In this year’s International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) annual review we highlighted four trends in sovereign wealth fund direct investments in 2018: private markets bouncing back, the acceleration of early-stage investments, the age of new urban mobility, novel partnerships and co-investment structures.

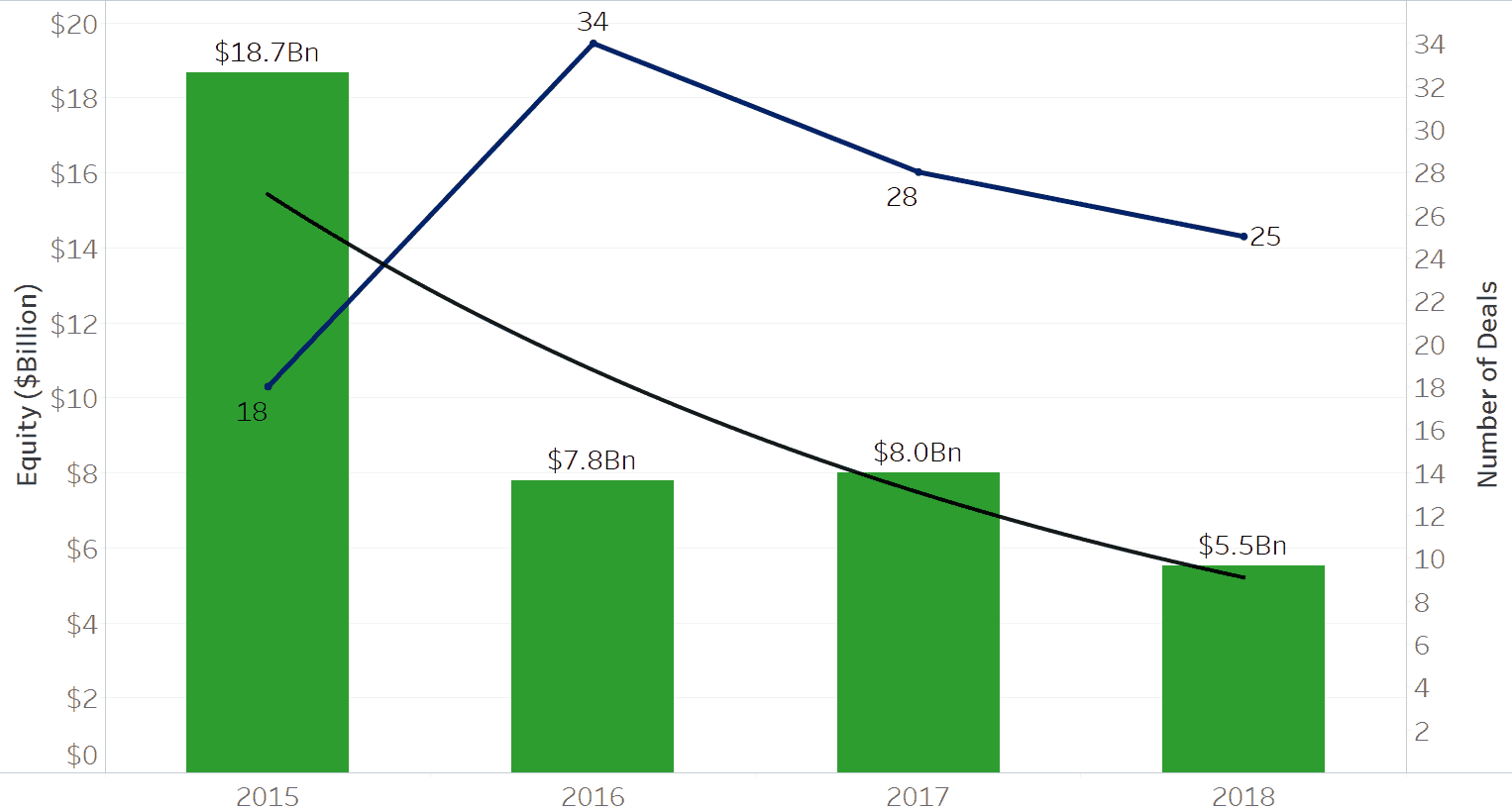

Some of these trends apply to infrastructure, with SWFs sourcing fewer transactions in hard assets. In 2018, SWFs invested 30 per cent less in infrastructure than they did the previous year, $5.5 billion in 2018 down from a total of $8 billion in 2017. The number of investments also dropped by 10 per cent from 28 to 25. This is not a one-year aberration, but a downward trend from the peak of $18.7 billion committed in 2015.

Chart 1.1 SWF Direct Investments in infrastructure

Source: IFSWF Database

Renewables: a gateway to climate change opportunities.

Global investment in renewable energy hit $288.9 billion in 2018, with the amount spent on new capacity almost triple the amount invested in new fossil fuel power, according to a report published this month by BloombergNEF, as a part of UN environment thinktank REN21’s Renewables 2019 Global Status Report.

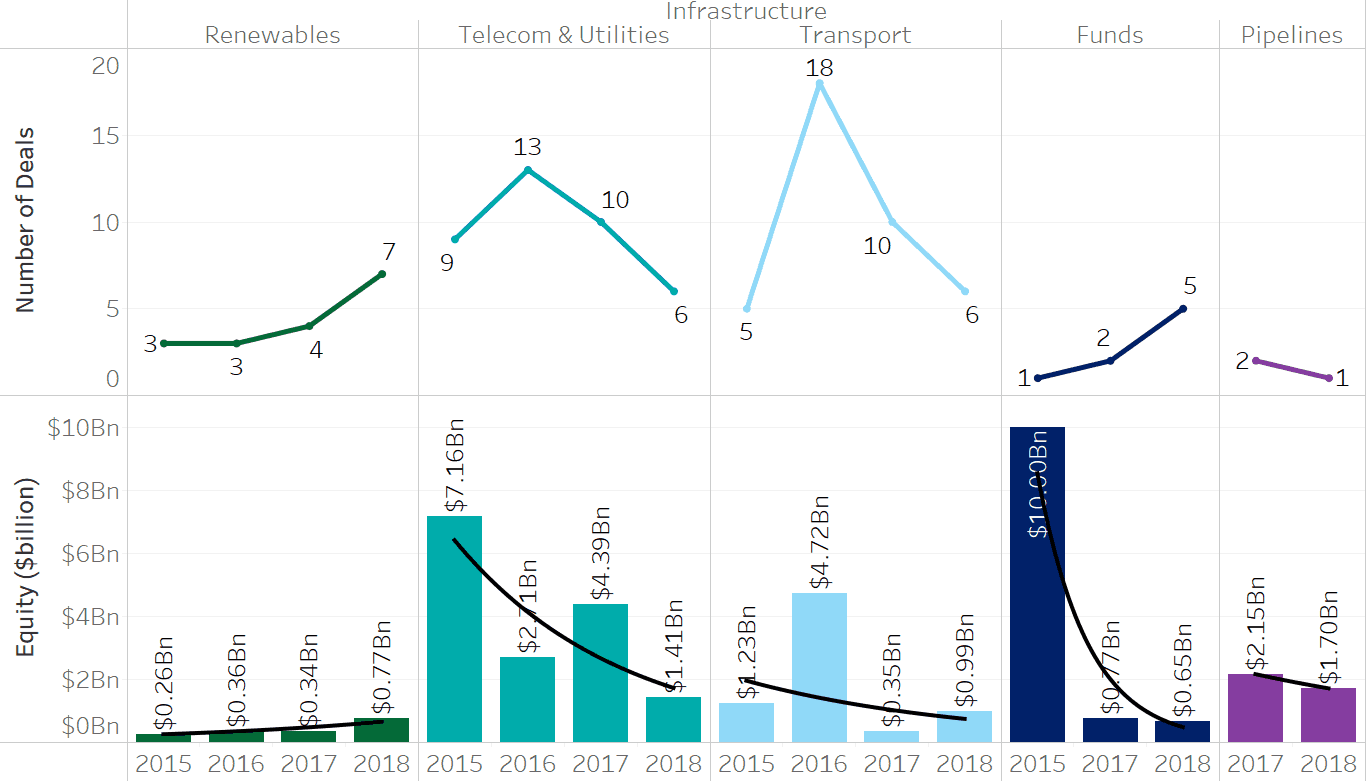

SWFs took advantage of the growing number of opportunities to finance renewable-energy projects in 2018, primarily co-investing with both asset owners and asset managers. According to IFSWF data, SWFs provided the most equity financing for renewable energy companies since 2015: $800 million over seven deals. It appears that renewable energy is the only infrastructure sector gaining momentum. Most investors are tapping into opportunities created as a result of the Paris Climate Change Agreement, signed by 175 parties in 2015 to slow climate change.

“SWFs and other institutional investors have embraced new investment opportunities arising from the transition to a lower-carbon economy,” said Majed Al Romaithi, Executive Director of the Strategy and Planning Department of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), and Chair of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds.

“These range from infrastructure investments in solar and wind energy provision in both developed and emerging markets, through to early-stage venture-capital investments in new technologies in the battery and transport sectors,” added Al Romaithi when discussing the One Planet SWF Framework and the latest developments in measuring and reporting on climate change, in an interview with the IFSWF team.

It is not a surprise, therefore, that in 2018, two sovereign wealth funds – the China Investment Corporation (CIC) and Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation (APFC) – were part of a consortium that closed the largest renewable energy generation transaction in history. Global Infrastructure Partners, an infrastructure investment manager, and Canadian public pension fund, PSP Investments, led the $5 billion acquisition of renewable energy developer Equis Energy. The partners settled in cash, including assumed liabilities of $1.3 billion. It was an unusually large transaction for the sector, fully reflecting Equis Energy’s value as Asia-Pacific’s largest renewable energy producer.

Chart 1.2 SWF Direct Investments in infrastructure by sector

Source: IFSWF Database

Competition more than regulatory pressures slow down investors in infrastructure.

Headlines suggest that sovereign wealth funds and institutional investors are facing greater resistance from regulators preventing them from investing in major infrastructure assets abroad. Regulatory regimes in the US and Europe appear to have more stringent screening processes for foreign direct investments in strategic infrastructure assets. In the US, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury, which reviews any transaction that could threaten national security now has sweeping powers to stop deals in strategic sectors, and particularly in infrastructure. However, few transactions have ever been rejected outright by CFIUS, although from time to time parties have withdrawn from review and terminated those deals with the likelihood of an unsuccessful outcome.

Investors are wary about the timing under which CFIUS operates, and the fact that it is difficult to obtain an “advance” read from the Committee on any given transaction.

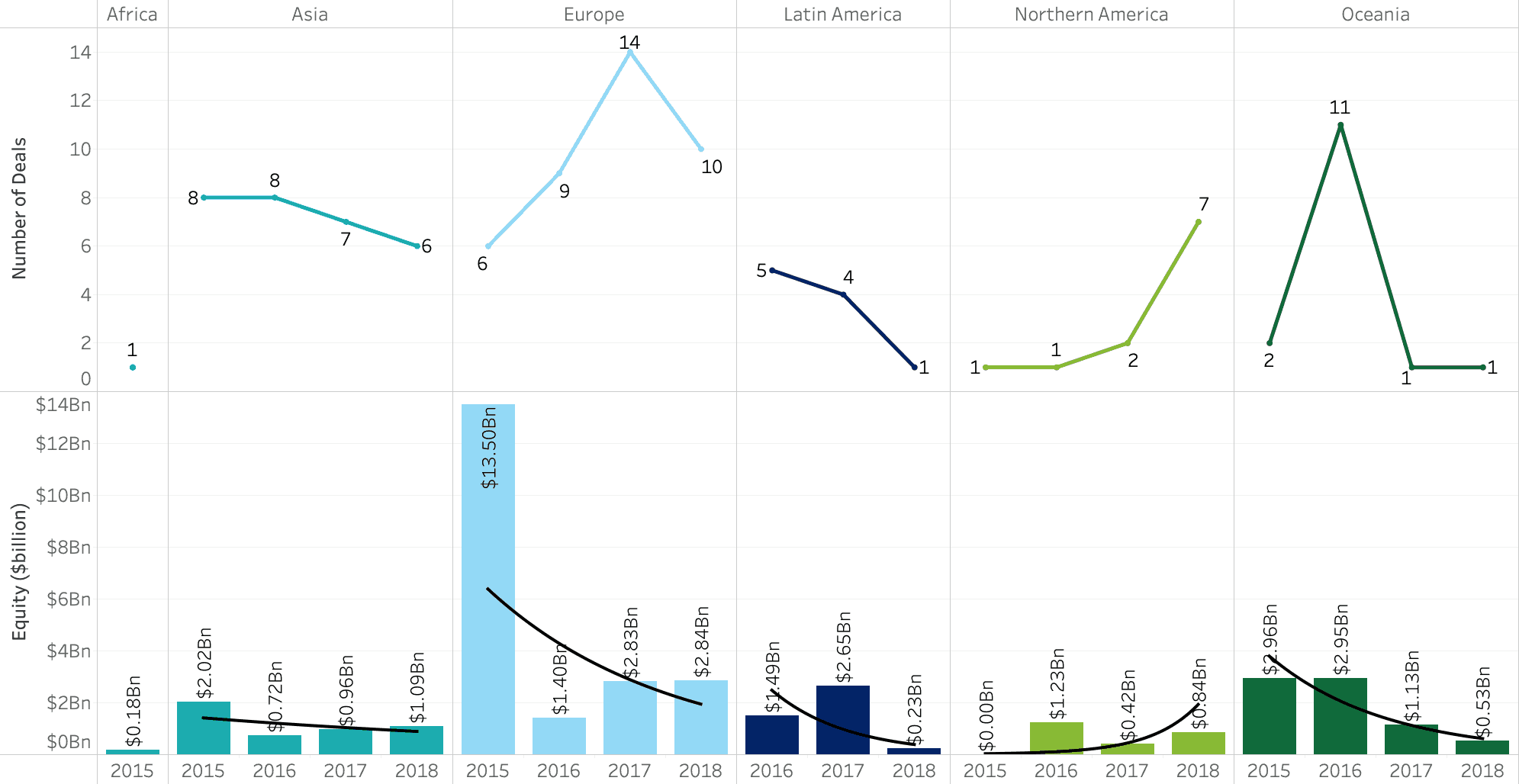

Chart 1.3 SWF Direct Investments in infrastructure by region

Source: IFSWF Database

According to our data, SWFs appear to be closing more deals in North America, despite the trade war rhetoric, more than tripling the number of deals from two in 2017 to seven in 2018. Europe, another difficult market, is still the largest region in the world for sovereign wealth fund direct infrastructure investments with 10 deals closed in 2018 for an equity commitment of approximately $3 billion.

Nonetheless, most of the infrastructure deals in Europe are facilitated as co-investments or joint-ventures with local sovereign development funds, such as the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) or the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund (ISIF). For example, in October 2018, RDIF and France’s water and sewage operator Veolia group, established a joint venture for investing in Russian utilities.

That said, when not operating as a magnet for co-investors in their domestic economies, government funds are facing increased competition and higher valuations for mature assets in developed markets. One developed market with a steady stream of privatising infrastructure assets like Australia, has been a case in point where major privatisation programmes have been hard fought. In 2018, the only sovereign wealth fund to invest in the country was ADIA, as part of a Transurban-led consortium (including Canada’s pension fund CPPIB and AustralianSuper) that purchased a 51% stake in Sydney’s new toll road development WestConnex for A$9.3 billion ($6.8 billion) from the New South Wales government.

Funds and co-investment partnerships promoting domestic development

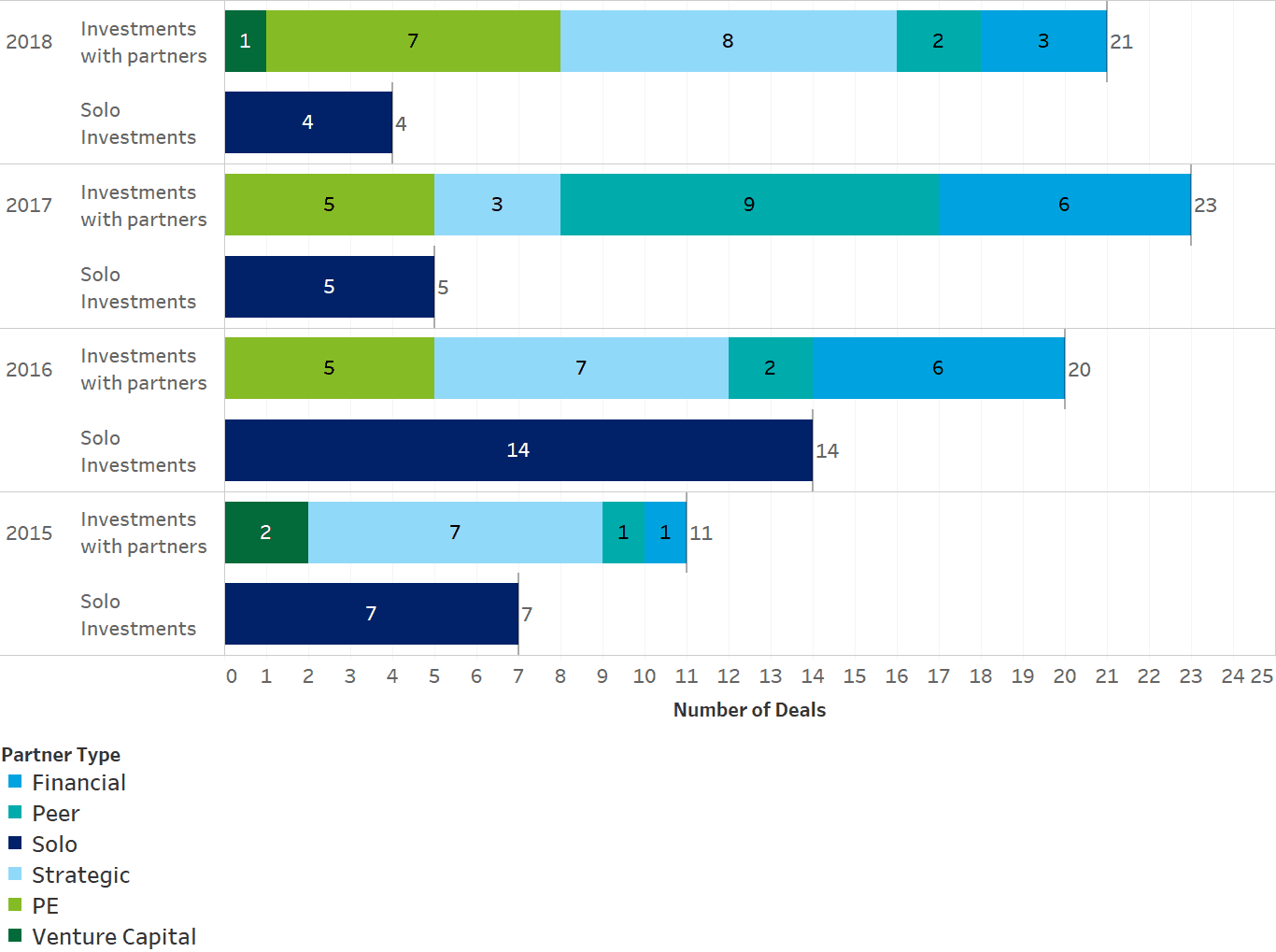

Over the last four years, SWFs have invested alongside a range of partners. In infrastructure, the trend accelerated in 2018, as SWFs completed 21 investments as part of consortia, over five times more than deals completed as solo investors in both public and private markets.

Chart 1.4 SWF Direct Investments in infrastructure by type of partner

Source: IFSWF Database

Although SWFs have been investing with peers and strategic investors for almost a decade, in 2018 they have found novel ways to collaborate with a range of partners. There is a consolidated trend towards SWFs partnering with other asset owners in both innovative new platforms and traditional private-equity-style transactions. In 2018, the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation, for example, made an additional investment of $20 million in Generate Capital, a sustainable energy financing company, in which it originally invested $100 million in 2017. The objective of Generate Capital is to partner with leading technology vendors and project developers to build, own, and operate infrastructure projects.

Private-equity and venture-capital managers are also benefiting from SWFs becoming more collaborative and were co-investors in a third of SWF infrastructure investments in 2018. That SWFs are becoming more collaborative is partly driven by the fact that they are looking for exposure to innovative industries, such as energy storage and transport in the infrastructure sector. In January 2018, for example, Singapore’s state investor Temasek Holdings joined a group of venture capital investors, led by Activate Capital in the $80 million Series D round of storage startup Stem. The Californian company creates innovative technology services that transform the distribution of energy, using a proprietary artificial intelligence system for energy storage and virtual power plants.

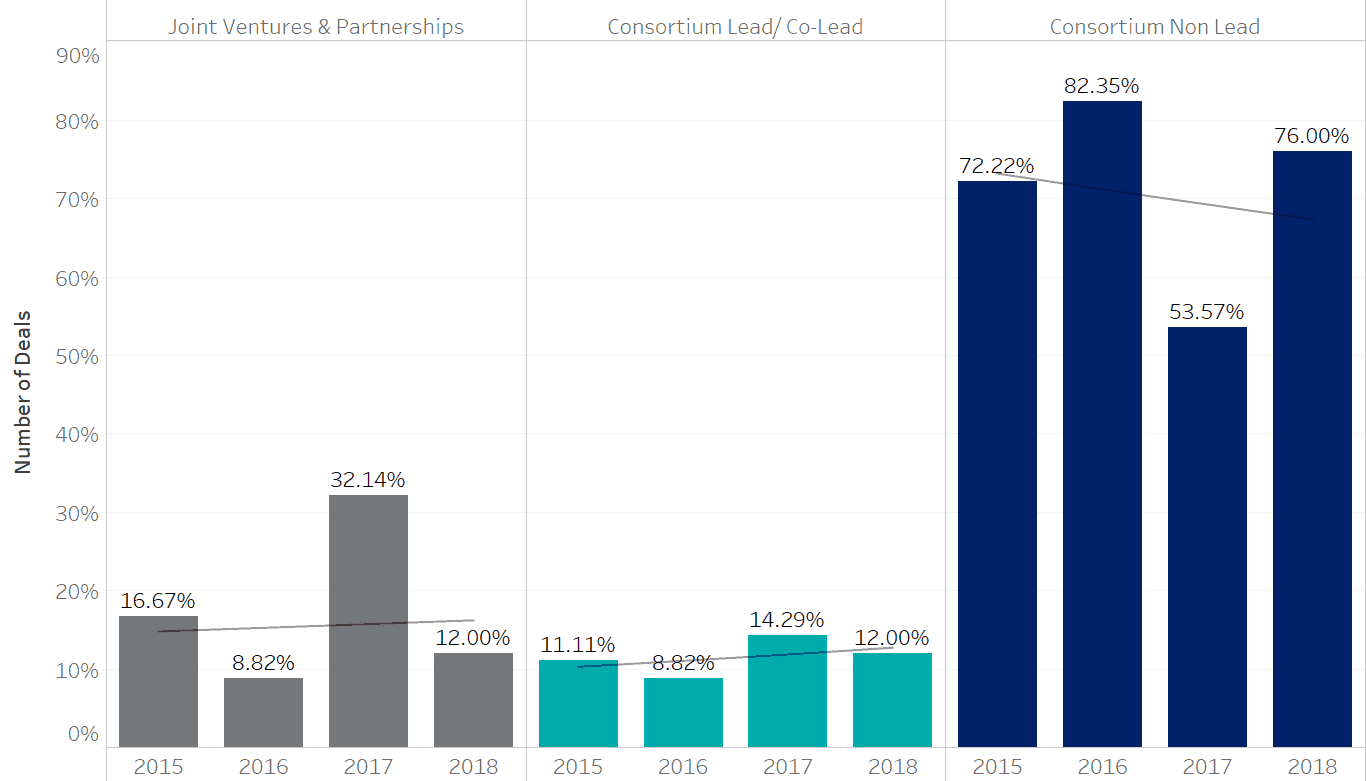

Chart 1.5: SWF Direct Investment type of partnerships in Infrastructure by % of total deals

Source: IFSWF Database

While SWFs are increasingly taking the lead in consortia in other sectors, infrastructure seems to be an exception. SWFs still need the expertise of asset managers or other infrastructure specialists: they completed 76 per cent of transactions in 2018 as a non-lead. This is despite strategic and development funds, such as the Russian Direct Investment Fund, Italy’s CDP Equity and Ireland’s ISIF, that have a specific remit to attract foreign direct investment generally act as lead investors.

Developed and emerging markets alike still struggle with an infrastructure gap. It appears that government funds are often the best-suited investors to partner but, even they still face significant hurdles. SWFs are struggling to source deals in infrastructure as the demand is much stronger than the supply, therefore they are relying on new ways of investing in the asset class, mainly accelerating early-stage investments in renewable technologies, and with novel partnerships and co-investment structures.

Enrico Soddu is head of data and analytics at the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds and Victoria Barbary is director of strategy and communications.