Megatrends are the forces that will shape our planet, our society and our lives decades into the future. The Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Stanford University heard megatrends provide potentially rich pickings for investors, as long as they know how to use them, and how to start looking for the best opportunities.

Investing is all about making as well informed and accurate predictions as possible about the future directions of nations, economies, markets and securities. And delegates at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Stanford University heard that one of the most reliable investment indicators are so-called megatrends.

Pictet Asset Management senior investment manager and head of thematic equities Hans Peter Portner said megatrends are necessarily forward-looking, as opposed to benchmarks which by their nature are backward-looking, and they have three essential characteristics.

“First of all, they are long-term, they have a life expectancy of at least 15 years,” he said. “Then they are very deep and broad – broad, as they impact governments, they impact enterprises, they impact our personal lives; deep, as they change how we run governments, they change how we do business and they change we conduct our lives.”

Portner said a megatrend is made up of smaller trends that come together to form a forward-looking big-picture view. Pictet builds on the work of the Copenhagen Institute for Future Studies in identifying the megatrends it uses to begin its research.

“Megatrends conceptually are an aggregation, a complex aggregation, of trends, of sub-trends and fads,” he said.

“The way I depict it is you can imagine it as a river fed by streams and creeks and trickles.

“The investment concept behind all this [is that] where mega trends intersect, themes emerge.”

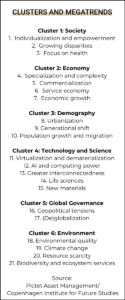

Portner said Pictet has identified 21 megatrends, collected into six major clusters (see box), but it is up to individual investors to determine which of them they believe are most significant, where they intersect, and hence which are potentially investable.

Delegates at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium nominated Technology and Science: AI and computing power (nominated by 73 per cent of delegates), Environment: Climate change (55 per cent), and Technology and Science: Life sciences (23 per cent) as the three most investable megatrends.

Delegates at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium nominated Technology and Science: AI and computing power (nominated by 73 per cent of delegates), Environment: Climate change (55 per cent), and Technology and Science: Life sciences (23 per cent) as the three most investable megatrends.

Once identified, the intersection or convergence of megatrends give investors an indication of where to begin looking for potential investment targets. But Portner stressed that while megatrends may provide a starting point, the onus remains on investors to do due diligence and deep company analysis to find the best investee companies.

“Megatrends are your friends,” Portner said.

“And the megatrend gives you the focus with these intersections. It is the starting point of your company analysis. You screen for companies that have a high exposure to the secular trends. And if you are a long-term investor, extremely focused, you’re also strategic partners to the management teams you invest in.

“So we are we are extremely active in engagement to extract further value. Our themes have also natural exposure to environmental and societal variables. So we are also impactful. This is a very big theme in in Europe, probably less so still in the US, but is certainly also coming.”

Portner said successfully investing in megatrends requires the right ecosystem of academic research to define the megatrends; investment professionals to conduct the analysis to find the companies likely to benefit most from those megatrends; and industry practitioners who can monitor the trends going forward.

“You need the infrastructure,” he said.

“You need to create the right ecosystem. And you need some academic input. You need some raw material. These sources are sociologists, people looking to the future. You find them, you find think tanks that offer this. And then you need, obviously, PMs who look at intersections. That’s our value-added, we create intersections of mega trends.

“And then as when themes emerge, they are not static. Megatrends remain stable, these are really, really steady things with a life expectancy of 15 years, as I’ve already said, but themes evolve over time.

“And that’s why we have also for each strategy an advisory board attached, composed of professors from universities dealing with the themes we are active on. We have independent analysts [and] we have CEOs of companies that are part of this segment of the market.”