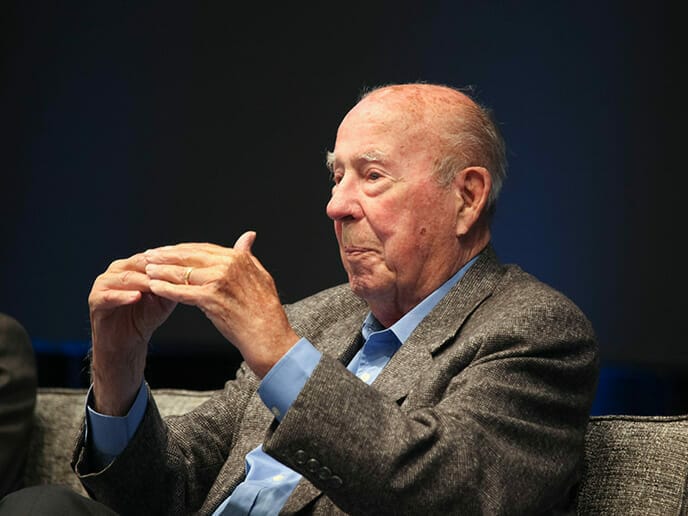

It is possible to meet the challenge of climate change successfully by introducing a carbon tax, celebrated veteran politician and academic George Shultz said.

Shultz spoke at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Stanford, where he is Jack Steele Parker Professor of International Economics, and told delegates that research and development were keys to managing climate change.

Rather than regulation, which holds back economies, he said, a gradually rising, revenue-neutral carbon tax would use “the marketplace” to cap carbon production.

“It works, and it will work in this case,” he said. Shultz noted broad support for the tax and referenced his work with the corporate sector, including major oil companies.

“Companies whose names you would recognise have signed up for a revenue-neutral carbon tax,” he told delegates. “More companies see it as better than the regulatory hand.” His next step is to garner political support amongst Republicans in the US Congress.

Shultz also noted the crucial role research and development play in meeting the challenges of climate change. The amount of federal support for energy research and development in the US is small, but he said federally funded programs had proved they nurtured ideas that drew the private sector. “Private people come on board, and private money is 3 to 1 [over] public money,” he said. He noted that adding business expertise to research programs brought scale and important collaborative relationships.

He cited the innovation climate research and development has already produced.

“It is a fact – the energy research and development people are getting somewhere.” Solar is competitive in price, car batteries are smaller, lighter, less expensive and more powerful, he said.

“The electric car is here,” he proclaimed. He also said scientists were “on the cusp” of solving challenges around storing large amounts of renewable electrical power that would take the intermittency problem out of solar and wind power.

Shultz argued that innovation on climate change required thinking about solutions that wouldn’t hold back economies, and that research and development held a global buy-in, since they create products and services people use.

“I’ve had solar panels on my house for 10 years and have long-since paid for them from money saved,” he said. “And they produce more electricity than my electric car uses, so the cost of my fuel is zero. What’s not to like?”

In a wide-ranging discussion that referenced Shultz’s own extensive career and close personal relationships with US presidents, he told delegates that governments act only when there is a “major event”; however, he explained it was possible to include disparate groups that jostle and disagree, via broad action plans.

Shultz cited how former US president Ronald Reagan, for whom Shultz was secretary of state, committed to the Montreal Protocol in 1987 without “demolishing” those who disagreed that the ozone layer was in danger.

“Reagan put his arm around the disbelievers,” he said. At a time when politics is fractured, Shultz talked about the importance of a two-party system, rather than a multi- party system, which he said would lead to poor decision-making and leadership.

President Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement would not stop America’s states and cities from developing their own climate solutions, Shultz said, something he said reflects a new federalism taking shape across America, in which state governments are effecting change, rather than Washington.

“Washington is broke,” he said. The political system is unable to handle difficult problems and people want more control over important aspects of their lives nearer to where they live. Challenges such as rising interest rates, high debt and the healthcare crisis won’t be resolved by Washington politicians, he said.

“The chances of Washington facing up to this and doing something are zero, but in California we can do something.”

Shultz did note, however, the importance of global co-operation in tackling climate issues. It led him to reflect on the need for leadership to stop nuclear proliferation, a global struggle he called a “crime” and likened to climate change. He said deploying nuclear weapons had become “loose talk” and that people had forgotten the destruction they wreaked.

“We have got to get to grips with them,” he said.