The impact of climate change on investing presents a big challenge. Learn how investors are tackling the risk.

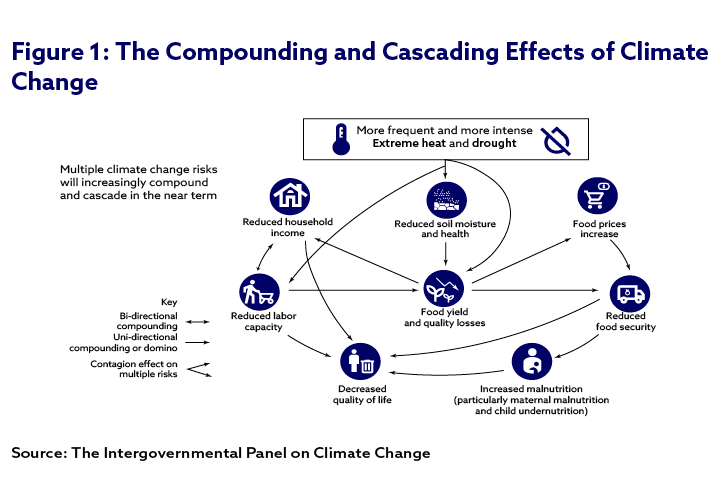

When people envisage the impacts of climate change risk, they tend to picture the physical risks: soaring temperatures, rising seas, failing crops, species loss, hunger and strife.

Overview

Images of island nations disappearing under the waves might come to mind, while worsening heatwaves, droughts, wildfires and floods are already evident. These will collectively take a considerable toll on household income, food security and quality of life around the world. Across a diversified portfolio, the transition risk could be thousands of times greater than the physical risk, according to Michael Lebbon, Founder & CEO at Emmi, a firm which helps financial institutions understand and analyze the climate risks of their assets and portfolios.

“Transition risk moves very quickly,” said Lebbon, speaking on CFA Institute’s recent Climate is Collective Webinar about Understanding Climate Scenarios. “If we actually had policies that are aligned to a 1.5°C world today, by some estimates, over half the global value of stock markets could be lost overnight.”

Physical risk, on the other hand, takes hold over a much longer timeframe, giving firms more opportunity to adapt. The worst physical impacts are also likely to be felt in less-developed countries, where there are fewer material financial assets.

The Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommends organizations use scenario analysis to develop strategic plans to prepare for transition and physical risk. They can draw on one of more than 100 publicly available climate scenarios or construct their own to anticipate a range of plausible future outcomes based on varying assumptions about policy and technology developments, macroeconomic factors, population growth, greenhouse gas emissions trajectories, and behavioral and societal changes.

Investors use scenarios to assess potential implications of climate-related risks and opportunities, and to inform stakeholders about how the organization is positioning itself in light of these risk and opportunities.

Widely used scenarios within the financial industry are developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and International Energy Agency (IEA).

“There’s really no one-size-fits-all. You have to see which scenario best meets your requirements,” said Sonia Gandhi, Senior Director, Education at CFA Institute.

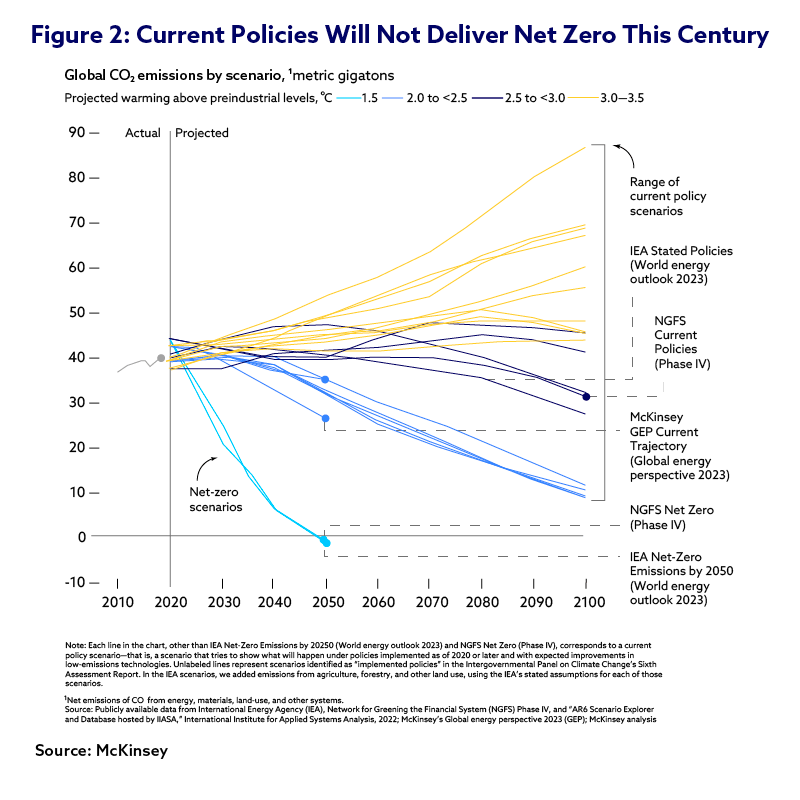

One thing that all the main scenarios make clear is that policy, as it stands, falls short of limiting warming to 1.5°C, which is considered vital to achieving net zero by 2050 (see Figure 2).

Although 145 countries covering close to 90% of global emissions have announced or are considering net zero targets, the Climate Action Tracker assesses the majority of these as insufficient. It states: “We are a long way from converting net zero targets into policies and actions that will result in real-world emissions reductions.”

As the physical effects of climate change risk become increasingly visible, however, many, including the Principles for Responsible Investment – a United Nations-supported network of investors working to promote sustainable investment – believe it is inevitable that governments “will be forced to act more decisively than they have so far”.

Carbon Pricing

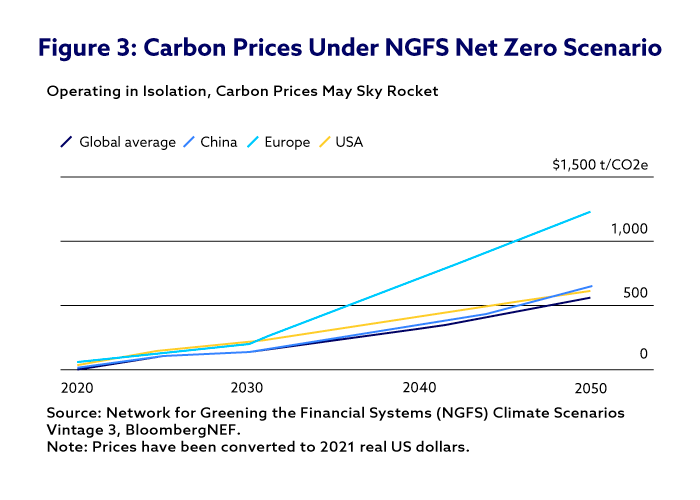

As policy ratchets up, so will transition risk for organizations and investors. Among the expected measures are higher carbon prices, as regulators seek to hold carbon-intensive businesses accountable for their impact on the environment. Gandhi describes carbon pricing as “one of the most potent tools in combating climate change”.

Carbon pricing can take the form of either a direct tax on emissions or a cap-and-trade scheme, where an overall limit is placed on emissions and businesses buy and sell credits on a mandatory carbon market. Examples of cap-and-trade schemes include the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), California Cap-and-Trade Program and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative covering 11 Eastern US states.

“With cap-and-trade schemes, the market determines the price of carbon,” said Gandhi. “The limit on emissions is usually gradually lowered over time to incentivize a lower use of carbon intensive processes.”

As that happens, the price of carbon credits would increase. And as pressure to address climate change risk mounts, governments will likely implement and ramp up direct emissions taxes.

For investors, carbon prices provide a valuable reference. “It basically tells you how much people think reducing carbon is worth. And then from there, you can make more informed investment decisions around that price,” said David von Eiff, Director, Global Industry Standards at CFA Institute.

Both the NGFS and IEA net-zero scenarios foresee steep increases in carbon prices up to 2050 (see Figure 3).

This is necessary because the closer the world gets to net zero, the more expensive it will become to remove each incremental unit of emissions. Technologies such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and sustainable fuels are currently too expensive to be commercially viable. That could change rapidly, however, as higher carbon prices and other policy measures draw investment to climate technologies, enabling them to scale.

In all, nearly USD1.8 trillion was invested in clean energy and other climate mitigation measures globally in 2023. But low-carbon transition research provider BloombergNEF calculates that investment would need to average USD4.8 trillion per year from 2024 to 2030 to achieve net zero by 2050. Higher carbon prices could help bridge the gap.

While high carbon prices could also fuel inflation and cause socioeconomic disruptions, there could be significant social benefits from decarbonizing too: according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, a 1.5°C pathway would lead to a 1.7% increase in average annual employment in the 2023 to 2050 period.

Moreover, shifting to lower-carbon alternatives can lead to cost savings, with clean energy technologies often cheaper over their lifespans than those that rely on fossil fuels. Since clean energy projects often have a high initial cost, access to finance is seen as crucial to achieving those savings.

Preparing for a Low-Carbon Future

In June 2024, UN Secretary-General António Guterres sounded a warning: “We are playing Russian roulette with our planet. We need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell. And the good news is that we have control of the wheel. The battle to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C will be won or lost in the 2020s – under the watch of leaders today.”

As leaders eventually take action, transition risks will come to the fore. Companies and investment portfolios that seek to measure and manage those risks ahead of time stand a much better chance of weathering the storm than their less-prepared peers.