Asset owners and managers may not always agree on fees, but one thing both parties are thinking a lot more about these days is creating innovative structures which – if done right – could provide rewards for the former and value for the latter.

Albourne Partners head of fintech and implementation Gaurav Amin said fees shape what a manager or an investor does from both an economic and behavioral standpoint. Albourne is a non-discretionary alternatives investment consultant.

Amin told the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Oxford that one economic impact of fees is on investment strategy.

“One of the big things which is going on right now is multi strategy managers who are using pass-through fee structures, effectively charging 7, 8, 9, or 10 per cent management fees,” Amin said.

“For them to earn that level of fee, or to justify that level of fee, what we have calculated is they need to be a third more levered than any other multi-strategy manager delivering the same level of return.

“Your investment strategy is being directly driven by the fee structure that you have.”

Behaviorally, fees influence how much risk managers take, and also impact the team-building and the culture of a manager organisation, which asset owners should consider when they are looking for long-term investment partners.

Amin said one of the common reasons why managers ask for high fees is to attract talent, but asset owners need to consider how the fee is distributed within the organisation.

“[Managers say] ‘talent is very expensive nowadays, and that’s why we want to create the higher fees.’ However, a team is more important than the collection of stars,” he said.

“How the bonuses are given out is quite important and drives the culture of the company. So, if you’re looking for a sustainable investment…that you are willing to live with for a long period of time, then having the right fee structure within the company itself can be quite important.”

Amin urged asset owners to consider the “three gripes” of fees when negotiating the next mandate with managers. The first one is the level of fees.

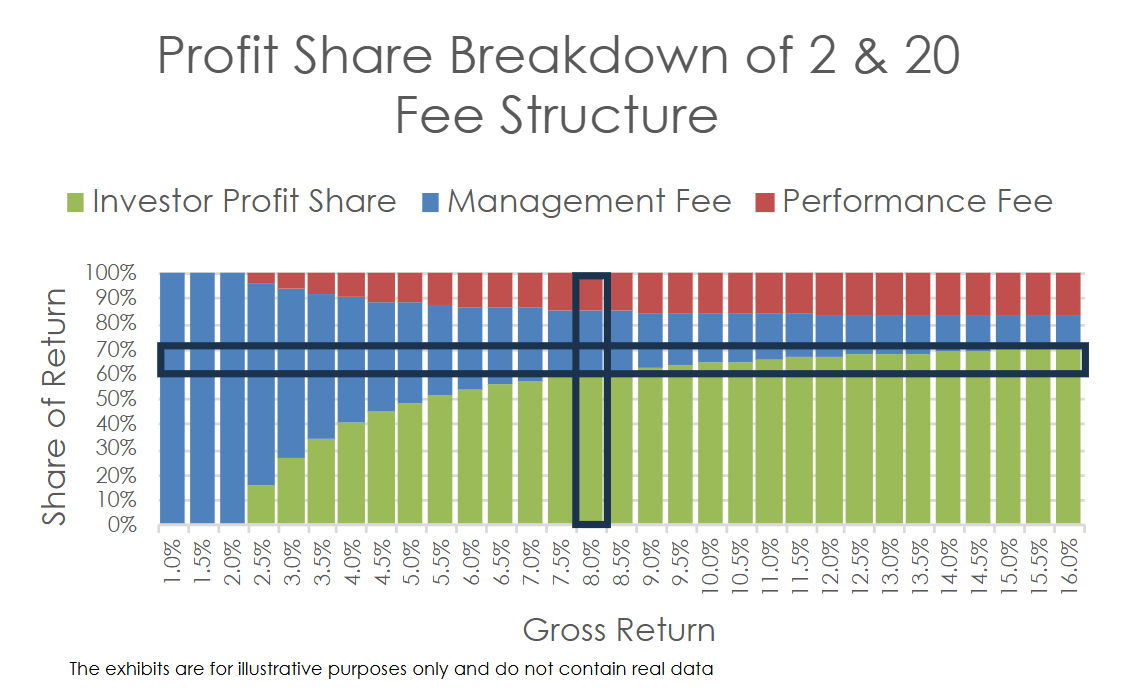

The problem with traditional fee models such as a 2-and-20 structure is that there is an imbalanced investor profit share. Albourne’s analysis shows there is likely to be an equilibrium of fees when investors’ share of profit reaches 60 to 70 per cent – below that range, investors may deem investment in a fund unworthy; higher than that range, managers may not be sufficiently incentivised. The level of fees is hence critical, because there is always the likelihood that investors will lose patience before it reaches equilibrium, Amin said.

The second gripe is the shape of the fee structure, where there are more nuanced opportunities for asset owners and managers to align their goals, Amin said.

The second gripe is the shape of the fee structure, where there are more nuanced opportunities for asset owners and managers to align their goals, Amin said.

For example, if asset owners are investing in a fund to provide a hedge, then there should be higher management fees and lower performance fees. If it’s a pure alpha fund, then asset owners should seek a higher performance fee and lower management fees.

The shape of the fee structure is also where investors can get creative with incentives for different types of managers. With hedge funds, there are levers such as high watermarks, crystallisation periods, and hurdles; for private market funds there are things such as carried interest, catch ups, and monitoring fees.

Amin reminded managers that “one fee structure is not going to solve all your problems”.

“Each investment – each investor – in the same fund could have a different objective, and therefore they have a different fee structure. So, it is up to the manager to offer those,” he said.

“That will help align the interest of that particular investor.”

With that said, however, no fee solution should come at the expense of the last gripe of fees, which is transparency. It is notable that different variables and structures often make fees difficult to measure and benchmark.

Amin said there might be a bigger role for consolidated metrics such as investor profit share (IPS) to play in fee measurement. He defined IPS as share of gross returns that the investor earns or is expected to earn for a given fee structure.

“This is where transparency comes in: how is the manager managing the money? And how much transparency are they giving you? Are they making those decisions for the fee structure or for the performance?” he said.

“That’s the collaboration that you need to have with your manager, to have that constant dialog saying, ‘you are doing these things for the right reason or the wrong reason’.”

Institutional investors strive to link their strategic asset allocation to their key objectives and ensure it evolves alongside technological advancements. A discussion at Fiduciary Investors Symposium Oxford explored the complexities and trade-offs inherent in portfolio construction.

At the C$25 billion Canadian pension fund OPTrust, the portfolio is tailored to meet liability and funding commitments alongside returns, and risk mitigation. The investor has a total portfolio approach and views risk and liquidity as scarce resources. Elsewhere, the public allocation is dynamically managed and includes a currency management approach at a total fund level.

The illiquid allocation adds another level of complexity, particularly given that at any time, total fund-level risk is deployed. OPTrust actively manages its private market exposure where investments include private equity and real estate, said Jacky Chen, managing director, completion portfolios, total portfolio management.

Railpen, the multi-client pension fund for the United Kingdom’s rail industry is open and growing, and its strategy is keenly focused on asset valuations and cash flows. A key priority for John Greaves, director of fiduciary management, is to understand the objectives and preferences of trustees. Asset management is approached with the view that both public and private markets are exposed to the economy and shouldn’t be viewed in silos: although real assets operate on a different cycle, they are still blown by the same winds as public market investments.

The analysis extends beyond just risk-return and correlation to integrate different scenarios. For example, what if illiquid investments don’t distribute much? This will result in a need for higher cash flows, alongside careful analysis of any over-allocation to illiquid investments.

Governance is focused on ensuring the team can manage the portfolio through time with an eye on resilience, liquidity, complexity and sustainability that goes beyond just risk and return.

The team also explore trade-offs. For example, real assets might not offer as high a return as other assets, but they bring valuable diversification and inflation protection and can also support sustainability.

“It is about finding the right balance,” said Greaves.

Adam Petryk, chief executive of solutions at Franklin Templeton, counselled on the importance of integrating qualitative and quantitative factors. Pension funds must first think about their diverse range of clients, understanding their differences in liquidity premia and risk appetite.

“Start first with the client need,” he said, highlighting the importance of using proxy assets to ensure a better-informed risk perspective.

Border to Coast, an LGPS pool in the UK, provides its underlying local authority pension fund clients with investment choices, offering a detailed proposition in private debt and infrastructure, amongst other assets. Its offering is balanced by the experience and knowledge of the right investment models amongst the skilled investment team.

More work in benchmarking

Joe McDonnell, CIO at Border to Coast, explained how the asset manager is selling public markets, buying private markets and moving more into alternatives. Conversations with partner funds include the importance of benefiting from long-term secular trends like climate investment and investing more in the UK.

McDonnell said one area of ongoing work includes benchmarking and measuring success. He noted that building out internal capabilities includes ensuring the fund has the right tools and learns from best practices.

“We are confident we are moving in the right direction,” he said. “Private markets for us is hugely important as a long-term investor.”

McDonnell noted that other LGPS pools need to catch up with pooling assets and allocating to illiquid investments, and called the government’s move to mega funds a positive development for the LGPS. However, he also recognised the need for leadership in the LGPS and that board turnover is high.

Petryk agreed that measuring success in achieving outcomes and gauging the success of the team and investment strategies remains one of investors’ biggest challenges. Articulating the investment value proposition through the lens of outcomes requires consideration of what investors are trying to achieve and the integration of peer benchmarks. The process is complicated by the fact that end investors are individuals who don’t measure you “against the S&P.”

Chen said that OPTrust is focused on managing the portfolio more dynamically to achieve long-term value and noted the importance of aligning incentives. In public markets, the team are responsible for beating the benchmark and trying to make sure they manage returns and drawdown risk.

Some of the team focus on portfolio construction and others focus on security selection. The process also allows them to work together to manage asset allocation and execution, and manage the portfolio dynamically on a day-to-day basis.

Chen referenced the importance of going into assets at different times in the cycle, and warned that investment in buckets risks missing out on opportunities. OPTrust is currently exploring the right governance to support a better understanding of assets through a factor lens rather than an asset bucket silo.

Railpen’s Greaves also reflected on the importance of alignment between investment decisions and ultimate goals. For example, the capital markets group at Railpen has an inflation-plus return target that is challenged when inflation spikes. Like Chen, he reflected that a top-down strategy to fill buckets doesn’t reflect changes in opportunities, and things fall between the gaps, requiring the team to meet their investment objectives “in different places.”

He noted how many investors are currently experiencing the impact of being over-allocated to illiquid investments. They have made decisions that risk undermining their long-term objectives and the benefits that these assets can bring.

“Think through the scenarios,” he warned.

McDonnell spoke about the importance of moving away from a culture characterised by investment teams talking their own book by championing preparation and consistency instead. In alternatives, teams often fight for the same space, but success involves thinking through why a particular decision makes sense. “It is about your own book and the wider book of the pension fund,” he said.

Panellists reflected on the importance of liquidity, a constant constraint that forces schemes to think about the trade-off and put a liquidity premium on valuations. It’s possible to have a situation where investors think they are delivering a risk-adjusted return but are, in fact, loading on the same type of risk.

The blue bond market can provide an innovative means of supporting the critically underfunded ‘blue economy’ and offer a compelling opportunity in fixed income with untapped impact potential.

Speaking at the Fiduciary Investors Symposium at Oxford, Matt Lawton, portfolio manager of fixed income, T. Rowe Price, said he observes a shift in appetite amongst asset owners to integrate ESG via blue bonds. He added that the nascent market offers investors first mover advantage.

Martin Dasek, senior regional climate finance lead and climate advisory expert at IFC Financial Institutions Group, said that blue bond investments are increasingly on investors’ radar. Blue investments are global and touch huge populations working across the marine ecosystem. They don’t just funnel capital into the oceans, but include fresh water and inland water where pollution like sewage and plastics begin their journey to the sea. He noted that blue investments are particularly impactful in Asia given the continent’s proximity to the sea and many sea-dependent economies.

Panellists reflected on the growth of the green bond market to signpost the potential growth in blue bonds. Like blue bonds today, green bonds were not regulated and market awareness was poor in the beginning.

Investors and asset managers like T. Rowe Price at the vanguard of the asset class have a role in providing regulatory support and partnering with key stakeholders. This includes providing guidelines for clients and investors that outline what the underlying asset looks like including metrics and KPIs.

The IFC’s Guidelines for Blue Finance provides a globally accepted template for blue finance, informing the investment industry on what classifies as blue to prevent blue washing. The IFC offers an advisory arm that is able to work with clients ranging from corporates to financial institutions to create sustainable frameworks that kick-start issuance

Lawton explained that T. Rowe Price is also seeking to build capacity in the blue bond market. This involves speaking to corporate issuers in emerging markets and encouraging them to originate and bring out new transactions. The asset manager is also working with bankers to try and bring out those transactions.

Risk and returns

Lawton explained that because the focus is on emerging market corporates, issuers typically have a low BBB credit rating. Typically, blue bonds have a 3-4 year duration profile and the investments have an attractive Sharpe ratio.

Another advantage is that in highly volatile markets these bonds outperform and trade more defensively because they are held by long-term investors: investors should think about allocating to blue bonds as a defensive long-term allocation that they hold through bouts of volatility.

Comparisons between a blue bond and a conventional bond issued by the same company show that blue bonds trade with an enhanced yield. They also trade with less liquidity and investors are paid a premium for holding that illiquidity. Panellists said that this illiquidity will likely compress over time as more supply comes into the market.

Investors in blue bonds focus most on the credit risk of the issuer. Returns are not dependent on cash flows coming in from the projects that blue bonds finance, and fundamental underwriting is crucial.

By going out first to emerging market corporates, T. Rowe Price is able to hand-select issuers and projects and find the most compelling impact.

Panellists noted that measuring returns is challenging because of the limited universe of blue bonds. However, this is starting to change. Blue bonds are also appearing in developed markets with issuance visible amongst shipping groups and sovereigns where investors can combine impact and return. Other industries entering the picture include the chemical sector and sustainable tourism, sea transport and port logistics. Investments in these areas will require deep and robust frameworks to ensure impact and development are delivered.

The panel stressed the importance of ensuring alignment between investors and issuers between impact and the financial return. Investors often say they don’t have a “shelf” to place the investment. But investors already have fixed income portfolios that have the same yield and credit rating – and a bit less US exposure.

The blue economy desperately needs funding to support and sustain the existential role it plays in all our lives. But investors are not putting their capital to work in the sector. To date, SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) and SDG 14 (life below water) have realised just 5 per cent and 1 per cent of total SDG funding, respectively, in an alarming shortfall given water’s uniquely fundamental role.

Meanwhile, oceans produce 50 per cent of the oxygen on earth and absorb emissions.

Ian Goldin, professor of globalisation and development, senior fellow at the Oxford Martin School and professorial fellow at the Balliol College, University of Oxford, sketched an emerging world characterised by a rising Asia and a declining West.

At the Fiduciary Investors Symposium in Oxford, he said the aging population in Western economies will spend more on services, productivity growth will slow, and investment as a share of GDP will fall. These economies are still struggling with the legacy of the GFC and the pandemic, and high levels of debt mean they are fiscally constrained. Worryingly, investment is slowing down just as economies need it most.

In contrast, Asia and the Gulf have high rates of growth and investment, creating a virtuous circle that makes politics easier. In this environment, it’s possible for governments to “give without taking”, making it easier to be a politician. In contrast, when growth is low it is only possible for politicians to give by taking. It’s why politics in the US and Europe has become more fraught.

These governments are under pressure to renew key assets like their energy, transport, defence and medical systems. Meanwhile, education systems need to adapt to teach new skills.

“The rates of investment are too low,” Goldin said in an opening keynote for the symposium.

He flagged a shortfall of investment across the public and private sectors as well as a shortage in the “software” of ideas, business processes and skills. He said that regulatory systems are also out of date.

“The world is accelerating and our understanding is lagging further behind. We are not investing enough in keeping up to speed.”

In Europe’s fractious political environment, decision-making has become increasingly complex. Not only do governments not invest because they “don’t have any money”, but they also profoundly disagree because they are focused on short-term re-election. He warned of the inflationary impact and harm to the US economy if Trump delivers on his promise to export undocumented workers and hike tariffs.

Turning to global demographics, Goldin warned that today’s plunging birth rates mean fewer people will come into the workforce in 18-year’s time. The collapse in fertility has impacted “half the countries in the world” including countries like India where the birth rate has fallen below the replacement age.

He linked falling birth rates to women’s right to choose, contraception, and the cost of living, leaving more people deciding not to have children. This is despite many governments around the world trying to encourage women to have more children, like France, which has spent €1 million per additional child on its policy. Goldin said no policies are particularly successful, and all are very costly.

As birth rates fall, people are living longer as medicine advances. New drugs like weight loss drugs, as well as cures for cancers will mean that we no longer worry about the same illnesses. However, people will continue to succumb to neuro-divergent illnesses, and Goldin said the rollout of medicines that cure mental health is slower. This means societies will increasingly be made up of highly dependent, mentally fragile but physically capable people sustained by a smaller workforce.

When modern pension systems were built, they were designed for an average life expectancy after retirement of seven years. Now the average life expectancy after retirement is 25 years. Meanwhile, real risk-adjusted returns for pension funds are much lower. Moreover, rapidly aging populations become more politically powerful accounting for a larger share of the vote in democracies. These people typically don’t want to do anything that interferes with their lives like building houses in their neighbourhood – or agreeing to an increase in the age they receive their pension.

It led Goldin to reflect on the growing division in wealth between the young and elderly, most obvious in disparities in home ownership. He added that older people spend on different products (medicines and hospitality, for example) compared to young people.

Technology will transform biomedicine and pharmaceuticals. It is also set to transform the energy system, mobility and manufacturing. It will get rid of many of the repetitive jobs that have always been the middle-run on a country’s growth trajectory.

“Where are the jobs going to come from when the machines do the repetitive jobs?” Goldin asked.

Because China’s workforce has already rapidly contracted, the economy has integrated technology and AI faster than others. Wages are growing and coupled with a 5 per cent growth rate, China is far from in crisis. Moreover, he predicted China’s debt and structural issues will improve.

Goldin said that the jobs of the future will be in cities. Although the knowledge economy is footloose and people can work anywhere, he predicted they will gravitate to diverse cities. Cities offer young people an ecosystem, and he expects to see dynamic cities pull away in terms of income and productivity growth.

In another trend he also flagged that people are increasingly less mobile – the cost of housing and transport means people will become less mobile. “There will be a disconnect between the people left behind and the people doing well – the people who see a future and those who don’t,” he warned.

Globalization has created an entangled system of goods, services and people flowing across national borders. The GFC was the first manifestation of how a highly connected system can lead to instability.

Goldin traced the rise of Trump in 2016 and Brexit, as well as support for populist and nationalist politicians to the dramatic loss of trust in government after the GFC. The pandemic was another manifestation of this “butterfly effect” where consequences ripple throughout the world. “Globalization spreads risks and opportunities,” he said

Goldin noted that the rise of populism is not apparent in Asia, where people still see the opportunity of globalization. “Globalization is alive and well and living in Asia. It’s just dead in the Atlantic,” he said.

He warned that “high walls” keep out skills and investment, and hinder coordination. Nationalism and protectionism make it harder for countries to manage risk and increase productivity.

He believes that the buoyant mood in Asia makes war in the region unlikely because it would be an act of self-harm. China has grown and benefited from globalization, but he noted that China is also fragile – incomes are still low and climate change requires huge investment.

In contrast, countries like the UAE are able to navigate climate change because they are wealthy. He described the UAE as the “new Switzerland” increasingly attracting people and investment in an unstable world. He pointed out how many Gulf states illustrate a business model where immigration works, showing how countries can be “a hive” for foreign workers.

Goldin’s positive future for China contrasted with his outlook for Russia. He said Russia’s dependency on fossil fuels at a time the world is moving to net zero, plus its aging population, will lead to long-term decline. He suggested a future where Russia joins the EU and becomes a breadbasket once Siberia thaws.

The past 20 years have seen large pools of capital become larger, more global and more diversified across asset classes. The Fiduciary Investors Symposium has heard how Bridgewater Associates is allocating capital and resources to meet this shifting paradigm and why investors can’t try to bet on certain geographic regions overperforming.

The past 20 years have seen large pools of capital become even larger, more global and more diversified across asset classes.

But at the same time, the world has become multipolar and liquidity cycles have become desynchronized.

Facing these challenges, the Fiduciary Investors Symposium in Oxford has heard how Bridgewater Associates is allocating capital and resources around the world.

The firm’s senior portfolio strategist, Atul Lele, told the symposium that these challenges have been presented by their long-term strategic partners to solve.

To achieve this, Bridgewater uses three questions to assess global asset allocation: how attractive the country’s assets are, which assets to buy and what currencies to hold and invest with.

“If you look at the secular growth outlook for any economy, it’s driven by two things, productivity and indebtedness,” Lele said.

“On a market cap weighted basis, the secular growth outlook has slowed quite materially when you think about where the US or Europe are.”

Lele said the past two decades have seen the global economy shift eastwards with a greater share of global output now coming from Asia.

“The share of global output that is driven out of Asia is roughly double what you see out of the US and Europe. The contribution to global growth is around six times,” Lele said.

“The Asian economic bloc is now highly interconnected through trade and capital flows. Asia’s largest trading partner is Asia.

“Even if you remove China, Asia ex China’s largest trading partner is Asia ex China. We now have a deeply interconnected trade and capital bloc. This speaks to the idea of having a very multipolar world relative to even 20 years ago.”

Hedging your bets

If investors are asking themselves whether being in every geography is worthwhile – and whether it was instead better to take bets on certain regions – Lele said the former is more important.

“If we look at most institutional portfolios they’re essentially betting on a continuation of US and to some degree European outperformance,” he said.

“They’re US and European-centric portfolios and we do think that geographic diversification is important in this multi-polar world.”

Lele noted this doesn’t mean there needs to be a rush for diversification for the sake of it, but portfolio managers need to be mindful of missing out on broader diversification.

“Where we are right now, it [the level of diversification] is low, as in investor allocations towards the US and Europe are so high and making this bet that you’re going to continue to see a unipolar world, when it’s very apparent you’re in this multipolar world,” Lele said.

With US President-elect Donald Trump winning a second term, investors are expected to face similar uncertainty as with his previous term. Lele said by taking Trump’s policies at their intent, it’s likely to be an inflationary environment rather than deflationary.

Trump had campaigned on placing tariffs on Chinese imports, potentially as high as 60 per cent, while he also promised to clamp down on undocumented immigrants.

“If we start to move up to the inflation limit which these tariff policies, these immigration policies will do then it starts to make it a less favourable environment for liquidity and therefore into assets,” Lele said.

“An environment which is likely going to accelerate a lot of the multipolar aspects that we see about the world.

“What the practically means is we’re in a trade war that’s expanded to a capital war and a tech war. We all hope it doesn’t escalate beyond that and hopefully it de-escalates into strategic competition as we saw between the US and Japan in the 1980s.

“But not only are we seeing the world that President Trump is articulating as being inflationary from purely a US perspective, but if you talk about the of reshoring it’s all very cap-ex intensive and that’s inflationary as well.”

Maintaining exceptionalism

As the largest global economy, Lele noted the US is currently 70 per cent of the global market cap for investors.

“That means to even maintain where it is, every marginal dollar that everyone in this room invests 70 cents of it needs to keep going into the US market and there’s going to be limits on flows and limits on discounting,” Lele said.

“If you look at what’s priced in for the S&P 500, it’s pricing in another decade of exceptional growth. It could happen but we’re going to be hitting some of the limits on the pro corporate side and on the flow side as well.”

Global markets have been dominated by US exceptionalism, but Lele said the big question is whether they will continue to maintain this status longer term.

“We’re asking ourselves what the limits are on it is because over the last 15 years you’ve seen the US outperform and if we look at the underlying performing it isn’t because it’s just a tech story,” Lele said.

“One third of it has actually been driven by the US tech and the sector composition of the US market but two thirds of it has actually been driven, within sectors, just US companies operating at a much better way than what you see around the world.”

Lele said the limits of US exceptionalism come down to how much further it can make gains in a pro-corporate environment.

“The last 40 years you’ve seen a pro-growth, pro-liquidity, disinflationary environment,” Lele said.

“Deregulation has been on a one-way street, de-unionisation has been on a one-way street, corporate taxes on a one-way street, interest rates being eased on a one-way street. There are limits to which those pro-corporate policies can continue. There are limits to how big the US can become as a share of market cap.”