Investors that focus on decarbonising their portfolios won’t change real world decarbonisation and would have more impact on climate change by buying transition investments.

In a recent report, The Policy Challenges of the Energy Transition, the investment team at £76.8 billion USS Investment Management which oversees the main pension scheme for the United Kingdom’s university and higher education sectors, together with Transition Risk Exeter, a commercial spin-out from Exeter University, argue that asset owners should focus most on collaborating and engaging at a macro level with governments and regulators to help to bring about policy change, rather than spend time on reducing portfolio emissions.

The easiest way for investors to reduce emissions from their portfolio investments is to sell high-emitting assets to other owners. But this does nothing to advance the low carbon transition or reduce the systemic risk of climate change that threatens all investors’ long-term returns, argues the report which endorses comments that USS chief investment officer Simon Pilcher shared with Top1000funds.com earlier in the year.

Moreover, emissions are a lagging indicator. In contrast, investment in renewables like solar and wind and clean technology where USS invests around £2 billion, is a leading indicator of the low carbon transition.

an urgent need for action

Climate change brings complex risks for investors. For example, it is non-linear in nature so a small increase in an underlying variable such as global temperature, or sea level, which changes gradually over time, can lead to a large increase in the probability of an extreme event, driving up risk.

“A fundamental mistake is to assume that any effect on the economy must be marginal, involving only small changes within the existing system, rather than recognising that it is system stability that is at stake,” states the report.

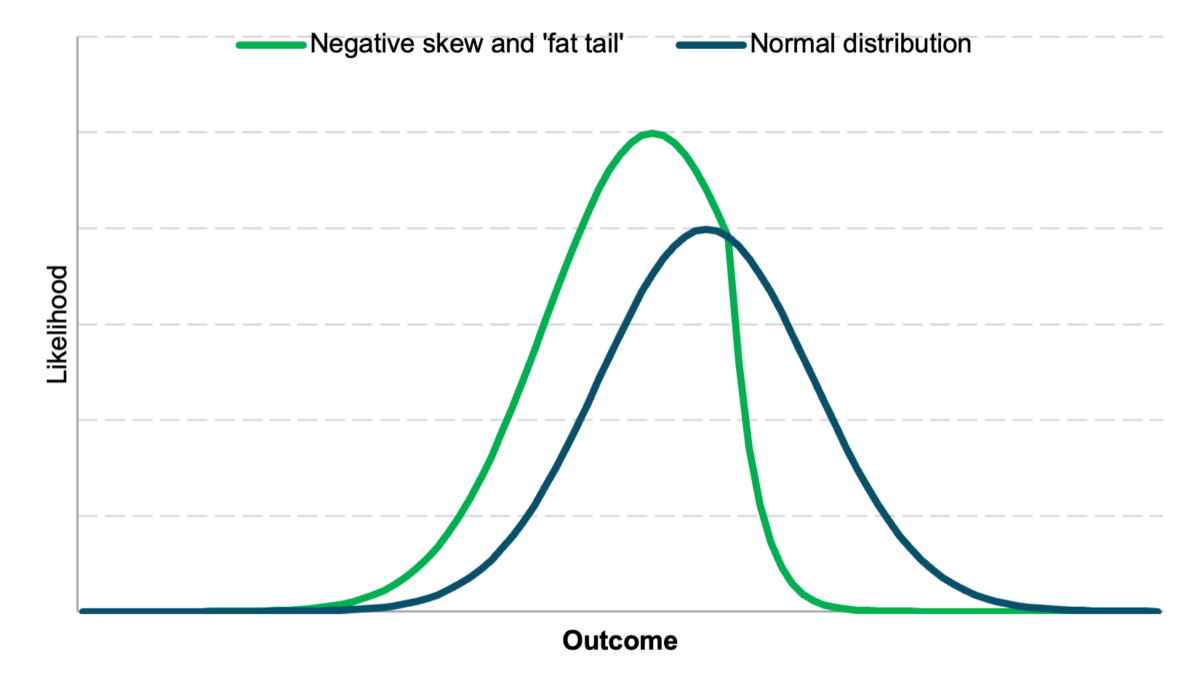

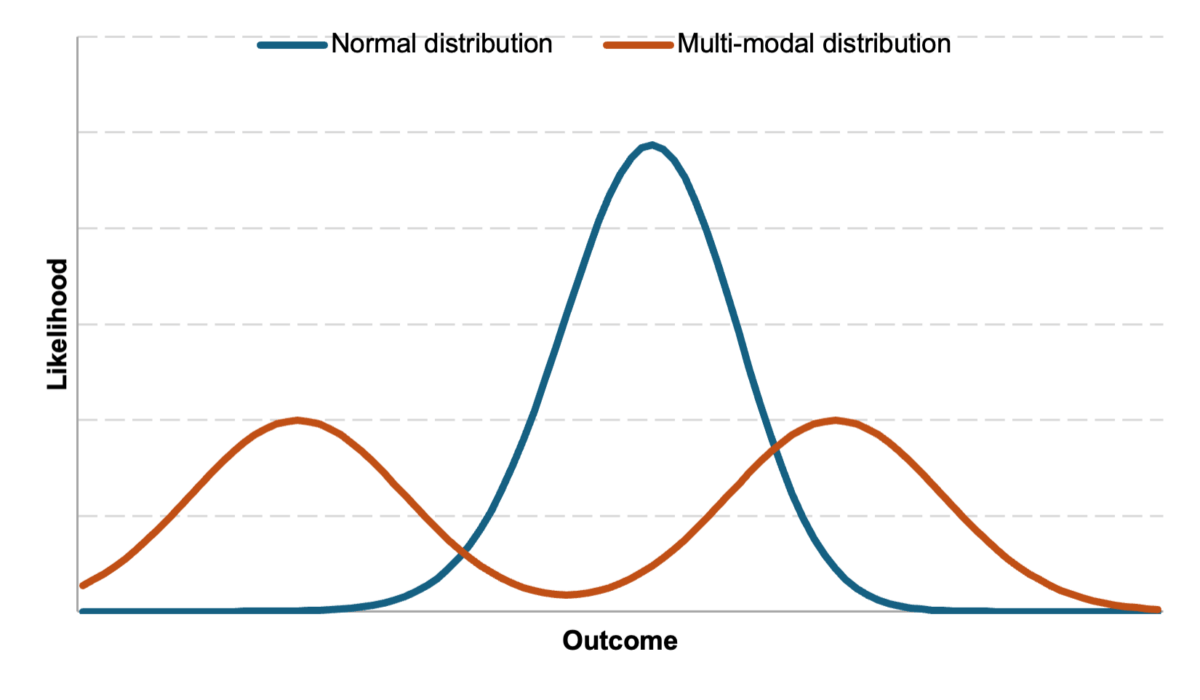

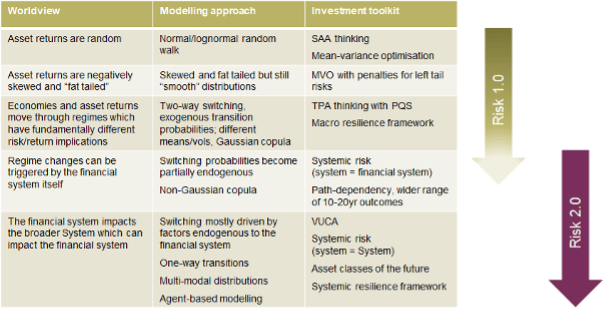

Nor do climate risks tend to have normal distributions: the likelihood of extreme impacts can be relatively high, or unknown, meaning that expected values often cannot be meaningfully calculated. Research by Norges Bank Investment Management similarly highlighted the challenge of reconciling the order of magnitude of climate risk exposures using top down vs. bottom-up approaches.

Instead, climate risk assessments should focus on identifying plausible worst-case outcomes for assets, supply chains, or regions of interest, and working backwards to assess their probabilities.

Government leadership

For the energy transition to continue and accelerate, governments must create the right conditions for clean technologies to replace fossil fuels.

“Only decisive action by governments can substantially reduce these risks and accelerate the growth of the clean energy economy,” states the report.

In the UK, this requires specific actions.

Early-stage policies should include support for research and development of new technologies, and measures such as targeted subsidies and public procurement to enable their first deployment.

In the middle stage of a transition, regulations can be even more powerful in driving the reallocation of investment on a large scale. For example, zero emission vehicles (ZEV) mandates have proven outstandingly effective in growing markets for electric vehicles in California, Canada and China. Yet in the UK, demand for electric cars is constrained by inadequate charging infrastructure and expensive upfront and insurance costs.

In the buildings sector, the ‘clean heat market mechanism’ is designed to shift investment from gas boilers to heat pumps, supported by heat pump subsidies. However, this effort is undermined by government levies.

In the late stage of a transition, a deeper restructuring of markets is often needed to make best use of the new technologies. For example, in the UK expensive gas sets the electricity price 98 per cent of the time, despite generating only 40 per cent of the power.

The authors argue that policy action to support the transition would bolster the UK economy, making the UK a more attractive market for global investment.

As a net importer of fossil fuels, the UK stands to benefit significantly while also boosting energy independence and security, which is itself of great value in the current geopolitical environment. “A fast transition to clean technologies could result in an estimated $12 trillion in savings globally by 2050.”

What is USSIM doing to respond

At USS, the reallocation of capital has already begun. In collaboration with the University of Exeter, USSIM has also pioneered a new approach to understand the risks and opportunities from the energy transition through scenario analysis.

This has involved modelling the macroeconomic and financial markets implications of different scenarios, in which alternative trajectories of the low carbon transition interact with pathways of global economic growth and recession.

USSIM uses this analysis to inform its strategic asset allocation, aiming for a resilient portfolio that is sufficiently robust to the various alternative future scenarios for the macroeconomic and investment landscape.

“We seek to assess our portfolio’s flexibility to handle boom-and-bust cycles, withstand market shocks, and seize opportunities as they arise.”

As set-out in USS’s latest Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) report, the investor has examined sector level patterns in outcomes across the various scenarios, and plans to use these to help to inform sector and possibly even company-level investment decisions.

Stranded assets

The macroeconomic effects of the transition are likely to vary substantially across countries.

Dynamic modelling of the global economy suggests that countries that are currently net importers of fossil fuels (including the UK) are best placed to gain in productivity, growth, and economy-wide employment. Those countries that are major exporters of fossil fuels are at greatest risk of negative effects of the transition. These risks are largely outside their control, depending not on national policy, but on changes in global demand for fossil fuels.

But the report also calls for better understanding of energy transition risks and opportunities driving into the macroeconomy; the sectors in which the transition to clean energy is taking place; and the assets or companies in which investments are held.

A recent analysis by Transition Risk Exeter in partnership with the UK Sustainable Investment and Finance Association (UKSIF) found that even with only policies that have already been announced being implemented and with governments’ existing emissions targets being met, over $2 trillion of oil and gas asset value could be lost as investor expectations are realigned with the reality of lower profits between now and 2040.

The UK is disproportionately exposed due to UK-based companies’ investments in overseas oil and gas assets.

The falling cost of renewable energy

Meanwhile the costs of the core technologies of the energy transition are falling rapidly. The cost of solar photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines and lithium-ion batteries fell by 78 per cent, 59 per cent and 82 per cent between 2013 and 2023, respectively.

These falls continue long-term trends: the cost of solar PV has fallen by a factor of ten thousand in the past 60 years. As clean technology costs fall, demand for them increases; investment follows demand and drives innovation; and costs fall further; thus creating a reinforcing feedback. The implication for investors is clear: assessment of risks and opportunities of the energy transition must be built on an expectation of non-linear change, and an understanding of its drivers.

Engagement pays

USSIM also engages with the companies in which it invests.

This stewardship-based approach to responsible investment is a complement, not an alternative, to integrating rigorous climate and transition risk assessments into investment decisions.

“We aim to help companies identify the right steps to take at each stage of the transition in their sector,” states the report.

USSIM also uses insights gained from the companies in which it invests to inform policy advocacy and how it collaborates with other investors .

“Strong government policy is essential to make faster progress towards a clean energy economy. The best available economic evidence points to a large net saving from this transition globally, as well as further gains being available from innovations in clean technology. We urge the government to double-down on its commitment, and act in all sectors to accelerate the growth of the zero-emission economy,” it concludes.