“A forecast is a prediction; we’re saying what we think will happen. A scenario is different . . . it generally looks much further out and is trying to build a picture of the future in extreme uncertainty.” — Seb Henbest

By Florian Forster, CFA

It is impossible to predict the future without some level of uncertainty. When we make investment decisions about assets with multi-decade horizons, our forecasts will ultimately break down. But while we do not know what the 2050s will bring, we can envision pathways that provide reasonable variations of what that future may look like. For investment managers, prioritizing one scenario over all others can have far-reaching consequences.

This is especially true when it comes to the net-zero energy transition.

There are multiple, equally valid pathways through the transition, all with different technology mixes and varied time horizons. Hence, a simple discounting of cash flows in a somewhat predictable “economic” scenario — with rational actors reacting to techno-economic considerations and the policies that are likely to be enacted — is not necessarily viable. Energy investors must consider various outcomes since the outcomes are, well, so various.

Research providers, think tanks, sell-side analysts, and industry groups all compete for investors’ attention. Their goal is to either win our business or influence our decision making. Their base case often depends on their background.

Those with histories in oil price assessment or renewable energy modeling could be prone to availability or anchoring bias. Many big energy players with high exposure to an abrupt net-zero transition construct their own scenarios, often guided by their own agendas. Gas transmission system operators (TSOs) and their industry groups envision a bright future for their stakeholders, whether through extended use of natural gas or rapid shifts to hydrogen. For example, Shell’s “Energy Transformation Scenarios” — Sky 1.5, Waves and Islands — attracted a lot of attention: Its Sky 1.5 pathway assumes a larger role for oil and gas than forecasts issued by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other such bodies. How hydrogen will fit into the energy mix of a climate-neutral Germany is also much discussed, but there is no consensus on how large a role it will play or from where it will be sourced.

Given the abundance of organizations promoting their own scenarios, investors need to approach them cautiously. We recommend a three-step assessment process:

- Apply some filters and screen out obviously conflicted forecasters.

- Review the target forecasters’ scenarios and decide which are most applicable to your investment philosophies.

- Consider the investment target’s performance and how plausible pathways could diverge from their presumed base case, which is often the “economic” scenario. This is where careful evaluation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors and the resulting risks can help assess how the future may stray from the anticipated path.

There are other things to keep in mind. Social factors may drive higher emissions scenarios. Rising energy costs could impact spending on heating, transport, and food. By increasing the cost burden on the low- to middle-income population, such “greenflation” could lead to widespread political and social unrest. Policymakers might be pressured to subsidize fossil fuel consumption. This has already occurred in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia and constitutes a potential headwind that could delay our eventual exit from fossil fuels.

Of course, the tailwinds driving us away from traditional fuel sources may be even more powerful. Shock events have strained supply chains, and volatile fuel prices encourage calls for a renewable path to energy independence. Climate change–related risks are top of mind for much of the population, and as climate-related crises grow ever more severe, popular support for sustainability should translate into public policies that help propel the world towards a 2050 net-zero scenario.

In addition to policy developments, transformative technological innovations are also possible. Indeed, small modular nuclear reactors may deploy faster than expected or the costs of hydrogen from electrolysis could fall below $2 per kilogram earlier than anticipated.

Choosing Our Path

Some investors might be tempted to allocate based on their economic case and assume no significant technological or policy shifts. But they have to consider the possibility that these investments could become stranded and prepare accordingly — to either take the hit or extract sufficient value beforehand.

Alternatively, some investments may transition themselves. Carbon assets have transition potential, provided they have a future in a hydrogen-based fuel scenario or can be retrofitted for carbon capture and storage (CCS). Both paths could contribute to achieving net-zero by 2050. But will they? We don’t know. There is too much uncertainty around the ultimate cost and effectiveness of transitioning such assets, especially when they could be displaced by lower-cost technology.

The most prudent approach, then, may be to focus on no-regret assets. These will likely perform across all the most viable pathways of the energy transition: More renewables, more short-term and long-term storage, a stronger grid, heat pumps, and district heating should all be central to a carbon-free future.

When faced with such critical decisions, we need to explore scenarios beyond our economic base case. We cannot assume rationality among all actors: The transition to net-zero won’t be smooth. There will be periods of slow progress, potentially followed by abrupt changes in the face of extreme weather events, technological advancements, political upheaval, pandemics, or other developments.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.

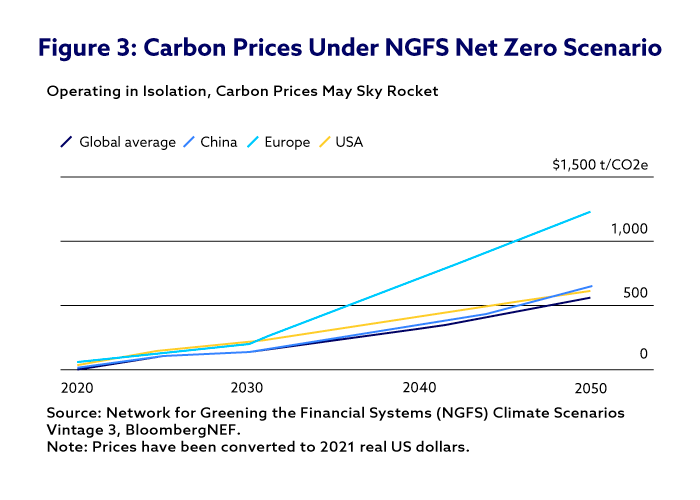

This is necessary because the closer the world gets to net zero, the more expensive it will become to remove each incremental unit of emissions. Technologies such as carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and sustainable fuels are currently too expensive to be commercially viable. That could change rapidly, however, as higher carbon prices and other policy measures draw investment to climate technologies, enabling them to scale.

In all, nearly USD1.8 trillion was invested in clean energy and other climate mitigation measures globally in 2023. But low-carbon transition research provider BloombergNEF calculates that investment would need to average USD4.8 trillion per year from 2024 to 2030 to achieve net zero by 2050. Higher carbon prices could help bridge the gap.

While high carbon prices could also fuel inflation and cause socioeconomic disruptions, there could be significant social benefits from decarbonizing too: according to the International Renewable Energy Agency, a 1.5°C pathway would lead to a 1.7% increase in average annual employment in the 2023 to 2050 period.

Moreover, shifting to lower-carbon alternatives can lead to cost savings, with clean energy technologies often cheaper over their lifespans than those that rely on fossil fuels. Since clean energy projects often have a high initial cost, access to finance is seen as crucial to achieving those savings.

Preparing for a Low-Carbon Future

“When you start exercising regularly, you also get more conscious about your diet. There’s a similar dynamic when you put a price on carbon. You become more conscious about everything else that you’re doing around it and start taking other actions to reduce emissions,” said Gandhi.

Still, internal carbon prices generally have a long way to go to meet the Paris Agreement’s target of keeping global warming to less 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, noted Gandhi.

With the global average temperature reaching 1.45°C above pre-industrial levels in 2023, the hottest year in recorded history, that limit is close to being breached.

In June 2024, UN Secretary-General António Guterres sounded a warning: “We are playing Russian roulette with our planet. We need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell. And the good news is that we have control of the wheel. The battle to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C will be won or lost in the 2020s – under the watch of leaders today.”

As leaders eventually take action, transition risks will come to the fore. Companies and investment portfolios that seek to measure and manage those risks ahead of time stand a much better chance of weathering the storm than their less-prepared peers.