While data suggests that the ESG and impact investing markets are growing rapidly, concerns abound about how financial services firms are measuring and managing their ESG and impact investing performance.

Most performance is measured based on relative benchmarks, with success defined as performance being stronger than peers.

However, as a new report from the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) highlights, it seems impossible to even make incremental progress without measuring performance relative to planetary boundaries and social norms.

Moreover, measurement and management frameworks are primarily focused on portfolio company operations and ignore the role of investors, lenders, and underwriters, including the impacts of their own financial structures and practices. Yet these financial systems and structures can systemically undermine positive impacts at the enterprise level – and themselves contribute to ESG and financial risk.

The WBA report launches a scoping phase for a new initiative – the Financial System Transformation Benchmark – which aims to address these critical gaps. WBA invites stakeholders to engage and provide input.

The project specifies internationally defined goals such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Paris Agreement, and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and, through its proposed publicly accessible benchmark, “aims to present a clear image of how the world’s most influential financial institutions (asset owners, asset managers, banks, consultants and insurance companies) contribute – positively or negatively – to achieving the global goals.

At the core of this is the need for financial institutions to avoid and address the negative impacts associated with their activities. This initiative is critical because the benchmarking approach is intended to help incentivise ‘a race to the top’ among keystone financial institutions, “influencing systemic change towards the achievement of globally agreed sustainability goals.”

As we at the Predistribution Initiative (PDI) have emphasised in the past, Building Back Better and a sustainable economy cannot occur with responsible investment tools limited to the portfolio company level.

Prior to COVID-19, $5 to $7 trillion of annual investment was deemed necessary to address the SDGs. Post-COVID-19, these numbers are likely even higher. As one interviewee in the report notes, “Frankly, if more companies avoided harm through their operations, we would likely need fewer [investments that contribute to solutions that address identifiable social and environmental challenges].” We will never achieve the SDGs if we are consistently creating new negative impacts through the financial system and systematically undermining the positive impacts at the portfolio company level.

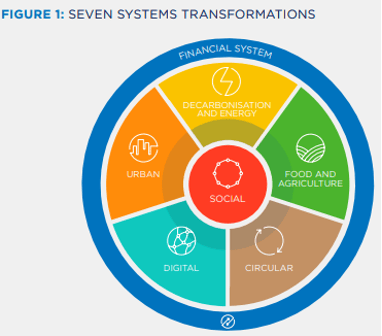

As illustrated in the below WBA diagram, the economy consists of both companies – that have impacts on other key ‘systems transformations’ critical to achieve the global goals – as well as the financial system that fuels it.

Building Back Better is thus a two-part equation, with accountability needed at both the portfolio company level, but also at the investor, lender, and underwriter levels.

For instance, we need measurement and management tools that can capture whether fund manager compensation exacerbates economic inequality, whether domiciling investment vehicles in tax havens depletes tax funding for essential public services, how excess leverage in capital structures can leave companies and their workers vulnerable, and how lobbying and political spend by the financial services sector can clash with stated ESG goals.

Indeed, the very fundamentals of finance may need deep evaluation and adjustments – most investments, financial performance, and therefore incentives, are evaluated based on time-value-of-money performance metrics, whereby finance professionals are motivated to make as much money back as fast as possible – a concept that seems inherently at odds with long-term sustainable investing and ESG integration. Valuation methodologies and incentive structures themselves may need to change.

The WBA Scoping Report highlights these systemic issues, stating, “The dual role of the financial system puts it in a unique position: it must undergo its own transformation while also operating as a vital enabler of the other six systems transformations.”

However, it is hard to change existing practices when we do not measure and manage them and their impacts. There is currently little accountability for the investor, lender, and insurer side of the equation. Thankfully, there are emerging initiatives, such as the Top1000funds.com Global Pension Transparency Benchmark (GPTB), which ranks 15 countries on public disclosures of key value generation elements for the five largest pension fund organisations within each country. The fact that the GPTB is the first global standard for pension disclosure highlights the need for new levels of analysis and accountability across the financial system.

WBA notes that, “Although some have complained about a proliferation of corporate sustainability disclosure initiatives, many financial institutions fail to hold themselves to uniform standards of disclosure. There are fewer frameworks for assessing the progress of financial institutions specifically, and hardly any for measuring progress that use the denominator of the global goals.”

Through its analysis, WBA finds only one initiative – the UNEP FI Positive Impact Tool – meets its five proposed criteria, enabling “a holistic materiality assessment of the impact on people and the planet across all SDGs. The remaining handful of initiatives that meet all five criteria are singularly focused on climate mitigation…”

Critically, a key goal of WBA’s benchmark is to, “encourage the acceleration in development and uptake of frameworks that can help close the gap in measuring performance against the global goals.”

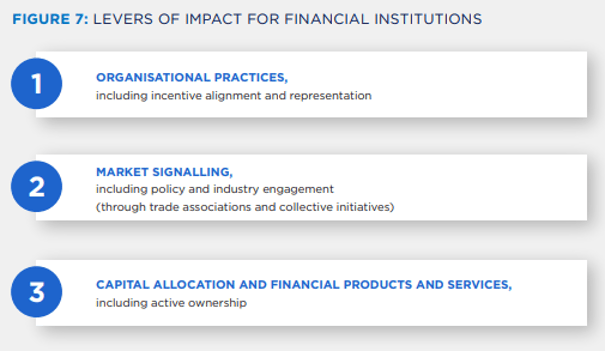

This emphasis comes from WBA itself being an Alliance, of over 200 public, private and civil society organisations (including Predistribution Initiative), so the project recognises that input from diverse stakeholders is imperative – including from actors in the financial system itself. It breaks down categories through which improvements can be made, as illustrated in the following diagram, and solicits feedback.

It is important for industry practitioners to participate, since the benchmark will impact them, and they are some of the best equipped in terms of knowledge and experience to help guide changes.

Moreover, collaboration with other stakeholders in shaping the benchmarks facilitates dialogue and understanding of other views and helps builds trust – another necessary ingredient to Building Back Better. Such interactions with diverse stakeholders also help investors stay ahead of the curve on “dynamic materiality.”

At the Predistribution Initiative, we are enthusiastic that WBA’s proposed benchmark will be part of the essential toolbox needed to start shifting the current paradigm from self-definitions of sustainability and towards sustainability in the true sense of the term.

Delilah Rothenberg is founder and executive director of the Predistribution Initiative.