The attempts by multiple Republican states to restrict where US pension funds can invest is symptomatic of bad governance. Top1000funds.com takes a deep dive into the quagmire of US state pension funds to assess the impact of partisan politics on the ability of CIOs to do their jobs. The analysis highlights the need for improved practices around delegated authority to prevent the politicisation of investments.

So much has been written about the rise and fall of ESG investing. But as an active participant in the global investment industry, and a non-American, it is extraordinary to observe the grandstanding efforts by US politicians, collapsing their vote-grabbing job functions with their roles as stewards of long-term capital.

The obvious and stark mismatch between the two-year political cycle and the long-term nature of pension investing is at the core of this problem, which also highlights the ignorance of the politically elected in managing pension assets. It’s no wonder best-practice pension management is complicated and difficult to attain.

The convoluted governance structures of US state pension funds, where elected officials are also trustees of the pension money and in some cases the sole trustee, is the complicating issue. And according to some governance experts, it’s the source of the problem.

The anti-ESG movement has been played out through comical headlines and quotes, one example being Montana’s Attorney General Austin Knudsen: “Montana’s a northern state. It gets really, really cold. We can’t heat our homes with rainbows and fairy dust.” But the impact is being felt by the investment staff whose jobs are to maximise the best financial outcomes for the beneficiaries of the pension funds whose money they manage.

The now-famous Montana letter, signed by 21 state Attorneys General and sent to 53 of America’s largest fund managers and financial institutions, argues that the investment industry is following liberal principles of woke capitalism for illegitimate reasons and contravention of fiduciary duty.

According to Roger Urwin, one of the world’s leading investment governance experts, their fundamental thesis is a strawman fallacy.

“It is the knocking down of an investment thesis that hasn’t been put forward in the first place,” he says. “But it is symptomatic of something we should respect in the investment industry that is that the politicisation of investments has become a systemic risk.”

The biggest risk is the legitimacy of the pension fund mission.

Shooting a moving target

The problem with the investment industry arguing either side of the ESG war is the fight is not about investments.

“My problem with the ESG wars is it’s like looking into the sun, that’s how stupid it is,” says David Wood, senior researcher at the Social Innovation and Change Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School, who has educated many pension fund trustees through the Initiative for Responsible Investment at the Kennedy School.

“My problem with the ESG wars is it’s like

looking into the sun, that’s how stupid it is.”

“What is the point of talking about the ESG wars as an investment style when it’s not what has motivated the attack?” Wood says.

It can be difficult to understand the arguments. One example of the complexities is in the state of Oklahoma which according to US Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm is already the fourth-largest generator of renewable energy of all the 50 US states, with enough wind, solar, and energy storage capacity to power all of the state’s households, two times over. While it’s traditionally been a big fossil fuel state, clearly clean energy is a big part of its future.

And yet last month the state’s treasurer put together a list of 13 financial institutions that are prohibited from doing business with the state for engaging in “boycotts of fossil fuel companies” claiming the firms, including JP Morgan and BlackRock, were “beholden to social goals that override their fiduciary duties”. Both firms claimed the treasurer’s claims were baseless and their business practices were “not anti-free market” as claimed.

By nature, politics is short term and pension investment is long term. Investment professionals at the helm of pension investment management are managing 40+ year financial liabilities to an accuracy of three decimal points. Exploring the complexity of how these two competing time horizons intertwine is difficult and complex.

A Journal of Finance paper, Political representation and governance: evidence from the investment decisions of public pension funds, found that pension funds whose boards contain greater representation of state officials underperform. It explores three sources of poor decision-making by those state officials: control, corruption and confusion. Among other things, the paper says elected officials may be more inclined towards opportunistic behaviour arising from personal career concerns or the desire to attract political contributions.

This is certainly the observation from many investment professionals Top1000funds.com spoke to for this article, who noted that the behaviour of the political-elected trustees on their state pension fund boards did not even consider beneficiaries’ interests as an afterthought.

Many US public pension funds conduct their board meetings in public arenas. San Francisco City, for example, has public comment after every agenda item at its board meeting, and many public funds hire multiple lawyers just to deal with the Freedom of Information Act requests.

Many US public pension funds conduct their board meetings in public arenas. San Francisco City, for example, has public comment after every agenda item at its board meeting, and many public funds hire multiple lawyers just to deal with the Freedom of Information Act requests.

There are many problems with this structure, not least of which is focus. It opens the arena to people with objectives at odds with the beneficiaries and distracts trustee focus. When a trustee is also an elected official it can veer even more off course.

“Politics and investment don’t mix,” says Craig Slaughter, CEO and CIO of the $19 billion West Virginia Investment Management Board (IMB), a position he has held for three decades.

He believes recent legislation introduced by West Virginia’s Republican administration to claw back direct control of the fund’s proxy vote marks the tip of an iceberg. Political interference in investment decision-making threatens the fiduciary independence of the retirement plan, he says. [See: West Virginia CIO fears anti-ESG campaign threatens fiduciary duty]

The new legislation, coming into force in the next 15 months, will increase the level of scrutiny and impose potentially costly processes and hurdles in the proxy voting process. However, Slaughter’s main concern is that this legislation marks the first step on a road that could see the legislature tell the pension fund how to invest its assets.

One day that could mean ordering divestment of fossil fuels by those that oppose investing in them, but right now he is more concerned the anti-ESG movement led by West Virginia’s cultural Republicans could start to dictate investment strategy that could include forcing investment in West Virginia’s fossil fuel industry.

“At the IMB we don’t favour or disfavour fossil fuels, we just buy them if they are a good investment and if not, we don’t; but that may no longer be good enough. Whether pro-ESG or anti-ESG, the idea of using other peoples’ money to achieve a political purpose is offensive to me.”

“Whether pro-ESG or anti-ESG, the idea of using other peoples’ money to achieve a political purpose is offensive to me.”

The political hurly-burly is impacting state pension fund CIOs’ day jobs in a meaningful way.

“From an investment perspective I’m trying to use every tool I can to make better investment decisions – any other CIO will say the same thing,” says Andrew Palmer, CIO of the $63 billion Maryland State Retirement and Pension System. “Politicians are taking the ESG bat and hitting each other with it. And that has made the life of people trying to make investment decisions more difficult.”

“It turns out good risk management is important for banks; that is a governance thing. If you don’t have good safety for petroleum companies, there can be multiple-year impediments for that company. Every fundamental investor I know looks at these issues to make better decisions. That’s ESG. If CIOs think they can make more money by looking at ESG factors they will look at it,” he says.

Chris Ailman, the long-time CIO of CalSTRS has been dealing with external pressures on investments for more than 25 years.

“The average teacher works for 30 years and lives for another 30 after that so this money has a 30- to 60-year time horizon. When you think that long-term you think of all sorts of things beyond the balance sheet. You need a lot more information,” he says. “Whatever initials you want to use, these are long-term risks, and they should be disclosed by companies so we can make investment decisions. End of discussion. This is not about political outlook it’s an investment decision. I’ve never thought of them as political, and still don’t. But I am saddened by fact that people characterise words and suddenly make them good or bad.”

Indeed, Willis Towers Watson’s Roger Urwin says asset owners worldwide are trying to solve a financial equation, not solve something more pro-social or pro-environmental. And yet it’s become a political issue.

The governance conundrum

To understand best practice pension governance, it’s necessary to go back to 1980s Canada, where independence from the United Kingdom was fresh and KD Lang’s career was going gangbusters.

In 1986, Keith Ambachtsheer was on a taskforce set up by the then-Treasurer of Ontario, Bob Nixon, to reform pension organisations. The resulting report “In whose interest?” recommended two ways public sector pension management could be improved: first, ensure pension deals were intergenerationally fair; and second, that arm’s-length pension organisations should be governed and managed as effective financial intermediaries with fiduciary mindsets.

“If you are going to create a great pension system there has to be legitimacy and value for money. Governance is critical to both. You have to understand what arm’s-length means, and you have to understand good business to be effective,” Ambachtsheer says, adding clear delegated investment authority is a key feature.

The outcome of the report, and the implementation of the governance principles it outlined, was the formation of Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan which has returned more than 10 per cent a year since inception.

The outcome of the report, and the implementation of the governance principles it outlined, was the formation of Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan which has returned more than 10 per cent a year since inception.

“It can be done right,” Ambachtsheer, a Canadian himself, says. “I look south of the border and shake my head. There are a few US states that have people who understand the principles around what Peter Drucker said and create outcomes that are kind of OK, but they are a [clear] minority. The issue is at odds with the original principles of legitimacy and effectiveness.”

Similarly, Willis Towers Watson’s Roger Urwin has spent his career advising asset owners on governance and organisational issues – notably Australia’s Future Fund and New Zealand Super, both recognised for their organisational acumen.

He is working with USS and Sweden’s AP funds, and although he did some work with the CalPERS’ board some years ago setting up their investment beliefs, he has done limited recent work with US funds. Urwin, whose work with Oxford’s Gordon Clark demonstrated there is a 100 to 200 basis points a year return attributable to good governance, says there are three universal rules of governance: pension funds are fiduciaries; they should be independent; and they should be run as professional organisations.

“Those three principles take you a long way,” Urwin says. “It looks on the surface in the US as if both the fiduciary and independence principles are being challenged in some funds.

“The fiduciary-duty principle has always started with a financial-first orientation, but essentially sustainability is one of the instruments to secure the financial mandate,” Urwin says. “Sustainability is instrumental to financial outcome. But not everything in sustainability is supportive to financial outcomes. Understanding where those things are inter-related is important.”

In the US there are some examples of good governance and Utah’s John Skjervem, for example, cites the fund’s governance model as a critical support for his team’s decision making.

Specifically, the URS board addresses investment matters in executive sessions which limit the “political grandstanding and virtue signalling” that Skjervem says is commonplace at many US public-plan board meetings.

Skjervem says the URS governance shields the entire program from politics and “non-fiduciary” influences, allowing the team to focus exclusively on hunting for the best risk-adjusted returns without interruption or interference. He believes this combination of delegated investment authority and multi-level fiduciary oversight is the program’s “secret sauce” and manifests as excellence in both portfolio construction and team culture. [See: Utah Retirement Systems: Why ESG is a waste of time]

But Utah is a rare case, and for the most part the governance of the state pension funds is complicated at best, embroiled in the political sphere.

“Politicians shouldn’t get involved in the investment policies in pension plans that are properly set up at all,” says Amabachtsheer. “As soon as they put their fingers in, they are offside. One of the big breakthroughs in the Canadian model was that politicians are deathly afraid to meddle – and they should be.”

“Politicians shouldn’t get involved in the investment policies in pension plans that are properly set up at all.”

According to Ambachtsheer, turning retirement savings into wealth-producing capital is the narrative that is central to pension fund management.

“The whole question should be what is the best way for pension funds to do that transformation process?” he says. “OTPP got that straight away. It forces a long horizon, and you understand the businesses you are investing in. If you are a knowledgeable investor, then of course you can call up those companies and ask them about what they are doing. It comes naturally if you have the right narrative. In the US there are some cases where funds have gone off road on that central narrative to a laughable extent.”

If getting the foundational governance right wasn’t hard enough, now investment practice is moving from 2D investing with a focus on risk and return, to 3D which also incorporates real world impact.

“It’s going to get more messy,” Urwin says.

The Thinking Ahead Institute, which Urwin co-founded, encourages investors to look through a systemic lens incorporating social, technological, economic, environmental, political, legal and ethical issues which all have influences on the system in which investments operate.

“The new phenomenon is the increased connectedness of these things which is speeding up change as well as increasing complexity,” Urwin says.

Rob Bauer, Professor of Finance at Maastricht University has been studying ESG considerations for more than 20 years and agrees where societal issues and financial institutions there is complexity. He believes a lack of authenticity from product providers has added to the polarisation and politicisation of ESG issues in the US.

“I needed 20 years to understand what we are talking about here, every day a piece of the puzzle is added,” he says. “Then suddenly these marketing organisations come through overnight and say they are experts on ESG.”

“I needed 20 years to understand what we are talking about here, every day a piece of the puzzle is added. Then suddenly these marketing organisations come through overnight and say they are experts on ESG.”

The most complicated governance relationships according to Bauer are where the boards delegate their proxy voting to firms such as BlackRock and Vanguard.

“These organisations have commercial incentives, that are often conflicting. On one hand BlackRock is saying divest, but on the other hand Texas oil companies are clients of BlackRock. This says it all. How can these organisations engage when they have two different stances?”

For Maastricht’s Bauer, who also advises many Dutch funds on ESG-related issues, it again comes back to governance.

“Pension organisations set up investment beliefs and hire organisations to implement. But it’s more like they are wishing for an outcome so they set up beliefs consistent with that. But they have to test the beliefs regularly,” he says. “ESG is a container so broad and complicated, how do you measure preferences?”

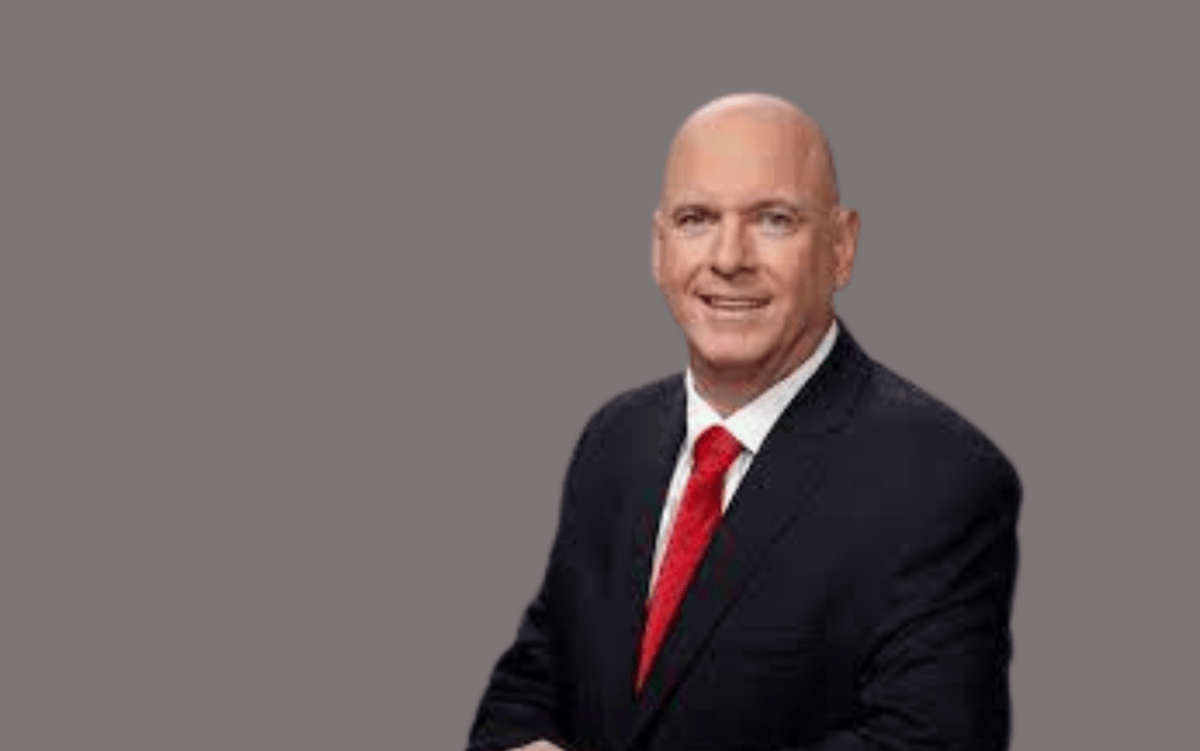

Anger over proxy votes

To get a sense of the level of grievance red-state investors feel about the misuse of their proxy vote, we spoke to to South Carolina State Treasurer Curtis Loftis, beginning his fourth term as sole trustee of the state’s $65 billion fund, the bulk of which is invested in a $41 billion portfolio and separate from the state’s $38.2 billion pension fund which is managed by the Retirement System Investment Commission (RSIC). Loftis insists asset managers fired the opening shots in the now-raging ESG war by misusing institutional investors proxy votes in the first place.

Most of his anger is directed towards BlackRock, which was mandated to run a passive equity allocation in the state’s portfolio until Loftis began removing BlackRock mandates, most recently re-allocating a final $200 million tranche to Vanguard.

Most of his anger is directed towards BlackRock, which was mandated to run a passive equity allocation in the state’s portfolio until Loftis began removing BlackRock mandates, most recently re-allocating a final $200 million tranche to Vanguard.

BlackRock was using South Carolina’s proxy to mandate dramatic changes in energy use, employment practices and looking after stakeholder rather than shareholder interests and that didn’t represent the beliefs of the people of South Carolina, he says.

“We’ve eradicated them from our portfolio,” he told Top1000funds.com. “BlackRock was voting contrary to our wishes. It’s as if I couldn’t vote and asked my best friend to vote Republican for me, but he voted Democrat, sealed it up and mailed it.”

Loftis, who was retired for 10 years before he returned to work to take up the role as South Carolina’s banker, managing, investing, and retaining custody of the state’s assets, continues. “This is what happened on a massive scale and it’s appalling, and it fuels the conundrum we are now in today. It’s about getting these asset managers to vote the investment dollars we’ve given them in accordance with the beliefs of the people who own them.”

“It’s as if I couldn’t vote and asked my best friend to vote Republican for me, but he voted Democrat.”

Talking to Loftis reveals that taking back control of the proxy voting process is being driven by a deeper grievance than just a belief that the vote was being used contrary to South Carolina’s Republican taxpayers’ beliefs. He believes ESG-minded proxy voting has infiltrated corporate America and is now triggering fundamental change for the worse. Take the gradual move away from shareholder to stakeholder primacy for example. In today’s new world of stakeholder capitalism, companies are beholden to their community, consumers, and special interest groups not just shareholders, yet he believes these groups shouldn’t be a company’s responsibility. “We have governments to keep stakeholders happy,” he says. “It’s tipping the financial house of America on its head in a process that hasn’t been sanctioned at the ballot box.”

Loftis says the capital markets used to work well. Now a business wanting to raise money must comply with ESG and other non financial stipulations laid down by ratings agencies and banks that insist on a swathe of rules that do not represent conservative ideas.

“It is difficult to raise capital if you don’t have a high ESG score,” he says, describing a new landscape where corporate America, a reliable conservative partner, is now in the grip of “a hard left ideology”.

Perhaps the fact that ESG isn’t the result of a democratic process – and wouldn’t, he says, pass through Congress if presented – angers him most.

Perhaps the fact that ESG isn’t the result of a democratic process – and wouldn’t, he says, pass through Congress if presented – angers him most.

“ESG is changing a country and culture but without having the government permission to do so,” he says. “It’s created a veneer of governance that we don’t think is even legal.”

The guardians of South Carolina’s pension assets managed by RSIC are also preparing for change. The ESG Pension Protection Act, passing through South Carolina’s legislative process and which Loftis expects to be ratified either this year or next, would require the retirement system consider only “pecuniary factors” when making investment decisions. Although this is consistent with the perspective RSIC currently takes when managing the portfolio, the bill also requires the state’s retirement system to exercise shareholder proxy rights for shares that are owned directly or indirectly on behalf of the system.

Negotiations over the bill have required substantial involvement by chief executive of RSIC Michael Hitchcock.

“I’ve spent a significant portion of my time over the past year working with the legislators on ESG legislation,” he says.

A process during which, like other CIOs interviewed by Top1000funds.com, he articulated his biggest fear is an outcome that decreases the availability of investment opportunities in a way that impacts returns and leads to increased contributions. HIs goal has been to keep the focus on RSIC’s obligation to earn an investment return that helps fund benefit payments for the retirement system’s 600,000 beneficiaries.

“We are not woke, or anti-woke,” he says. “We are anti-broke.”

CIOS hitting back

Florida’s Republican Governor and US Presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis, the anti-ESG camp’s biggest hitter, has signed into law a bill that prohibits and seeks to punish all ESG considerations in the state’s investment decision-making, spanning all state treasury and retirement plan funds. It requires Florida State Board of Administration, guardian of $232.5 billion including the $181 billion Florida Retirement System, to only make investments on pecuniary factors and prohibits, amongst a raft of other restrictions, banks integrating ESG factors into their lending criteria.

DeSantis said the legislation would protect “hard working pensioners” against “woke” asset managers and “joyriding ideology” and said he believes Florida’s legislation, which follows on from Florida State Board of Administration divesting the state’s pension investments from BlackRock, will act as a blueprint for other states opposed to ESG, in a multi-state effort.

DeSantis said the legislation would protect “hard working pensioners” against “woke” asset managers and “joyriding ideology” and said he believes Florida’s legislation, which follows on from Florida State Board of Administration divesting the state’s pension investments from BlackRock, will act as a blueprint for other states opposed to ESG, in a multi-state effort.

“This governor is leading the fight and 20 other states are following his lead into battle,” says Florida’s chief financial officer Jimmy Patronis, who sits on the SBA board alongside DeSantis and Attorney General Ashley Moody as the three government-elected trustees.

But the idea that Florida’s sweeping legislation, backed by the campaign’s biggest beasts, signposts the rollout of similar legislation at other pension funds is not necessarily the case. CIOs are also hitting back.

Like Alan Conroy executive director of $24.3 billion Kansas Public Employees Retirement System, whose testimony highlighting the potential impact on the pension fund contributed to legislators reducing the scope of Kansas’ Protection of Pensions and Businesses Against Ideological Interference Act. The final legislation still restricts ESG but addresses all concerns Conroy raised in testimony. Like the fact forced divestment from ESG-minded managers, restructuring the portfolio and hiring new managers could cost $3.6 billion over the next decade, impacting the already underfunded pension system. He warned that KPERS’s funded ratio could be lowered by 10 per cent due to the combined impact of lost assets due to divestment and increased liabilities due to lower future investment.

Forced divestment from ESG-minded managers, restructuring the portfolio and hiring new managers could cost $3.6 billion over the next decade,

Other CIOs also complain if anti-ESG legislation in their states went through in its original format it would have a huge adverse impact on their investment organisations, including needing to fire managers, build bigger internal organisations or go passive – all of which have cost, resource and return implications.

CIOs are also arguing that new proxy rules create an unnecessary layer of administrative complexity in structures that are already highly bureaucratic compared to global peers, that will make them less competitive with private market investments.

“These requirements could also prevent the system from using commingled investment accounts that often provide a more efficient, low-cost way of investing trust fund assets,” KPERS’ Conroy told legislators. He also sounded a warning bell on new complexities around the term “fiduciary”.

It’s a similar story in Nebraska, where Michael Walden-Newman, CIO at $40 billion Nebraska Investment Council has resisted an attempt by Nebraska state legislator to introduce legislation banning ESG investment that directly interfered with fiduciary duty.

“I explained to legislators that Nebraska already states that the investment council is prohibited from making any investment if its primary purpose is for social or economic development benefit,” said Walden-Newman. “Also, that the members of the investment council board and I, as CIO, are fiduciaries under the law, and are bound by that fiduciary responsibility to ensure investments are made for the benefit of the members of the various retirement plans and the general taxpayers of Nebraska. The Legislature chose to not act on the legislation.”

In Texas, where an anti-ESG bill went through the legislative process earlier this year but was not passed because it missed a key deadline, Amy Bishop the executive director of the $45 billion Texas County & District Retirement System (TCDRS) raised similar concerns with the Senate State Affairs Committee. She warned the proposed bill would impact the organisation’s “ability to maximize returns and have a financial impact on employers” adding the bill would keep the fund from “partnering with some of the best investment managers in the world”. She warned that adjusting the asset allocation could cost more than $6 billion over the next 10 years, causing employer contributions to double.

How do you right the ship?

The governance structures of US public plans were set up in the 1970s and are due for modernisation.

55 per cent of the board members of US public sector pension funds are either appointed through some kind of election process or through ‘ex-officio’ status, requiring board membership by state or local officials. The number in Canadian and European pension funds is zero per cent.

The important distinction, according to CalSTRS’ Ailman, is that these organisations are trusts set up for a specific benefit.

“These are trust funds and they needed to be treated that way. We don’t use that word enough and that’s why we’ve lost sight of it,” he says.

“These are trust funds and they needed to be treated that way. We don’t use that word enough and that’s why we’ve lost sight of it,” he says.

“Seeing trust funds being attacked by both sides of the aisle may be enough of a catalyst for us to make some change. These retirement plans are for multiple generations. I have 20-year-old teachers starting this fall and it’s their pension too. Elected officials want to make a statement and so why not use somebody else’s money? It’s too easy for them.” CIOs and their investment teams are money managers trapped inside the business model of a government entity.

“These are trust funds and they needed to be treated that way. We don’t use that word enough and that’s why we’ve lost sight of it.”

“That is costing us money,” Ailman says. “But even that is not enough to make people want to change the governance, because the people who will change it are the ones using it for personal gain. I can’t put my finger on what will cause it to change, but when it does it will spread like wildfire across the country.”