Migros-Pensionskasse (MPK) the CHF29.4 billion ($31 billion) pension fund for Switzerland’s largest retailer, Migros, is in a robust state of health. A coverage ratio of 132.8 per cent means chief investment officer Stephan Bereuter is comfortably taking on more risk via a boosted equity allocation, and last December MPK was able to increase its pay out to beneficiaries.

“We paid an additional 2000 francs to every pensioner. We’ve got letters from people saying how much it meant to them,” he tells Top1000funds.com in an an interview from MPK’s Zurich offices.

Bereuter, who was promoted to CIO in 2022 after a year at the fund which he joined from head of asset management at insurance group Generali, attributes much of the success to internal management (90 per cent of the fund is managed internally) and a dynamic top down/bottom up investment strategy that allows the investment team to buy and sell assets outside the strategic asset allocation in a reactive and flexible approach to opportunities.

Like in May 2023 when MPK invested in insurance-linked securities in an allocation that is not part of MPK’s SAA.

The asset class had struggled since 2017 and by 2022 many investors had thrown in the towel and divested. But it was at this point Bereuter saw the opportunity.

“Spreads had risen and become very high for the risk investors were taking. We were being well compensated and decided to allocate,” he recalls.

Even recent storms in the US haven’t negatively impacted the portfolio which returned 16.5 per cent last year, underscoring the robust attachment point and structure of the investment.

Still, a large part of the return is driven by the long-term strategy, adjusted in an ALM study every four years and an area Bereuter is most focused today. He is increasing the equity allocation via small tweaks to 30 per cent (from 28 per cent) via small tweaks to the portfolio, and boosting the allocation to gold to 3 per cent.

MPK’s equity allocation is below average compared to peers and he believes that in the long run equities will perform well.

“From a strategic point of view, it makes sense to increase equities,” he says.

But the strategy is also indicative of a new caution in US tech stocks that has driven returns for passive investors. Now the boosted allocation will comprise a new, internally managed 3 per cent sleeve that shifts away from US tech stocks to focus instead on companies that have a strong dividend yield and stocks with strong balance sheets and cash flows rather than a pure value approach.

“I don’t think many managers who make active decisions could have outperformed a benchmark portfolio because performance was driven by such few stocks. But we now hope the dividend approach will add diversification, and not be as dominated by tech stocks.”

Gold’s appeal

MPK’s allocation to gold sits with custodian banks and holds compelling fundamental and liquidity benefits.

The precious metal has steadily climbed due to central bank buying, inflation and geopolitical tension and Bereuter also likes the allocation as a hedge against increasingly concerning government debt levels. He argues that even though interest rates are higher, central banks are still in a phase of expansive monetary policy in an ongoing monetary experiment.

“Central Banks have printed so much money in the last decade and Switzerland is a world champion in this regard.”

Given 39 per cent of assets under management are in illiquid allocations to infrastructure and real estate, gold also provides valuable liquidity benefits alongside a cash portfolio and super-high quality issuers. But he says even government bonds have proved illiquid in recent years.

“During Covid government bonds had liquidity issues, but gold didn’t behave the same way. We need gold to provide a bucket of liquidity in stress scenarios.”

Timing real estate

Corners of MPK’s 9 per cent allocation to international real estate are also beginning to show signs of recovery. For example, after three years in the doldrums, he notices core real estate is beginning to re-price to create pockets of value.

“We are in a position to allocate money again,” he says, hoping the team’s experience in actively managing the portfolio will once again pay off.

Successful divestment of the core international allocation to more opportunistic, externally managed strategies in early 2022 on the eve of core being clobbered by lower cap rates and a spike in inflation and interest rates that left many investors struggling to exit was timed perfectly.

“We are now looking at core real estate again. Cap rates have gone up and you can get nice returns moving forward.”

He is still not keen on office but likes data centres and notices opportunities beginning to appear in residential and logistics – although he is also mindful of an economic downturn hitting logistics. “There is over supply in some pockets already.”

Despite the hot money flowing into data centres he believes returns look solid because it is still early in the cycle, although he does favour projects in the near future with clear visibility “It’s not too late to play this investment,” he says.

The internally managed allocation to Swiss real estate accounts for 24 per cent of the total portfolio and he describes the allocation as the “backbone” of the pension’s stable income returns of above 3 per cent. It is a senior portfolio characterised by long term ownership in strong locations that is now benefiting from rent increases. The portfolio returned 2.5 per cent, 4.80 per cent and 5.7 per cent for its 1-, 3-, and 5-year return, as of September 2024.

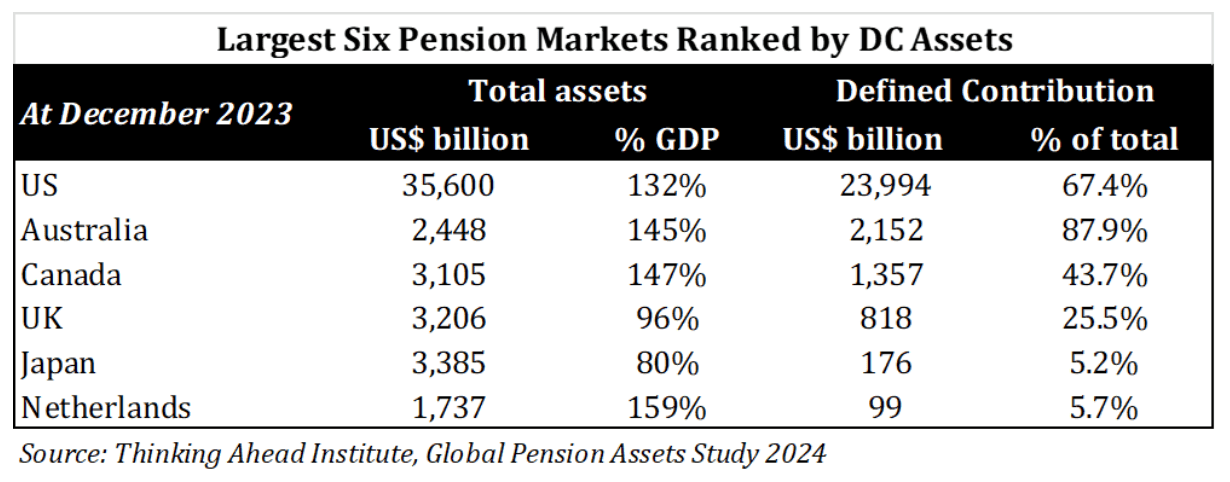

Our broad-ranging report considered the benefits, risks and issues arising from big super. The overall conclusion is that Australia’s super system is a boon. It has facilitated the creation of a large pot of retirement savings that is being professionally managed, and brings benefits related to improved stewardship of capital and broadening out of available funding sources in the economy.

Our broad-ranging report considered the benefits, risks and issues arising from big super. The overall conclusion is that Australia’s super system is a boon. It has facilitated the creation of a large pot of retirement savings that is being professionally managed, and brings benefits related to improved stewardship of capital and broadening out of available funding sources in the economy.