demands, all the corporates really care about is regulation, tax, trade and anti-trust.

“I don’t think pension funds have that much power,” he told the audience.

Concentration is a systemic feature of the US economy, he says, and can be seen in various sectors from technology to peanut butter and portable toilets.

Historically Americans were very suspicious about monopolies and concentration of power, but a movement in the 1970s led by Milton Friedman and the Chicago University School of Business intellectualised concentration as a positive structure and good for efficiency.

“They argued that concentration of big business wasn’t a political problem, it wasn’t about anti competitiveness, but existed because they were efficient and good at things,” Stoller said. “They argued to policymakers they needed to unleash the concentrated capital to make the world more efficient and handle the inflationary environment of the 1970s.”

As a consequence there was consolidation in many sectors including retail, defence, energy and banking, all in the name of efficiency which was measured by low prices.

With that backdrop and the digital revolution in the 1990s and 2000s companies such as Amazon and Facebook were born native to monopolies, Stoller said.

“These firms are enormously powerful and consequential, and a result of the political economic revolution and tech revolution,” he said. “That has created this political crisis where a small group of people are setting terms over our markets and societies.”

Stoller says tech firms are the pace setters of the economy and are deeply embedded in the infrastructure of the economy.

“The power of these firms goes beyond the traditional, these firms are replacing government and public infrastructure with their own infrastructure and becoming somewhat sovereign in themselves.”

Stoller advocates for breaking up these monopolies, in part because he acknowledges how difficult they are to regulate due to their complexity.

“These firms are so complicated. They have soft influence which creates problems with democracy but they are impossible to regulate as is, because they are so complex and embedded,” he said.

At the American Liberties Project Stoller and the team are focused on the problem of private power including how to simplify these companies.

“We need to engage in structural separation, break them up. That conversation is starting to accelerate, to simplify these business models so we can regulate them.”

Stoller said the large tech firms such as Google and Facebook are not innovating and are holding back innovative.

“At first you could argue they were innovative and doing things people found useful. Now they are more a function of a series of mergers and probably they are holding back innovation all over the world,” he said.

The most obvious sign post for this he said is in media.

“Local news gathering and local newspapers are dying. We all have these super computers that are our phones that are vehicles for story telling but we don’t have financing models to build news in an innovative way that you would normally see. This is because of the ad models and these companies holding that back.”

Stoller said over history there have been many times that concentrated power has been reigned back in, and the post-1970s era of big is good is very uncommon in the US.

“There has been a fear and suspicion of monopolies back to the Civil War. What changes things in democracies is the public making different decisions about what they want,” he said. “How we structure markets is political, it doesn’t come out of nature. Out of the GFC we saw a tremendous dissatisfaction from the public in how we organise our markets. Now we are in the throes of the debate once again.”

He also warned that concentrated power is not just big tech firms, but pointed to China as an example of market power.

Stoller outlines in his book Goliath: The hundred year war between monopoly power and democracy, that what is being discussed now around these companies is a resurrection of these much older debates.

“There were a number of different ways the Chicago school instrumentalised their vision on to our economic order. One was relaxing how we approached anti-competitive behaviour, another way was restrictions on capital and who can borrow.”

Predatory pricing was illegal in the US before 1975 but is now commonplace. He said it empowers companies to borrow from Wall Street and price below cost, driving out people who can’t access the financial markets.

“The Chicago people would say that’s good for consumers. But what that ends up doing is privileging firms with closer access to capital, and int today’s environment of financialisation, the closer you are to central banks gives you enormous competitive advantages to wield power and influence how we interact with each other.”

Stoller said that the Ivy league universities in the US were a big part of the problem.

“This is fundamentally a battle of ideas. Economists have a mathematised language which makes them an agent of monopolies,” he said.

For more reading on monopolistic power see: Finance mirrors tech monopoly behaviour