Is chasing the Canadian model of a large allocation to illiquid assets appropriate for every pension fund? It’s a question that the £34 billion multi-client asset owner Railpen has been investigating in research that examined the right target allocation to illiquid assets in the context of risk tolerance, flexibility and liquidity management.

“This is something we have wrestled with for a while,” head of investment strategy and research John Greaves says.

“Parking the strategic merits of investing in illiquid assets, we wanted to investigate our client’s liquidity capacity, or risk tolerance related to their allocation to illiquid assets, across private equity, private debt, infrastructure, real estate and other alternative illiquid assets.”

According to Greaves the most important thing in setting the limits on long-term illiquid asset allocation is the “portfolio steerability” which includes understanding the clients’ need for flexibility.

“Every investor has a tolerance for the portfolio to drift over time away from a strategic asset allocation,” he says.

“Illiquid asset classes tend to have smoothed and lagged asset valuations which can amplify this effect.”

Led by Lukas Vaiciulis, research by the strategy team – which will publish a working paper later this year – resulted in a framework that focused on scenario planning and the uncertainty inherent in illiquid investments.

Greaves says the allocation to illiquid assets has typically been approached by investors in a heuristic manner, with allocations determined by what “feels right”. A research literature review didn’t reveal much quantifiable research and yet it is one of the most important decisions that investors make.

“It is something you can plan for and think about what happens and what you would do under different scenarios,” Greaves says. “I was really keen we approach this in an open-minded way. I asked the team to tell me why we can’t do the Canadian model.”

Railpen’s scenario planning focused on the problem of over-allocation and the inability to get back to target in a reasonable timeframe or to deploy in favourable market conditions.

“We looked at the allocation drift and what the options were to rebalance, including secondary market transactions” Greaves said, in an interview in the fund’s Liverpool Street, London, office.

The impact on short-term liquidity management was also considered. “Typically, short-term liquidity risk is managed by maintaining a prudent level of cash-like assets against an extremely stressed cashflow scenario. However, the issues come when you need to recapitalise. What assets are you selling? What if the stress gets worse over the following months? We found these issues interacted with the illiquid assets, but it was only limiting at very high levels of illiquid assets given our cashflow profile and liquid asset mix.”

Uncertainty and lagged performance

The Railpen modelling also looked at the uncertainty of returns and cashflows and the impact of lagged returns and smoothing.

“We wanted to have a framework where we recognise the uncertainty with illiquid asset cashflows and can test different allocations against our risk appetite and make sure we are able to do what is needed for our clients in certain environments,” Greaves says.

A framework was developed that tested a number of scenarios including changing the strategic allocation without undermining the investment case of the investments.

“Investors allocate to long-term illiquid investments because it is bringing something to the overall portfolio, like additional return or diversification, and we need to hold the assets for a reasonable period of time to realise those benefits, it takes time to play out,” Greaves says.

“From a portfolio construction perspective, if you need to sell at the wrong time, it might undermine the reason for the investment in the first place. I think it is a common myth that you can just sell certain direct investments when you need to. There is typically an investment thesis that plays out over many years and of course large costs to buy and sell,” he says. “We want to try and avoid having to sell assets before we would like to or being unable to deploy in favourable market conditions, where possible.”

Testing the portfolio against various scenarios while being able to maintain investment discipline resulted in an allocation to illiquid assets for defined benefit (DB) schemes open to new members of around 30-40 per cent, much smaller than the allocations seen by the Canadian funds which in many cases is 60-70 per cent of the portfolio. This highlights the importance of recognising and understanding client-unique objectives, constraints, and opportunity sets in choosing the right investment strategy.

“We found when we go above a 40 per cent allocation to illiquid assets, we start to see a lot of drift, forced sales and big changes in the amount we can deploy each year, particularly in a scenario where the target changes” Greaves says.

The open DB pension schemes that Railpen manages are slightly cashflow-negative which also impacts the illiquid allocation.

“Cashflow positive funds can go higher,” Greaves says.

Flexibility, agility and change in processes

The research also looked at allowing for the target allocation to change through time. Flexibility is important if the belief is the right strategy for an open DB fund can change over time in response to market conditions and funding.

“We do think flexibility is important and we wanted to test the ability to change our mind in the future,” Greaves says.

“The results were somewhat non-contentious, but the exercise gave us some quantitative rigour and gave us some confidence. If the board says our mandate will never change then that’s different. Some funds like sovereign wealth funds perhaps have a more stable mandate.”

Railpen found the illiquid asset mix was also very important. “If we have more in direct, cashflow generative assets like infrastructure, or shorter-duration assets like private credit, then we could push it higher,” Greaves says. “Like anything in investing you look at your risk tolerance, investment beliefs, and where you can add value. This research helped us find our sweet spot at this time.”

The exercise resulted in the fund changing its approach to private asset allocations, reinforcing the idea of being proactive, adjusting pacing quite frequently.

“While private assets are a long-term investment it is not a set and forget,” Greaves says.

One of the practical changes in the process is the strategy team now regularly meets with the illiquid teams to talk about pacing.

The research was also a useful tool to talk to the board about the importance of flexibility and demonstrate different scenarios including one example which was reducing the illiquid assets from 40 to 20 per cent over five years.

“They got comfort that we demonstrated we can move from a relatively high allocation to something much lower in a short period of time through the cashflow profile of the assets, even in a shock or stressed environment” Greaves says.

Now the fund looks at its illiquid allocations in the context of the role the asset plays, the exit and the execution, in a dynamic approach. All Railpen investments are modelled with a cashflow profile and exit periods under different scenarios, with those assumptions kept up to date.

“In illiquid assets, the execution is so important,” Greaves says. “We are trying to think about the exit upfront and keeping the analysis up to date.”

The exercise also showed the importance of maintaining good market relationships with external managers, trying to maintain a good pace of investment with the best managers where possible. The impact on internal teams was also a consideration.

“Institutional investing is much more than just a good strategy. It’s the whole institutional investing ecosystem on how you deliver on that well”, he says.

“By thinking about these decisions through the lens of the overall institutional investment process, we believe it allows schemes like ours to better respond to client needs.”

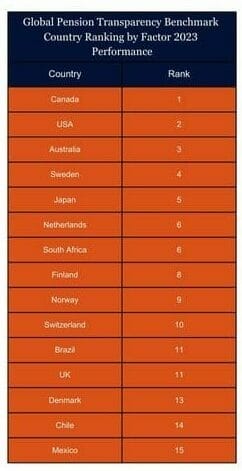

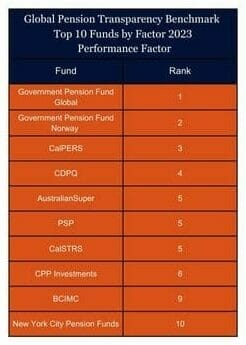

The GPTB does not account for different regulatory regimes, but it acknowledges that different regulators are driving different disclosure requirements that could impact fund disclosures and comparability.

The GPTB does not account for different regulatory regimes, but it acknowledges that different regulators are driving different disclosure requirements that could impact fund disclosures and comparability.

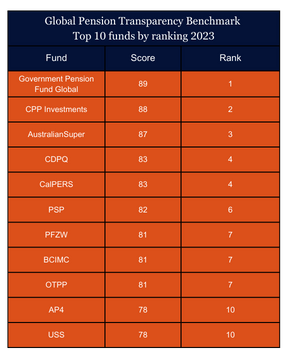

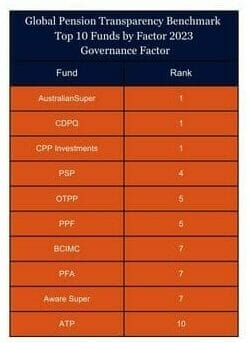

they want to be better. This year there has been more discussion about the importance of transparency and the benchmark has driven change and put a line on best practice.”

they want to be better. This year there has been more discussion about the importance of transparency and the benchmark has driven change and put a line on best practice.”

CEM’s Heuberger notes that funds were more likely to provide quantification of their responsible investing initiatives and this year, and that more funds went a step further and provided context by laying out longer-term goals.

CEM’s Heuberger notes that funds were more likely to provide quantification of their responsible investing initiatives and this year, and that more funds went a step further and provided context by laying out longer-term goals.