Elizabeth Fernando joined NEST as head of long-term investment strategy in November 2020. A year later she became deputy chief investment officer but is still very much focused on long term strategy.

“When I joined I went to lunch with Mark and he gave me a sticky paper with three things on it,” she says.

On that paper Mark Fawcett, the fund’s CIO, had outlined the areas he wanted Fernando to focus on: Think about how assets are allocated; how the internal asset allocation process works; and help with the development of the leadership team.

Now as Fernando talks to Top1000funds.com in a rare in-person interview at NEST’s Canary Wharf office, she says the fund is preparing to change how it allocates.

The change comes as it reviews its objectives – what it is actually trying to achieve – and how to allocate assets in line with that.

“Is a reference portfolio really the best way to do that?” Fernando says. “We’ve been working through that since I joined. It has involved looking clearly at what each asset is doing for us and whether it moves us closer to the objectives or not.”

Currently NEST is set up with three clear phases in the default fund: the foundation phase, the growth phase, and the retirement phase all of which have different investment implications.

“The foundation phase is when you first join at 22 years old and while we get them used to the idea of savings we keep volatility down. The growth phase is where members spend the vast majority of time, and then 10 years from retirement we gradually de-risk the portfolio to the at-retirement mix.”

Now, instead of having three “hard” phases the fund is looking to have a more dynamic portfolio, recognising that the needs of a 25-year old are not the same as a 50 year old.

“This will mean we will need to be more granular in how we meet those needs and take advantage of the fact we have now bigger asset size and so have more tools in the toolkit,” Fernando says.

One example is that younger members have longer time horizon and a different liquidity risk tolerance and that could mean a higher allocation to private equity, private credit and infrastructure.

“Towards the end of the year we will be talking more about a dynamic approach. The board have agreed to changing the objectives and we are working through the implementation plan now,” she says.

A more robust approach

NEST just celebrated its 10th birthday, making its first investment back in 2011. It’s first ever contribution was the odd amount of £19.65. the defined contribution fund represents the future of pension systems in the UK. One in three of the working population in the UK has a NEST account.

Employees can actively opt out but otherwise there is a mandate minimum contribution set by the government of 8 per cent made up of 3 per cent employer and 5 per cent individual contributions.

Assets now sit at around £25 billion and the fund is growing at around £400 million a month just due to contributions, not including investment returns.

It’s a good time to be reviewing the idea of the fund’s objective.

At the moment CPI plus 3 per cent after charges is the overarching objective.

“This gets you to a certain pot size at retirement. We think pensions are a bit more than that,” she says.

Other more mature defined contribution markets, such as Australia, are still grappling with the balance between accumulation and the best offering in the post-retirement phase that focuses on income.

“We have had defined benefit in this country for so long, simplistically when you say ‘pension’ to someone they think about a monthly cheque. People think they will hit retirement and automatically something happens, we know that is not the case and the sums are really difficult.”

This feeds into the idea of being more granular in what the fund is trying to achieve and while keeping the idea of investment phases, having softer edges around that.

“And if we have different objectives then what are the priorities of the different types of assets at different stages of the journey? For example the closer to retirement then there is more interest in the visibility of income and longevity so we have to make sure we’re finding the right assets to meet those requirements.”

Before joining NEST, Fernando spent nearly 25 years at the Universities Superannuation Scheme, and brought with her robust investment thinking around “making a case for investments”

“I bought with me some of the thinking about having a case for everything: why do it, why not do it, and the metrics to monitor whether we are on track or not. It helps with why you have the views you have and has driven recognition that some markets were priced for “as good as it gets” so we are bring positions back to neutral. It provides a framework for everyone to know why we are doing what we are doing, then we can have a discussion about why we are doing it and can filter out the noise. It makes things a bit more efficient.”

Changing investment allocations

NEST has started to bring its asset allocation back to a neutral position, having pushed out to an overweight position in risk assets in the autumn of 2020 when it took a view that the vaccine rollout would be a game changer for how markets would behave.

“It’s a really tough environment. We have a target of CPI+3 per cent after charges and when CPI is 1 or 2 per cent that was imminently achievable, but when CPI is north of 10 per cent it is very difficult,” Fernando says. “We think the world now is more difficult so we are bringing everything back towards neutral positioning.”

The only asset class that has delivered any real contribution to returns has been commodities in the past 12 months, she says.

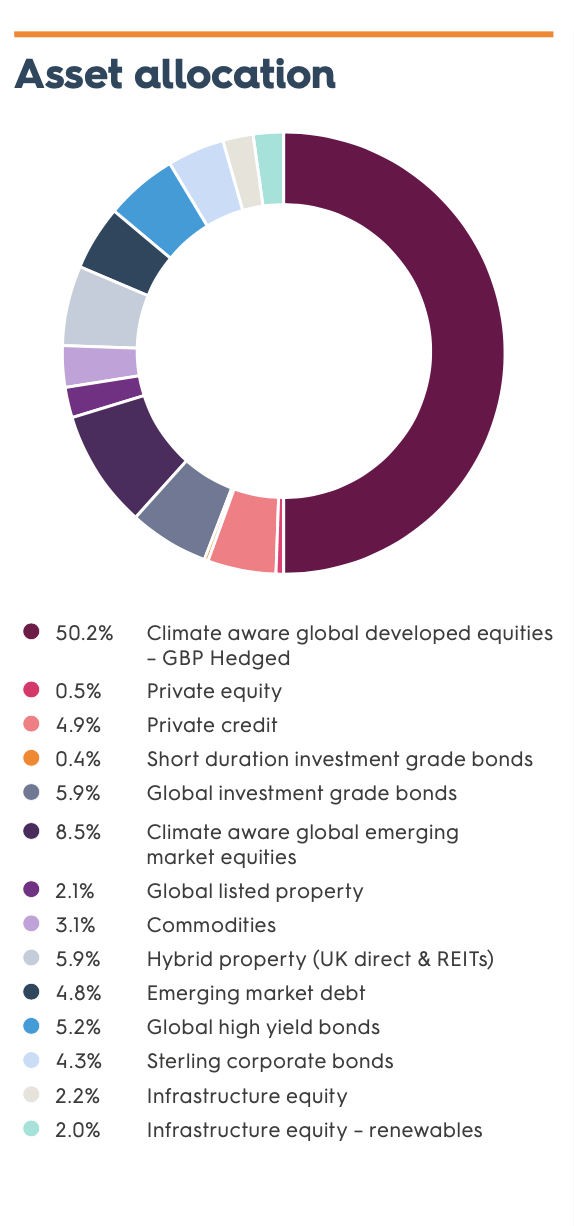

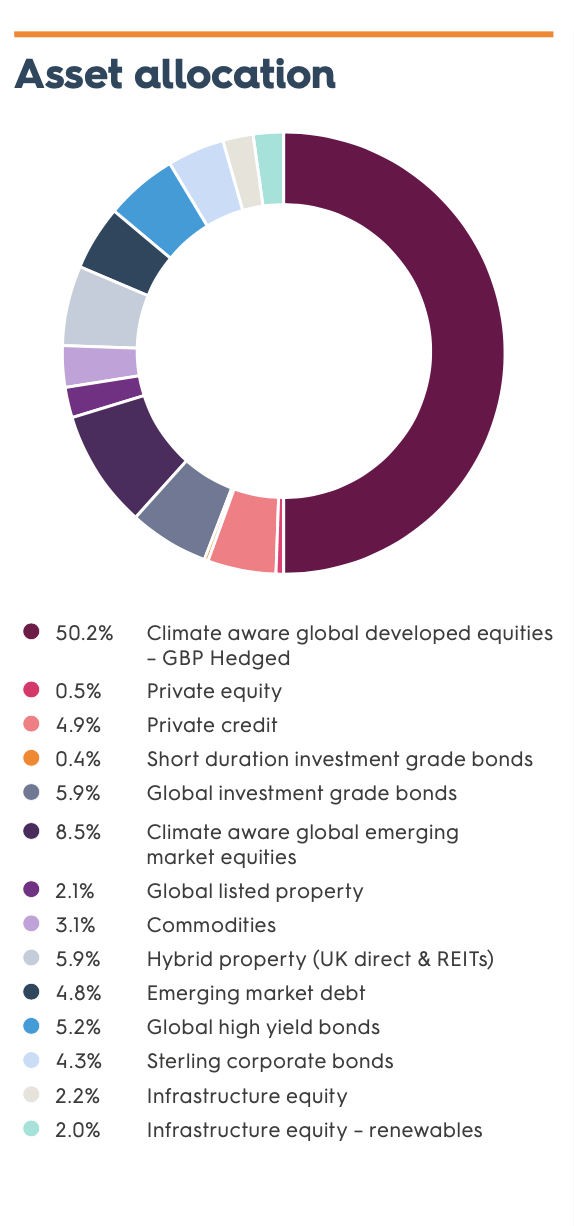

Globally, the star performer for many investors has been private equity, but NEST only began its foray into private equity two months ago and has a modest 0.5 per cent allocation. The aim is a target of 5 per cent of the portfolio invested in the asset class by the end of 2024. Looking ahead, that same 5 per cent allocation to private equity in 20 years – when NEST’s AUM could be around £250 billion – would amount to around £13 billion.

NEST is not to be under-estimated with its vocal quest to change the nature of private equity fees paid by asset owners being widely successful. It has had a massive impact on the future of private equity investing, essentially reinventing what investors pay for the asset class.

NEST now has two partnerships, with Schroders Capital and Harborvest, to source co-investment deals and is not paying any performance fees or carry.

“We proved it can be done,” says Fernando.

The growth of AUM is a key attraction for managers, she says, as is the reputational benefit of being a good manager of defined contribution assets in the UK given the growth potential.

“We had an initial target of 20 per cent to illiquid asset classes but we will have another look at that and how much we can afford to invest, our younger members can have a lot more than that.”

On the horizon

With the addition of private equity, and also recently infrastructure, Fernando says there are no other asset classes to add to the mix for now.

“We did have a bit of a look at natural capital. We’ve had climate tilting on a lot of the portfolios for some time, and that seems like a reasonable extension,” she says.

From a more immediate investment perspective NEST recently did a piece of research on different inflationary regimes and what that would mean for correlations and returns.

“And at what level inflation would become problematic,” she says.

It also looked at central bank digital currencies.

“I don’t think there is anything there right now, but we looked at it in the context of some of the challenges to the financial system in the longer term,” Fernando says. “We are trying to do that longer term thinking so where appropriate it gets incorporated into the asset class outlook.”

The team is also looking at the responsibility of investing members’ money in equities given the indexed nature of investments in that asset class.

“All of our equites are indexed so we are thinking about if in an index is a sufficiently high enough bar to allocate members’ money or should we be building the bar higher? Just because a company is in the index does that mean they deserve our members money?”

The focus on this “right” to manage members’ money is something engrained into the culture at NEST.

The investment team of around 40 has a more holistic, and outcomes-focused approach than a team that has internal investments, she says.

“We have people who have thought hard about pensions in the round and what good pension design looks like and how you organise yourself to deliver that,” she says. “We are all in it for the same outcome. We don’t have performance bonuses so no one is trying to maximise their personal income. We are properly in it together.”

NEST default strategy asset allocation as at June 2022