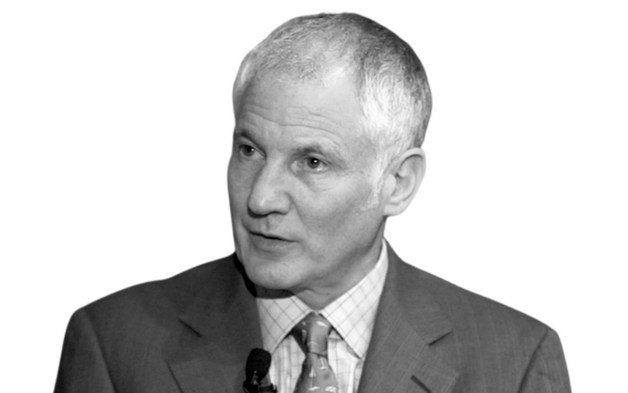

ESG-focussed investors are having a hard time justifying their China exposures to their boards, and will need to develop new narratives if they want to stay in the China game, argues historian Stephen Kotkin.

Two decades ago it was only perceived naysayers who were warning that China was unlikely to become the largest economy in the world or posed a threat to world order over its stance on Taiwan, says historian Stephen Kotkin, noting he himself was one of those naysayers.

Speaking at Conexus Financial’s Sustainability in Practice forum at Harvard University, Kotkin said that in the face of slowing economic growth making it harder to make money in China, and China’s rhetorical support of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ESG-focussed investors are having a tougher time justifying their China investments.

At the start of the millennium, in the face of China’s remarkable accomplishment in lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty, alongside the United States’ culpability in the Global Financial Crisis and the Iraq War, those talking about Western resilience and the problems inherent in the Chinese model were seen as being on the wrong side of history.

“Those of us talking about that had a difficult time connecting with the investment community because there was so much opportunity that seemed available and there was, as I said, a lot to answer for on the US side,” Kotkin said.

But it turns out this side may have been correct–at least on China’s long-term trajectory if not on the timing–argued Kotkin, senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Freeman Spogli Institute at Stanford University, and Birkelund Professor Emeritus at Princeton University.

Despite China’s stunning achievements, there are three fundamental problems in the Chinese development model “that have now come home to roost,” Kotkin said.

The first is the middle income trap, and the historical fact that it is much easier for a country to leap from low-income to middle-income than it is to go from middle-income to high-income. Looking at China’s education levels in particular, it would be “a miracle and against the run of history” if China were able to break through the middle-income trap.

Despite high absolute numbers of highly-educated people, China has 700 to 800 million people “who are outside the world economy,” with less than a high school education and almost no healthcare. China’s high-school-or-above graduation rates are the lowest for any middle-income country, he said.

“Many of them can’t even get prescription glasses,” Kotkin said. “There’s this giant population that the country didn’t invest in.”

The second problem is the demographic issue as China gets old before it gets rich. Lacking a social safety net for the vast majority of the population, getting old is a significant problem because there is no way to care for these people, he said.

“If you’re watching the pandemic and you’re puzzling over why the regime is locking everything down when they get one case, or three cases, or five cases, it looks ridiculous except if you know the size of the old age population; the lack of medical care, especially intensive care beds,” Kotkin said.

The third problem is investment-driven growth and the difficulties of transitioning to consumer-led growth. This has yet to happen despite officials talking about it for a long time, Kotkin said.

“No economy has ever had this much investment-driven growth this deep into its growth story,” Kotkin said. “It’s over 40 per cent and of course, a lot of that is waste; it’s misallocation of capital because they’re just pumping the GDP numbers and now we know that from the housing debacle.”

But the deepest problem is the Communist Party monopoly which “cannot reform itself successfully.” Liberalising the economy could only go so far before it threatened the party’s monopoly, leading to a crackdown on the private sector and increasing investment in state-owned enterprises, he said.

It is common knowledge inside Chinese government circles that the party cannot open up without committing suicide, Kotkin said.

Now with ESG high on the business agenda, Kotkin said he sometimes jokes that “the CIA invented ESG as a way, finally, to get the business community to stop being a cheerleader for China, because everything else the CIA tried failed.” When the Communist Party is put through ESG metrics, investing in China loses some appeal, he said.

China’s treatment of Tibet, Xinjiang and even Hong Kong share similarities with Russia’s treatment of Ukraine, he said, just as China’s rhetorical support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is also problematic.

With the above-mentioned structural problems reducing the ability of investors to make money in China, compounded with ESG concerns, there are a range of arguments investors will use to stay in the game, Kotkin said.

Engagement

Some investors may decide to engage with the hope of effecting change from the inside. China’s important role in the energy transition may also boost these views.

“It’s important because, as you know, China accounts for 50 per cent of global use of coal and that number is skyrocketing because China’s building 258 brand new coal-fired power plants as we sit here,” Kotkin said.

But the engagement argument is a difficult argument to make, because “the Chinese don’t care what you think,” Kotkin said.

However the Chinese government’s push for self-sufficiency may lead to greater use of renewables to reduce its reliance on oil and gas which are imported, he said.

Other investors may stay exposed to China arguing that Chinese society is extremely dynamic, and that they are betting on China’s “people and its human capital, in its talent, in its future, and its dynamism,” which unfortunately means being “in bed with the regime to a certain extent.”

Other investors may seek to capture some of the growth in China without being China-centric, seeking plays on the growth and dynamism of developing societies around the world that will leave them less dependent solely on the China story, he concluded.