Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, marks the 15th anniversary of its Singapore office this year, with the unit now firmly established as its Asia-Pacific stronghold. With regional growth set to continue in the coming decade, NBIM is well-positioned to capitalise on it, says Singapore head Sumer Dewan.

NBIM closed its Shanghai office in 2023, citing a pivot to the garden city as the regional trading hub, and shut the Tokyo real estate office in May due to the small portfolio sizes it managed.

Dewan has been with the Singapore office for most of its journey and says the offshoot was set up to be a “mini-NBIM” from day one, housing departments from portfolio management to technology and operations.

“The office is very fit for purpose for that long-term strategy that we have for the region,” he tells Top1000funds.com in an interview.

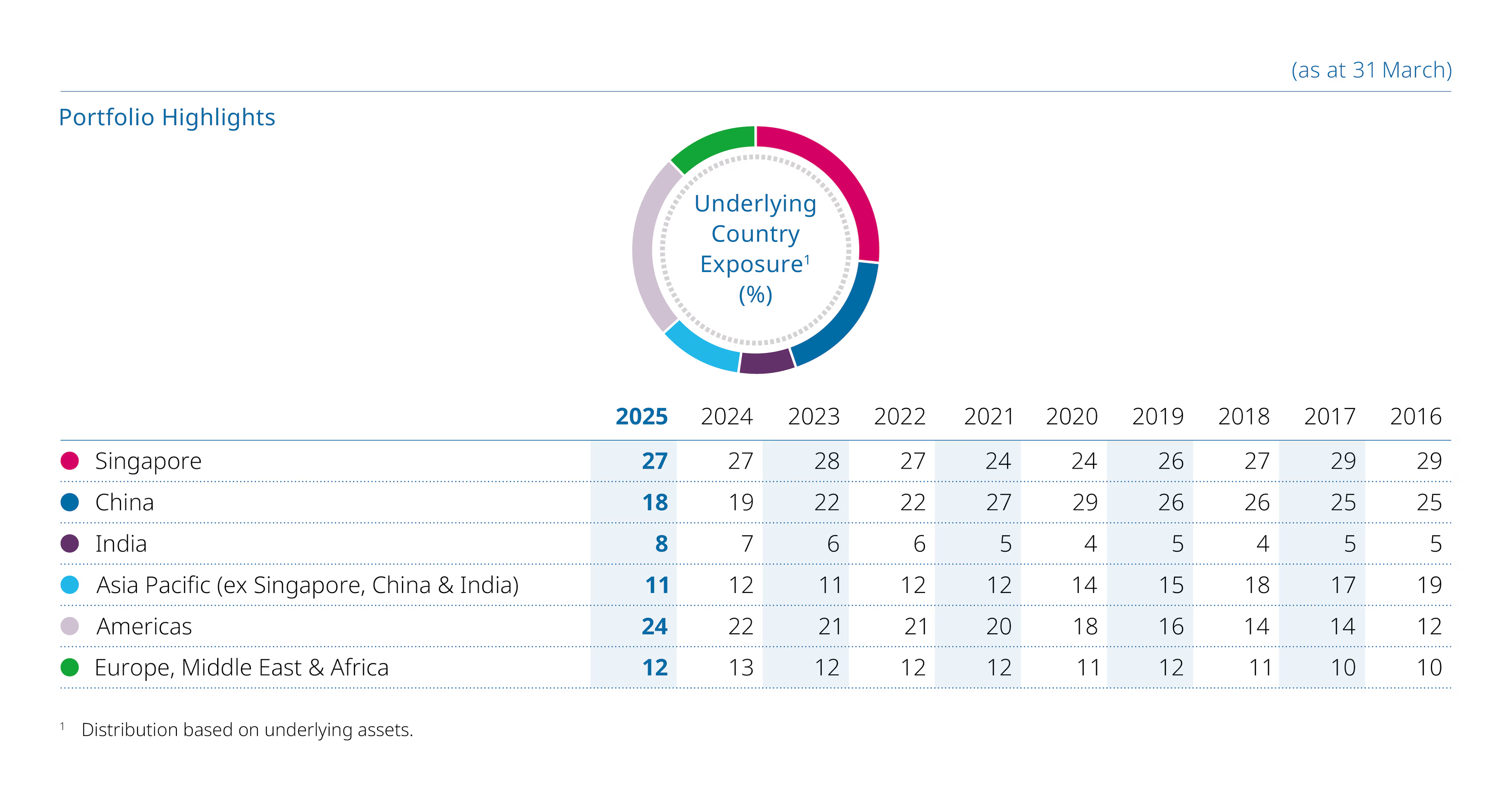

The fund has a strong focus on Asia and invests 4.6 per cent of its massive equities portfolio in Japan – its second biggest market after the US – while China (2.2 per cent), India (1.7 per cent) and Taiwan (1.7 per cent) were also among the top 10 countries, according to its 2024 annual report.

It also has the most individual holdings in Asia including 4,391 companies, compared with 1,901 in North America, 1,546 in Europe and 821 for the rest of the world.

NBIM’s Asia exposure is largely driven by the index due to the fund’s substantial passive exposure, but there are some active decisions made by its internal stock-pickers, known as sector portfolio managers, and to some extent the index portfolio managers.

“Index portfolio managers may choose to go over or under[weight] certain companies based on the research that they’re doing,” Dewan said.

“It is more opportunity based. … maybe there’s some relative value trades that didn’t exist some years ago, but now we see a difference. For example, the same stock in different regions – mining stocks in Australia versus the same mining stock in the UK. As the situation arises, we certainly are positioned to take advantage of that.”

The biggest edge of the local office is enabling NBIM to make high-level decisions in Asia-Pacific time zones without having to seek approval from global headquarters like many of its peers, Dewan says. The fund trades around the clock with coverage from its Singapore, Oslo, London, and New York offices.

“The fund has much interest to maintain that reputation as really being the preeminent call on the street when there are situations, either liquidity situations or otherwise. Being here live definitely is an edge,” he says.

“But also the setup is an edge. With one client account, it makes it transacting very streamlined. The operation’s processes are very easy compared to some of our peers who have hundreds of different kinds of accounts.”

The Asia-Pacific markets are having their moment in the sun again as investors seek to reinvest some of their US assets elsewhere to manage Trump-related risks. Japan and Australia have emerged as attractive developed markets alternatives, and the promises of a stellar growth story in India have also drawn substantial capital flow.

While NBIM does not have plans to reduce its US allocation, Dewan says it sees diverse opportunities in Asia.

“Each one of these [countries in Asia] provides its own set of opportunities that we are very much involved in.”

Trade conflicts are not a new investment risk in Asia but Dewan says the lack of decisions and clear rules of doing business right now have asset owners like itself worried.

Some 15 countries, including Japan and South Korea, are still negotiating with the US on tariffs as the July 8 deadline for completing trade talks approaches.

“I think that overhang is putting some sand in the machinery,” he says.

“If we can get clarity to the rules of the road, whatever they might be, I think then the region will be 100 per cent adjusted to that. There’s a history of that.

“We have found the Singapore ecosystem very helpful to us. In addition to the obvious reasons why people are here in terms of the governance and rule of law, we’ve been able to hire very well here,” he says.

“If we look ahead, I would imagine a lot more investors [coming to Asia]. I would hope a lot more investors do.”