Investing outside Canada can bring important benefits to client portfolios, but the $73.3 billion pension fund for Ontario’s public sector workers, IMCO, also believes that this should be balanced by careful considerations including an overwhelming bias to developed markets – and staying mindful that forecasts of GDP growth rates are not a good enough reason alone to venture outside Canada.

So outlines president and CEO Bert Clark in a recent posting on LinkedIn where he describes a global investment environment characterised by higher geopolitical risk, deglobalisation and the growing importance of ESG.

Around 65 per cent of IMCO assets are invested outside Canada most of which is in developed markets (approximately 93 per cent) thereby avoiding heightened currency, ESG and geopolitical risk inherent in some jurisdictions leaving just 7 per cent of assets under management in emerging economies.

Clark argues that large Canadian pension funds significantly increased the amount they invested outside of Canada in recent decades, driven by the elimination of federal tax restrictions, and the belief that large parts of the world were converging towards free markets and democracy. Tectonic shifts like the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, China joining the WTO and economic and monetary union in Europe signposted the way.

“In retrospect, it is hard to believe that so much progress occurred in such a short period of time. The sad postscript to the era that was thought to be the end of history is well known to us today. In recent years, globalization has waned, and geopolitical tensions and risk have risen,” he argues pointing to Brexit, US tariffs on Chinese exports and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as examples.

In today’s context, he argues Canadian investors need to have a well-considered approach to where and why they are pursuing geographic diversification. A quick return to the optimistic years at the turn of the millennium seems unlikely today.

The need to invest outside Canada

Still, the benefits of investing outside Canada are compelling. Particularly because of the relatively small size and concentration of Canadian capital markets. The total market capitalization of the MSCI All-Country World Index (MSCI ACWI) is US$82 trillion while the market capitalization of the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) is only about 3 per cent of that of MSCI ACWI.

Meanwhile, financials and energy account for approximately 50 per cent of the S&P TSX index. The 10 largest companies in the TSX represent more than 35 per cent of the index but the top 10 companies in MSCI ACWI (which include behemoths like Apple and Microsoft) represent only 18 per cent of that index.

“An investor that only invests in Canadian public equity is investing in a very narrow subset of global equities, with a high concentration in financials and energy and a high concentration in a small number of companies,” he explains.

In addition, some important public debt market investment opportunities in Canada have been getting smaller.

One of the most important advantages of geographic diversification is the access it provides to private assets. For example, the nine largest Canadian pensions have reported investments of over $400-billion in private equity and $100-billion in private credit. The Canadian private equity and credit opportunity set simply would not have accommodated this level of investment. The Canadian government still owns assets like airports, ports, power utilities, roads and bridges that Canadian investors have been able to snap up overseas because of privatization programmes in other jurisdictions.

Clark warns that the correlation between economic growth and equity market returns is not strong enough to be the sole driver of investment decisions – especially in emerging markets. For example, from 2003-2021, Chinese GDP grew at an annualized rate of 8.55 per cent vs. 1.95 per cent in the US, but equity market price returns (based on MSCI indices) in the two countries were essentially the same over that period.

“Higher GDP growth did not result in higher equity returns.”

Many factors other than GDP growth drive equity market returns, including relative central bank policy, valuations, tax policy, competition policy, foreign investment and currency restrictions, the size and efficiency of domestic pools of capital, location of revenue source, international tax treaties, labour policy, geopolitical risk and ESG considerations.

Where to invest?

In answering the question where to invest outside Canada, investors should consider whether they have any real advantage investing in the jurisdictions they are contemplating.

Real investment advantages include things like operational leverage (the ability to leverage centralized risk, legal, HR, IT, back and middle office capabilities), relevant sectoral expertise, the ability to leverage scale (by making large commitments to best-in-class partners to reduce fees, for example) and the ability to invest directly and effectively oversee investments in the geographies being contemplated.

Just as only a very few companies can operate effectively in many jurisdictions, most investors can only leverage real investment advantages in select geographies.

Not having the ability to leverage any real advantage in a geography doesn’t mean it should be entirely excluded from an investor’s portfolio. But, because the opportunities for outperformance are less, it should mean investing less in those places and more in jurisdictions where they can leverage their advantages.

“This is why IMCO tends to focus its investments outside Canada in select jurisdictions, including the US, Europe and Australia. These are places where we are able to leverage our investment advantages, particularly our ability to partner with best-in-class investors, invest directly alongside our partners in private assets and participate in energy transition investments,” he says.

Investors should also be mindful of the impacts of foreign currency movements because these can have material impacts on investment risks and returns. Longer term foreign currency losses can sometimes be material (the Argentine Peso has declined by 97 per cent vs. the USD over the past 10 years) and in the near-term, movements in exchange rates can create material investment gains and losses that need to be planned for.

Near-term currency gains and losses for most developed market currencies can be efficiently mitigated through straightforward currency hedging transactions. But, emerging market currencies are more difficult to efficiently hedge.

Even in jurisdictions where hedging is more feasible, hedging currency requires access to liquidity to post as collateral. Investors who invest in foreign markets and hedge the related currencies will need to consider the liquidity requirements of doing so, which may mean owning more liquid low return assets like government bonds.

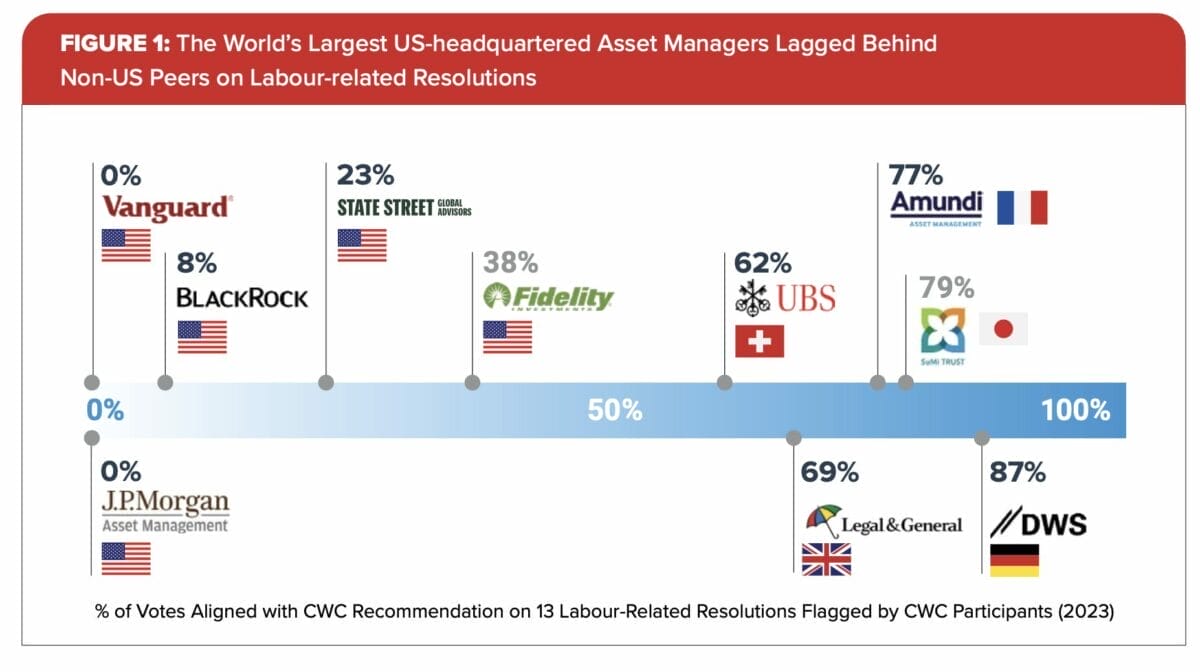

Today, investors who pursue geographic diversification also need to consider their ability to do so in a way that is consistent with their ESG beliefs. In some countries, particularly in frontier and emerging Markets, the laws and practices relating to environmental, labour, corporate disclosure, corruption and corporate governance make that more difficult.

Investors also need to consider the political risks associated with investing in some countries.

For example, Clark says the geopolitical risks associated with investing in some countries like Russia and China are much higher today than they have been in recent decades. Investors need to consider whether these geopolitical risks are ones they are willing to accept and are adequately compensated to take.

“IMCO does not invest in Russia and restricts investments in China almost exclusively to public equities and to a very small percentage (2 per cent) of the total assets we manage,” he concludes.